![]()

The Words of the Flinn Family

|

|

The Words of the Flinn Family |

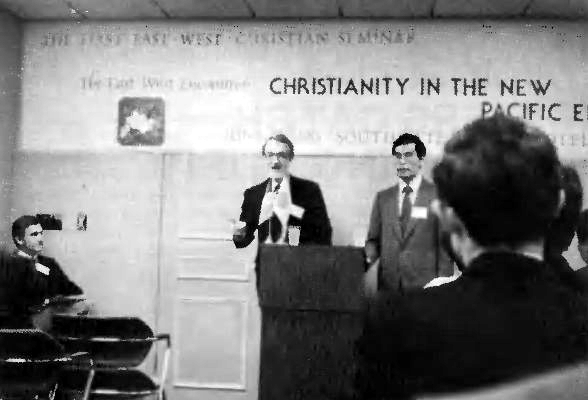

Dr.

Frank Flinn delivers his speech, translated by Dr. Tadaaki Shimmyo.

This "excerpt" is an edited combination of the speech Dr. Flinn wrote for this occasion and the speech he actually gave in which he simplified the contents for the sake of easier translation.

A number of years ago when I was living in Santa Fe, New Mexico, I studied the Tewa Indian language from a learned woman there. On one occasion when I was with my teacher, a group of Japanese businessmen visited her and the place where the Pueblo Indians live. I was struck by the kinship between the Japanese and the Indians. They have many things in common -- rites of purification, mountain dwellings of the gods, an appreciation of the shimmering sacredness of nature in mountains, trees, and flowers; even their languages are similar. Of course, this is no accident. Archeological evidence confirms that both the Japanese and the American Indians have their origins in Upper Mongolia. The most striking similarity between them, however, is that neither of these peoples have what can be called creation stories. Rather, both have what are properly titled "emergence myths."

What is the difference between a creation story and an emergence myth? The Biblical account of the creation is a typical creation story. Here, God creates all things, and is distinct from all He has made: in the words of Karl Barth, God is "wholly other." Stories about the primal emergence are fundamentally different.

Here, deities are considered to be the ancestors of the human race, or of a portion of it. The incarnation of God, as it were, happens with the creation and is not a subsequent event in history, as it is in Christianity. Thus, in Japan the sun goddess has traditionally been considered the ancestress of the Imperial household itself.

The differing ramifications of the emergence myths and the creation stories manifest themselves in important ways in the cultures that espouse them. In the cultures based upon emergence stories, there is a continuity between the divine and the human. The kingdom of nature is not something to be mastered or dominated. Nature, culture, religion, and the political order are intimately related.

On the other hand, cultures centering upon religions that have creation stories, when they become secularized, tend to develop a radical distinction between the sacred and the profane, worship and work (what I call the "Sunday to God, the week to the Devil" phenomenon), and between church and state.

The ethic that develops out of the theology of creation stories is what I call an ethic of honesty. As Martin Luther says, "Let God be God so that man can be man." So long as "creation" cultures remain God-centered, the ethic of honesty remains a very powerful and creative force within the society. The way Americans are honest is illustrated in the way we walk up and shake somebody's hand and say, "Hi! My name is Frank. What's yours?" It's a kind of openness, forthrightness, and informality.

As one reviews the successive stages of secularization that Western society has passed through, one is awed by the ethic of honesty which has led to the self- critique of Western institutions by Western thinkers themselves. So long as Western Christian culture maintains God centeredness, the ethic of honesty works to our advantage. But in fact, especially since the time of Machiavelli and Bacon and so on, Western society has become less and less God-centered and more and more human-centered. Honesty has turned into skepticism, and skepticism into cynicism.

In contrast, cultures that are based upon a theology of emergence do not develop a radical separation between the divine and the human, the sacred and the profane, the church and the state. The central ethic that emergence theologies give rise to is one of loyalty. Japan, in my estimation, stands at the forefront of "emergence" cultures. Although Japan, like the West, has undergone a modernization process, this process has been mediated by an ethic of loyalty which has kept the sacred and the profane in close relation to each other.

I spent the last year reading business codes for Japanese firms that make automobiles and videos and all kinds of things that one would expect to see in a very materialistic society. I was amazed to find that these codes outlined spiritual values as the basis for how the businesses should be run. Some Western commentators have said this is the way the Japanese employers trick their laborers into working harder so that they can increase production and profit. I don't believe these Western commentaries, because I know they are coming out of an ethic of honesty that has been turned into cynicism.

