![]()

The Words of the Ward Family

|

|

The Words of the Ward Family |

Thomas Ward is Dean of the International College and Vice President for International Programs at the University of Bridgeport.

On May 4, 1970 National Guard troops shot into a crowded student demonstration at Kent State University in Ohio killing four students and wounding nine others. In the days following the Kent State shootings, American universities were ablaze in protest and rage. Sit-ins consumed my university campus and led to the canceling of classes. I recall attending a demonstration in the main quad of our campus where we students heard an endless line of speakers denounce the government of Richard Nixon. Unexpectedly, in the midst of this, a man in his fifties made his way to the stage. With a thick Eastern European accent, he warned the students of the dangers of communism and shared about his personal experience of the 1956 Soviet crackdown in his homeland of Hungary. He was not received well by me or by most other students. For us, the War in Vietnam had nothing to do with what had happened in Hungary.

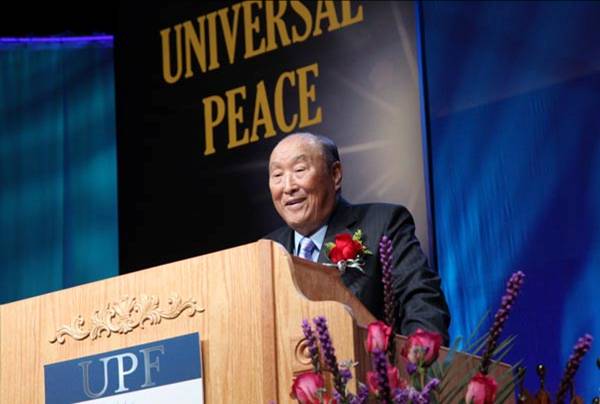

When I was introduced to the work of the Reverend Dr. Sun Myung Moon less than a year later, the greatest challenge that I faced was accepting its uncompromising opposition to communism. I suspected that Reverend Moon's rationale for opposing communism stemmed from his experience in his home country of Korea, which made me think of the gentleman who had spoken about Hungary on that day in May in 1970.

For me, the atrocities perpetrated by Stalin, Mao, Castro, and Khrushchev may have been done in the name of communism but they were an abuse of the Marxist ideal. What reinforced my sympathy for Marxism was a conviction that the alternative, i.e., American style capitalism, was no better. US imperialism had resulted in egregious human rights violations by the pro US governments of the Dominican Republic's dictator Rafael Molino Trujillo, Haiti's "Papa Doc" Duvalier, and the racist ruling oligarchy of South Africa. From an ideological perspective, I could argue that, for communism, dictatorship was a step in a systematic process and was only justified in the transition period from socialism to communism. On the other hand, "imperialist client states" institutionalized repression indefinitely, based on a suspect apologetic that there existed "threats" to National Security.

In late March, 1972 Reverend Moon visited Paris, France and a group of the early members were afforded an opportunity to spend three days with him. On the occasion of that visit, Reverend Moon entered into a conversation that detailed his reservations about communism. I anticipated hearing more of what I had heard in my college days but, unlike many of the critics whom I had heard in the past, Reverend Moon did not engage in ad hominem attacks to justify his opposition to Marxism. Instead his exposé focused on the inherent flaws in the core underpinning of the Marxist ideology -- the materialist dialectic. His lecture demonstrated that the Marxist dialectic was intrinsically flawed, based on its misunderstanding or its misrepresentation of natural processes.

Reverend Moon introduced a corrected dialectical paradigm, demonstrating that the basis for progress within nature was not Frederick Engels' struggle of opposites but the unity and cooperation of complementary pairs: positive and negative valences in the case of atomic and molecular structures; stamen and pistil in plants; males and females in the animal kingdom; and men and women in the case of humankind. Reverend Moon pointed out that, in nature, pairs thrived on harmonious interaction rather than on permanent conflict or division, as Marxism had posited through its emphasis on the primacy of struggle over unity in the Marxist dialectic (unity and struggle of opposites) of relationships.

For me Reverend Moon's critique was simple yet stunning and disarming. My attitude toward Marxism changed. I came to realize that no matter how sincere and sacrificial Marxists might be they could never effect genuine social change because their ideological paradigm was inconsistent with natural processes.

It was not only his critique of communism that impressed me about Reverend Moon. It was his attitude toward communists. Reverend Moon did not question their idealism. He did not depersonalize them and mentally cast them out of the human family. He went the path of Jacob, not the path of Abel. The Elder Brother Cain killed his younger sibling Abel because Cain did not feel loved and elevated by Abel. He felt marginalized and rejected by God.

