![]()

Explorations in Unificationism edited by Theodore T. Shimmyo and David A. Carlson

|

|

Explorations in Unificationism edited by Theodore T. Shimmyo and David A. Carlson |

Christology has two basically different approaches: "from above" and "from below."1 The approach "from above" has a storyline which moves from the divine realm above to the human realm down below: God comes down to become human. The approach "from below," by contrast, moves in the opposite direction, from the human to the divine realm: the man, Jesus of Nazareth, becomes divine. The former approach regards Christ as God rather than as a man, minimizing his human nature, while the latter approach makes Christa man rather than God, not recognizing his divine nature enough. Usually, therefore, there is a tension between both approaches, creating heated Christological controversies. The approach "from above" is represented by the traditional Christology of Niceno-Chalcedonian orthodoxy, while the approach "from below" is seen in many present-day Christologies which want to move away from Niceno-Chalcedonian orthodoxy.2

Unification Christology, the Christology of the Unification Church, has both approaches together, overcoming their tension. Its approach "from above" is reflected in its statement that Christ "should 'descend' from Heaven."3 Its approach "from below," by contrast, is seen in its fundamental assertion that Christ is a man who has perfectly attained "the purpose of creation," assuming "deity."4 In order to overcome their apparent tension, Unification Christology uses both approaches thoroughgoingly. Its thoroughgoing use of the approach "from above" is such that it makes the downward movement from the divine realm really hit the very bottom of full humanity, from which the approach "from below" normally starts. And, Unification Christology's thoroughgoing use of the approach "from below," in turn, makes the upward movement from the human realm really reach the divine realm, from which the approach "from above" usually starts. Using both approaches together this way, Unification Christology lets Christ descend from God far enough to become someone (a man) other than God and then lets him reach God again closely enough to perfectly resemble the Creator with the result that he as a man becomes someone with perfect divinity (not just with some divinity), i.e., someone who, if not God himself, is a perfect reflection of God.

As will be explained in the present essay's final section which is a more focused discussion of Unification Christology itself, the thoroughgoing use of both approaches together by Unification Christology is derived from the distinctive Unification doctrine of the "purpose of creation" which maintains that God created humans for the purpose of feeling joy from them as his perfect reflections. It seems that traditional Christianity, given its basic view of God as not in need of the existence of such perfect reflections of his own due to his status of being already completely actualized and self-contained, falls short of this Unification doctrine of the purpose of creation. Therefore, despite Unification Christology's use of the two approaches of "from above" and "from below" which emerged in the Christian tradition and despite Unification Christology's seeming resemblance to both of them resulting from its thoroughgoing use of them, still Unification Christology is quite different from them both.

First of all, Unification Christology, despite its use of the approach "from above," is quite different from this approach itself as traditionally used, in that the former makes Christ a man rather than God himself, as maintained above, whereas the latter still makes him God rather than a man. This difference needs our special attention because unfortunately there are some people, whether Unificationist or non-Unificationist, who are so anxious to stress the continuity of Unification Christology with traditional Christology that they mistakenly or even purposely obscure it.5

Second, Unification Christology, despite its use of the approach "from below," is different from this particular approach itself, in that the former makes Christ a man with perfect divinity whereas the latter usually makes him a man with some divinity only or even with no divinity.

This difference, too, needs our attention because again unfortunately there are many people, whether Unificationist or non-Unificationist, who, after learning that Unification Christology is different from the traditional approach "from above," erroneously and simplistically think that the Unification approach is merely "from below."6

From the above, it is clear that Unification Christology is not identical with the approach "from above" nor with the approach "from below." But, because of its thoroughgoing use of both approaches, Unification Christology expands and enlarges them to such a degree that they are brought together without any tension. Thus, Unification Christology has a unique ability to embrace and unify both approaches.

This is the reason why Unification Christology can reconcile the orthodox position of Nicea with Arianism, as will be seen in the final section.

As will also be discussed there, Unification Christology can even bring together the orthodox position of Chalcedon and the extreme views of Nestorianism and Eutychianism. Hence it has a very ecumenical perspective on Christ.