What I have put before you are two ethics: one is the ethic of honesty -- good in its beginning, but which has become very cynical -- and on the other hand an ethic of loyalty which I think pervades the Far East much more so than the West. Although the ethic of honesty has evolved into something rather destructive, in its original form it has many fine features. The ethic of honesty is what I believe built America in its formative years, when the country was will God- centered. (I might add that from the days of its founding onward, America was much less influenced by cynicism than Europe.) The ethic of honesty led to the conviction that each person is responsible for his or her action, that each individual counts, that each person should have a vote, and that one should deal fairly with others. But in this century, particularly in the United States, the ethic of honesty has degenerated into what Dr. Richard Rubenstein calls "self-aggrandizing egoism." I have become more important than my family, my state, my church, and even my God. The ethic of honesty in the West stands in great need of being tempered by the ethic of loyalty.

Yet there has been a fundamental wall of miscommunication between the two ethics. Pearl Harbor and Hiroshima are symbols of that wall. To Americans, Pearl Harbor was an act of dishonest treachery. The Japanese appeared to be negotiating in Washington, but while they were doing that they attacked Pearl Harbor. The Americans never really understood the Japanese. Americans viewed the kamikaze pilots as nothing but collectivized fanatics, chiefly because Americans could not envision the extent of self-sacrifice involved in an ethic of loyalty. Although Americans were sacrificing their lives in the war, the use of outright suicide was inconceivable to them. On the other hand, the United States has been blind to its own defects. At Pearl Harbor, the Japanese attacked only military targets; not one bomb was dropped on the city. In warfare, that's moral. By contrast, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on the center of the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Many people are asking nowadays why Japan is overtaking America economically. It is my opinion that Japan is overtaking the United States because this very ethic of loyalty pervades its society. This ethic does not separate the sacred from the profane, it does not cut the Kingdom of Heaven off from the kingdom of the earth; it preserves sacredness in many of the ordinary things of life. It is this ethic of loyalty, which goes back to the wellsprings of Japanese tradition, that allows Japan to succeed today.

Many American firms are now reassessing the ethic of loyalty. After so many years of increasing secularization in American society, there is now a counterweight movement to bring the sacred and the profane back into some kind of coordination. It's interesting that the firms that either already possessed or are now adopting spiritual codes similar to those found in Japanese corporations are the ones that are succeeding.

At the same time, those who come from a tradition of loyalty perhaps need to learn the virtues of the ethic of honesty; especially its emphasis upon openness and forthrightness in communication. The Japanese expert Hajime Karatsu noted the lack of forthright communication with American firms on the part of the Japanese government as one factor in the current Japanese-American impasse.

What do these two ethics have to do with one another today? Can the impasse be breached? Do we have a day of despair before us or a day of hope?

I'm not a prophet, but I find it very interesting that already at the turn of this century the America philosopher Josiah Royce turned to Japan in order to study the philosophy of loyalty. Royce saw in the Japanese Buddhist ethic of Bushido a corrective to excessive American individualism, which he already saw developing in 1900. Royce believed that the key to the future of humankind lay in loyalty to what he called "the beloved community," which was his translation of St. Paul's term, "ecclesia." Membership in this community demands both an ethic of honesty and an ethic of loyalty, in right relationship to one another. The fusion of these two ethics Royce called "critical loyalty," which he saw exemplified by Paul of Tarsus.

Royce saw that loyalty to the universal beloved community can operate on three levels. The first level is the small or limited community level, the second is the regional or provincial level, and the third is the international or universal level. It is my conviction that Royce has an ethical, moral, spiritual message both for Japan and the United States today. Japan, though it has a wonderful ethic of loyalty, tends to narrow loyalty to the national level, thereby blocking Japan from taking its rightful place in the universal beloved community of all humankind. Many Japanese have noted this. On the other hand, I think the United States has the opposite problem. It has, if only vaguely, some kind of universal vision of some kind of universal ethic. This openness is expressed in its free-trade policies. I can go strike a bargain anywhere in the world. Yet it tends not to have loyalty to its own. In my opinion, if Japan points its loyalty in the direction of honesty, and the United States guides its honesty in the direction of loyalty, the two nations will find the proper way to relate to one another.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, the famous German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, the son of a Lutheran minister, proclaimed: "God is dead." His Anti-Christ bewailed, "Two thousand years and not a single new G. 4." Martin Heidegger, who wrote many long commentaries on Nietzsche, lamented Nietzsche's words in saying, "Only a God can redeem us" in an age of planetary technologism. Josiah Royce saw the coming new God, but this new God was in fact Paul's old God. He called Him "God the Interpreter," the Spirit who will interpret human beings to each other, as the lovers of humanity seek to incarnate the universal beloved community in "the communion of saints."

Today, I see specifically the Christian churches of the Far East playing a crucial role in manifesting God the Interpreter. I see them as having a global mission to interpret Western honesty to the Far East and Eastern loyalty to the West. In this process, our conceptions and practices of honesty and loyalty are sure to be refined in the fiery furnace of hope and faith and restored to a new luster, so that the ultimate principle of action may become part of our everyday lives. As Royce proclaimed: "So act that the Kingdom of Heaven may come!"