Later in biblical history, a younger sibling Jacob, like Abel, succeeded where Abel had failed. He set his mind on sharing the blessing he had received with his elder brother. Indeed, he understood that his Blessing was not only for him and that it lost its meaning without his brother. He grew to long for his suffering elder brother Esau. Through offering many of his possessions to Esau, he won his brother's forgiveness and love. The two could melt their differences in a tearful reunion and God could embrace both of them. Jacob prepared himself for twenty-one years to meet and reconcile with his lost brother Esau. Reverend Moon prepared himself from October 1950 when he was freed from prison in North Korea until November 1991 when he could meet and embrace his captor Kim Il Sung in Pyongyang, North Korea and they could declare publicly (before God) that they were reconciled brothers.

History, I believe, will acknowledge that the Reverend Dr. Sun Myung Moon did more than develop a penetrating critique and counter proposal to Marxism. The organizations that he founded and the panoply of activities pursued through these organizations played a pivotal role in ending the Cold War. This began when Reverend Moon, with the collaboration of Dr. Sang Hun Lee, formalized his comprehensive analysis of Marxist-Leninist ideology. Reverend Moon devoted special attention to the practical implications of Marxism-Leninism's militantly atheistic position. In 1968 this led to the founding of the International Federation for Victory over Communism (IFVOC) in Korea. That organization's membership reached over 4 million in Korea. By 1970 Reverend Moon had set up training centers on his critique and counter proposal to communism in various parts of his homeland. These centers conducted three and four-day programs explaining and critiquing communism for literally hundreds of thousands of Korean college students, teachers, army officers, police officers and civic leaders. In the late 1960's Reverend Moon's work in this area also spread to Japan where it focused on College campuses and had very significant success in that country.

When Reverend Moon began his ministry in the United States in 1971, many American youth were caught in a morass of moral and ideological confusion. Reverend Moon began his ministry by attempting to address America's identity and mission. In his public speeches in locales such as Madison Square Garden and Yankee Stadium, Reverend Moon passionately described the sacrificial course of America's Pilgrim Fathers, explaining to his listening audiences that these early settlers had abandoned the comfort and familiar surroundings of their homeland in order to have a place to worship their God and exercise their faith. He recounted how during their first winter in the New World, Pilgrim elders chose not to eat the grain stored in the hull of their ship because it was for the first spring planting and thus they perished from hunger and disease.

Reverend Moon was not ignorant of America's transgressions, e.g., of how white settlers had abused both Native Americans and Africans. But as a religious man, he felt that God could forgive America's serious transgressions because, at its founding, there existed a critical mass of men and women of faith. Even when he faced imprisonment in America, Reverend Moon reflected on the motivation and heart of the first settlers at Plymouth. He felt that he should be ready to go to prison to prevent that precious foundation from being lost. In his sermons and public talks, he called upon Americans to emulate the quality of faith demonstrated by the Pilgrim Fathers. He shared this appeal for a renewal of faith with the members of his Church and with public audiences in all fifty states during the first three years of his ministry in America.

In 1981 Reverend Moon became the first foreigner in United States history to be indicted for alleged irregularities in the very first Income Tax Statement he had ever submitted to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Reverend Moon, who had provided hundreds of millions of dollars by then for education, the media, and humanitarian projects in the United States, was indicted for allegedly participating in a conspiracy to evade payment of $7,300 in income taxes over a three-year period. To indict Reverend Moon, US Senator Orrin Hatch pointed out that the US Department of Justice had violated its own guidelines on what constituted a federal offense and Senator Hatch was very critical of what had happened to Reverend Moon.

Nevertheless, at the age of sixty-four, Reverend Moon willingly began to serve an eighteen-month prison sentence in a federal corrections institution in Danbury, Connecticut. I say "willingly" here because, when indicted in July 1981, Reverend Moon was in Korea. No extradition treaty existed at that time between Korea and the United States. Nevertheless, Reverend Moon chose to return to the United States to face prison. This would at least allow him to remain in America after serving his sentence and thus continue the mission that he felt that God had given

I spent the entire day of July 20, 1984 with Reverend Moon beginning with breakfast time. He spent the day comforting and uplifting those of us who were depressed and embarrassed by what the United States had allowed to happen. Just prior to leaving for prison in the evening, he met with a group of a hundred or so of us to reassure that "something good" was going to result from his time in Danbury.