The real purpose of the present essay, however, is to show that because of its thoroughgoing employment of the approach "from above" as well as "from below," Unification Christology is a development and fulfillment of the traditional approach "from above" established through Niceno-Chalcedonian orthodoxy. Indeed Unification Christology is a fulfillment of Niceno-Chalcedonian orthodoxy and not a negation of it. In order to accomplish this purpose, the present essay will first explain in Sections II, III, and IV how the traditional approach "from above" was established historically through the Councils of Nicea (325), Chalcedon (451), and Constantinople (553), and then in Section V, the final section, it will discuss Unification Christology and its characteristics in the context of what is dealt with in those three preceding sections.

Using as many as three sections to explain the historical establishment of the traditional Christological approach "from above" may be too much. But I have decided that it is needed as a real context in which to persuasively discuss Unification Christology in the final section. Quite seriously, therefore, Sections II, III, and IV will respectively deal with the fourth-century Arian controversy involving the Council of Nicea, the fifth-century Christological controversy involving the Council of Chalcedon, and the sixth-century development of Neo-Chalcedonianism involving the Council of Constantinople.

To briefly explain the historical establishment of the traditional Christological approach "from above" at this point, the Council of Nicea decided, against Arianism, that the Son is of one substance (homoousios) with the Father within the Godhead, and then the Council of Chalcedon confessed against the heresies of Nestorianism and Eutychianism that the way the Son, who is divine, becomes human is such that his divine and human natures are united in one person "without confusion, without change, without division, without separation."7 From Nicea to Chalcedon, then, we see a downward movement of the Son, which starts from his divine status and then goes down to his assumption of a human nature. Hence came the traditional approach "from above." It is important to know what this traditional approach does in dealing with the two natures of divinity and humanity in the person of Christ. Because it starts from the divine status of Christ, it puts a primary emphasis upon the divinity in his person; and it basically regards the humanity merely as a secondary addendum to his person, no matter how it may try to say that Christ is truly human. Hence the sixth-century Neo-Chalcedonian doctrine of the physis anhypostatos and the physis enhypostatos, which means that the human nature of Christ has no hypostasis or person of its own, so that it finds its hypostasis only in the hypostasis of the divine Logos.8 Thus traditional Christology cannot really say that Christ has a human hypostasis or person.

Unification Christology, however, would be able to say that Christ has a fully human person because its thoroughgoing approach "from above" lets him reach the bottom level of humanity to become someone other than God. At the same time Unification Christology would acknowledge perfect divinity in the human person of Christ because its thoroughgoing approach "from below" lets him reach and unite with God perfectly.

Unification Christology is not alone in using the two approaches ("from above" and "from below") together. Martin Luther in the sixteenth century used both, proposing a unique Christology somewhat similar to Unification Christology.9 In the mid-1980s Daniel A. Helminiak, a Catholic theologian in America, published a Christological study involving a systematic use of both approaches.10 He correctly says: "The two are complementary. An adequate christology requires both. The challenge facing christologies today is to unite the two in a way that is coherent, reasonable, relevant and faithful to the Christian tradition."11 His Christology is strikingly similar to Unification Christology, although still having a considerably traditional flavor, as will be mentioned in the final section.

This section is going to deal with the fourth-century Arian controversy involving the Council of Nicea. According to Arius (d. c. 336), the Son is not of one substance with the Father: "He is neither part of God, nor of any substance."12 The Son is not related to the Father by essence but only by will. Like other creatures, the Son was created ex nihilo by the Father, so that "there was a time when He was not."13 God created the Son as the first-born of creatures and then created the whole world with the Son as his agent of creation. Hence the Son is the intermediary between God and the world, neither true God nor part of the world. Even though he is the Son of God, as a creature he is "mutable" and "subject to change."14 Arius was apparently interested to protect the oneness of God as a monotheist, when he decided that the Son is not part of God but a created being. Arius was also a follower of Origen (d. c. 254) in this matter, because the great Alexandrian had held the Son to be "a second God"15 and a creature.16

But those who were against this Arian teaching appealed to Origen's other line of thought which had affirmed the eternal generation of the Son.17 (Thus it is easy to see how Origen could be quoted on either side in the controversy.) The Council of Nicea (325), the First Ecumenical Council, led by those who were against Arianism, officially condemned this heresy. This happened under the political supervision of Emperor Constantine, but largely through the spiritual leadership of Athanasius (d. 373). Nicea formulated its creed as follows:

We believe in one God, the Father almighty, maker of all things, visible and invisible;

And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, begotten from the Father, only-begotten, that is, from the substance of the Father, God from God, light from light, true God from true God, begotten not made, of one substance with the Father, through Who m all things came into being, things in heaven and things on earth, Who because of us men and because of our salvation came down and became incarnate, becoming man, suffered and rose again on the third day, ascended to the heavens, and will come to judge the living and the dead;

And in the Holy Spirit.

But as for those who say, There was when He was not, and Before being born He was not, and that He came into existence out of nothing, or who assert that the Son of God is from a different hypostasis or substance, or is created, or is subject to alteration or change -- these the Catholic Church anathematizes.18

The four anathemas in the last paragraph of the creed were specifically directed against the Arian teaching. Noteworthy in the creed are the expressions such as: "begotten not made," and "of one substance [homoousios] with the Father." The Greek word homoousios, in spite of its not having occupied a prominent place in the Christian theological vocabulary prior to Nicea because of its associations with the Gnostics and Paul of Samosata, was nevertheless used in the creed as a test word to express the Latin consubstantialis. In the West, the consubstantiality between Christ and the Father had long been an orthodox teaching thanks to the work of Tertullian (d. c. 225) and Novatian (d. c. 257)

A question arises here, however, concerning the real meaning of the word homoousios in the creed. What did the Nicene Fathers actually mean by that word? Did they mean the Son's "numerical identity of substance" with the Father, as was traditionally believed by later Catholic theologians, or merely "generic identity of substance," as has increasingly been believed in recent years by scholars such as J.N.D. Kelly?19 Kelly has argued for generic identity of substance chiefly because of the history of the word homoousios itself prior to Nicea. Before the Council of Nicea, the word, as used by the Gnostics, Paul of Samosata, Origen, etc., had hardly meant numerical identity of substance but fundamental likeness of different substances in the generic sense. But scholars such as Edmund J. Fortman in line with the traditional interpretation have strongly argued for numerical identity for a number of reasons, one of which is that Athanasius himself endorsed that meaning.20 I would support Fortman rather than Kelly, because it seems to me that the doctrine of generic identity, supported by Kelly, would admit of two different divine ousiai unacceptable to monotheists.

Another important issue to be noted here is that while speaking of the Son's homoousios relationship with the Father within the Godhead the creed of Nicea never forgets to say also that the Son "came down and became incarnate, becoming man." This is already the traditional approach "from above." Although right after that passage we read something different, i.e., that the Son "suffered and rose again on the third

day, ascended to the heavens," which may give the impression that Nicea endorses the approach "from below" as well, nevertheless we should say that the approach "from below" hardly exists here in actuality. The reason is that according to the creed the Son is still "God from God, light from light, true God from true God," who would not have to ascend to the heavens in the sense in which someone other than God does. The approach "from below" would not really apply to "God from God" but only to someone other than God. In the creed of Nicea, therefore, only the approach "from above" can be seen. Anyway, this Nicene approach "from above" recognizes some humanity in the fully divine Son, although it does not yet touch upon how the two natures are related to each other in the Son. The relationship of the two natures was to become an important topic to be discussed only after Nicea.

After the Council of Nicea, and especially in the fifth century, the biggest theological issue was how the Son, who is fully divine because of his homoousios relationship with the Father, is also human at the same time.

Over this Christological issue of the relationship of the two natures in Christ, there were two major heretical interpretations: Nestorianism and Eutychianism. (Note, however, that these two heresies never rejected Nicene orthodoxy.) Nestorianism made a real distinction between the divine and human natures of Christ, while Eutychianism confused the two natures. Chalcedonian orthodoxy stood somewhere in between these two extreme interpretations, condemning both of them.