Reverend Moon felt appreciative of the support that he received from many ministers and large Church organizations such as the National Council of Churches and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference that protested his sentence. However, he asked those who expressed concern to look beyond his personal circumstance and even beyond the whittling away of religious freedom in America. Due to its militant atheism, Reverend Moon maintained that communism constituted a more serious and imminent threat to religious freedom than what he faced in the United States. By attending a seminar on this topic through an organization that he founded, known as CAUSA International, he maintained that American ministers could see more clearly why communism's continued expansion should concern religious leaders. Between 1984 and 1986 more than 70,000 ministers responded to Reverend Moon's request and attended CAUSA seminars. This led to many of these ministers also inviting their state legislators and congressmen to attend such programs.

Perhaps even more important than CAUSA was Reverend Moon's decision to create the Washington Times. Reverend Moon created this newspaper for America while he faced prosecution at the hands of the US government. Its stories on topics such as the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) and the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan helped to change the world's political landscape. In November 1987, The Washington Times ignited a nationwide controversy that resulted in the White House reversing its plans to have Mikhail Gorbachev be the first communist leader invited to address a joint session of Congress. The Washington Times' breaking of this story beginning on November 13, 1987 and headlined on November 17 reminded readers of Gorbachev's continued support of the presence of Soviet troops in Afghanistan. The coverage generated such concern that it led the White House and the congressional supporters of the invitation to backpedal. They rescinded the invitation to President Gorbachev on November 22. Four months later, President Gorbachev announced that Soviet troops would be withdrawn from Afghanistan.

On July 1, 1973 Reverend Moon began what he described as the "March to Moscow: Three years later on October 4, 1976 at a Church celebration, Reverend Moon reiterated his determination to have a religious rally in Moscow and that seemed unthinkable in those days. At that same time Reverend Moon also announced plans to create a daily newspaper in New York and News World began to print in December 1976. The News World was followed soon after by Reverend Moon inaugurating the World Media Conference (1977). At Reverend Moon's request, the World Media Conference began to conduct fact-finding tours to the Soviet Union for journalists in 1982. This initiative was begun by Reverend Moon during his court case.

Initially, the reception of these journalists in the Soviet Union was quite cool but after the Washington Times marshaled forces to block President Gorbachev's address to a joint session of Congress, officials from the Soviet press agency Novosti visited the Times editorial offices in December 1987. These discussions led to the World Media Association being invited to co-sponsor a Conference with Novosti in Moscow in 1990. Through that Conference it finally became possible for Reverend Moon to realize his dream of hosting a rally in Moscow. While there, he met with and began a working friendship with the Gorbachevs. The American journalist Georgie Anne Geyer was stunned to observe such developments and she wrote an article commenting on the April 1990 Moscow Novosti-World Media Conference program. Ms. Geyer commented as follows:

Of all the impossible events that have occurred in the Soviet Union in the last five years, probably none has been as unlikely as the happy meeting in recent days between Mikhail Gorbachev and the Reverend Sun Myung Moon.

The Moscow News called Reverend Moon "the most brilliant anticommunist and the No. 1 enemy of the state" -- and then added, please, that it was 'time to reconcile:

The encounter led to the Soviet government supporting an effort by Reverend Moon to sponsor a visit to the United States by Soviet legislators where they participated in an educational conference sponsored by Reverend Moon. In December of 1990 and in February of 1991, Reverend Moon sponsored conferences for more than one hundred Soviet legislators. Some 3000 Soviet young people were also sponsored by Reverend Moon. They visited the United States and participated in an exchange program under the auspices of the International Educational Foundation (IEF), an organization founded by Reverend Moon to promote education, reconciliation, and dialogue amongst the young people of the free and the communist worlds. Numerous Soviet students also received scholarships to study at the University of Bridgeport.

In April 1988 Yu Kikimura, an operative of the Japanese Red Army (JRA) -- an organization with established ties to North Korea -- was arrested on the New Jersey Turnpike for arms possession and was detained. At the time of his apprehension, the FBI confiscated Kikimura's weapons and his notebook that specified his targets in America. Reverend Moon was informed by the FBI that he figured prominently on the list.

In spite of this, Reverend Moon never forgot his commitment to reconcile with those who had persecuted, imprisoned and tortured him in North Korea from September 1947 to October 1950.

At the time of his 1990 visit to Russia, he began his outreach to North Korea. In 1990 Soviet journalists joined a World Media Conference fact-finding tour that visited South Korea. During their stay in Seoul, the Soviet journalists met with Reverend Moon and he requested that they visit Pyongyang on his behalf. He asked that they kindly tell the North Koreans that "Reverend Moon is not your enemy," and that he wished to visit the land of his birth and to meet with North Korean President Kim II Sung. The journalists complied with this request and traveled to North Korea on Reverend Moon's behalf.

Unexpectedly in late 1991 Reverend Moon received an official invitation to Pyongyang in November 1991. While there, he shared his religious views with them. Reverend Moon's kind but direct approach shocked both Kim Il Sung's followers and Reverend Moon's followers in attendance. Over the protest of some of his subordinates, Kim II Sung decided to meet with Reverend Moon on the last full day of his visit to the North. Reverend Moon embraced his captor Kim II Sung and walked with him hand-in-hand. Reverend Moon comforted Kim Il Sung, lest he found unease or guilt, telling him not to worry because "blood is thicker than water" and he treated Kim II Sung as if he were his lost elder brother. Reverend Moon, once seen as a hated enemy of the North, was soon to be officially recognized by the DPRK (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) as a Korean Hero for Unification.

This encounter proved to be highly positive. With the assistance of Reverend Moon's Summit Council for World Peace, high-level meetings on Korean reunification took place in 1992 at the United Nations and in Washington, D.C. These meetings brought together top officials of the U.S. Department of State and the Foreign Ministry of the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea. As a follow-up to these efforts, Reverend Moon sponsored a good will delegation of 40 former high-ranking U.S. officials to Pyongyang.

Congressman Ichord, who headed the delegation, met with President Bush's National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft prior to the visit and briefed President Bush after the visit. Ichord brought a communiqué from the White House with him. He presented this to DPRK foreign policy architect Kim Young Sun upon his arrival at the airport in Pyongyang. The delegation met with high-ranking Party officials while in the North and President Kim II Sung himself spent more than three hours with this group and hosted the delegation at a luncheon.

Congressman Ichord requested that I remain in Pyongyang at the conclusion of the AFC visit. I spent five additional days there, especially trying to craft a statement that reflected the concerns of both the members of our delegation and those of the DPRK's officials whom we had met. Although I was informed that the DPRK foreign ministry officials "liked" my statement, no government decision was taken during my stay there. Prior to my departure from Pyongyang, on June 6, 1992, I was assured by DPRK officials that "they would do something:'

On June 23, 1992, I received a telephone call in my New York office from a North Korean diplomat at the United Nations requesting a meeting with Congressman Ichord, lobbyist Gary Jarmin, one retired foreign service officer and myself. In our meeting in a restaurant on New York's upper East Side, the DPRK official informed us that, as a gesture of appreciation for our visit to Pyongyang, the DPRK had made a unilateral decision to cancel its annual month of anti- American demonstrations, which extended from June 25th (date of the start of the Korean Conflict in 1950) to July 27th (date of the truce ending the conflict in 1953).

The DPRK official asked Congressman Ichord to convey this directly to the Bush administration, which he did on June 24, 1992, both by telephone and by facsimile. He explained that his reason for asking the Congressman to convey this rather than going through normal channels was because he wanted Reverend Moon to be credited for this work. The DPRK anti-American demonstration month has not resumed since that time and Reverend Moon has encouraged direct engagement between the United States and Pyongyang.

What motivates Reverend Moon? Among the anecdotes that Reverend Moon has shared, there is one that has struck me more than any other. While Reverend Moon was a prisoner in North Korea, he and his fellow detainees never had adequate or sufficient food to eat. When relatives visited the prison camp, they often brought food. It was not unusual to conceal such food from fellow prisoners. However, Reverend Moon always shared his, including the most precious gift of all which was a rice powder used to make rice cakes. Most prisoners did little more than thank Reverend Moon when they received rice powder, but there was one noted exception:

And out of all those people, one, after eating a portion of it, would save a tiny bit, put a tiny amount aside. And when that had accumulated to this much, he remembered my birthday; and on that day, he did something with the powder. He made a dough out of it, molded it like a cake or pudding, and celebrated my birthday right there in the dungeon.

I can never forget this person; I want to meet him in my lifetime. I am going to repay him. When I remember him doing such a thing for me, I repent, I feel regret, and say to myself, "Why did I not give him more? He was doing this for me, even though he did not have enough out of that small portion I gave him. Why did I not give him more?" I always recollect that scene.

For me this anecdote provides remarkable insight into the life and work of Reverend Moon whom I have been privileged to know for almost forty years. What kind of person would repent for not giving more to the one person who was kind enough to remember his birthday? I believe that this passage shows that already, more than five decades ago, Reverend Moon had grown accustomed to doing good, regardless of whether or not it was recognized. One of Reverend Moon's life motto is "Give and forget that you have given." Those who know him well understand that this is more than a motto; it is his way of life.