Nestorianism, named after Nestorius (d.c. 451), is well summarized in his own words: "With the one name Christ we designate at the same time two natures. The essential characteristics in the nature of the divinity and in the humanity are from all eternity distinguished."21 In other words, Nestorius held that Christ has only one person but two separate natures of divinity and humanity in it -- separate in such a way that the integrity of each nature is always retained. Thus he rejected the communicatio idiomatum (communication of properties) between the two natures. It was for this reason that he rejected also the description of Mary as Theotokos. Of course, he spoke of the relationship of the two natures in Christ in terms of "conjunction" (synapheia), but he preferred not to use the word "union" (enosis), except as a union of the will. Thus Nestorius seemed to endanger the essential unity of the person of Christ. His teaching was, therefore, strongly criticized by Cyril of Alexandria (d. 444), proponent of the "hypostatic union" of the two natures, and officially condemned by the Council of Ephesus (431), the Third Ecumenical Council. As a member of the school of Antioch, which appreciated the historical humanity of Christ much more than the school of Alexandria did, Nestorius separated the human nature from the divine in Christ, thus affirming two separate natures. But he would not accept the more extreme opinion of Diodorus (d. 394), founder of the school of Antioch, that there are in Christ two separate persons.

The other heresy, Eutychianism, came from the school of Alexandria whose Platonic, mystical tradition saw in Christ the full making divine of the human. Eutyches (d. 454), after whom this heresy was named, confused the two natures in Christ to say that there is only one nature after the confusion: "I confess that our Lord was of two natures before the union... but after the union one nature."22 When he thus spoke of one nature after the union, Eutyches completely absorbed Christ's humanity into his divinity in line with the Alexandrian tradition. Therefore, he naturally denied that the body of Christ was consubstantial with us. Because of his formula of one nature after the union, Eutyches became the real founder of Monophysitism. He was condemned at a local synod in Constantinople (448) and criticized by the Tome of Pope Leo I (449), which clearly set forth the Latin orthodox formula of two complete natures permanently united in one person, entertained in the West since the time of Tertullian.23 Eutyches was rehabilitated at the Robber Council (449), but was officially condemned again at the Council of Chalcedon (451).

Avoiding the two extremes of Nestorianism and Eutychianism, the Council of Chalcedon, the Fourth Ecumenical Council, attempted to offer an orthodox settlement to the Christological controversy. The Definition of Chalcedon reaffirmed the creed of Nicea as the standard of orthodoxy, setting the so-called Niceno-Constantinopolitan creed beside it. The Definition also approved Cyril's two Letters (against Nestorianism) and Leo's Tome (against Eutychianism). The essential part of the Definition is the creed of Chalcedon, which is as follows:

In agreement, therefore, with the holy fathers, we all unanimously teach that we should confess that our Lord Jesus Christ is one and the same Son, the same perfect in Godhead and the same perfect in manhood, truly God and truly man, the same of a rational soul and body, consubstantial with the Father in Godhead, and the same consubstantial with us in manhood, like us in all things except sin; begotten from the Father before the ages as regards His Godhead, and in the last days, the same, because of us and because of our salvation begotten from the Virgin Mary, the Theotokos, as regards His manhood; one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, only-begotten, made known in two natures without confusion, without change, without division, without separation, the difference of the natures being by no means removed because of the union, but the property of each nature being preserved and coalescing in one prosopon and one hypostasis -- not parted or divided into two prosopa, but one and the same Son, only-begotten, divine Word, the Lord Jesus Christ, as the prophets of old and Jesus Christ Himself have taught us about Him and the creed of our fathers has handed down.24

According to this creed, Christ has only one person (prosopon or hypostasis) in which his two perfect natures of divinity and humanity, being respectively "consubstantial with the Father" and "consubstantial with us," are united "without confusion, without change, without division, without separation" (asynchytos, atreptos, adiairetos, achoristos). Of the four celebrated negative adverbs, the first two are directed against the heresy of Eutychianism and the last two against the heresy of Nestorianism. Thus the creed affirms both the unity and the distinction of the two natures in Christ at once with a good balance. The unity of the two natures is seen not only in the anti-Nestorian expression, "without division, without separation," but also in the repetitive use of the words "the same" for one and the same person of Christ and in the adoption of the title Theotokos for Mary. (Note, however, that the creed does not use the Cyrillic expression "hypostatic union.") The distinction of the two natures is seen not only in the anti-Eutychean expression, "without confusion, without change," but also in the phrase, "in [en] two natures," of the final version of the creed, which replaced the first draft's phrase, "from [ek] two natures."25 Understandably, the creed of Chalcedon is a mosaic of excerpts from Cyril's two Letters, Leo's Tome, and so on. Chalcedonian orthodoxy took a position midway between Nestorianism and Eutychianism, and more generally, between the schools of Antioch and Alexandria.

Traditional Christology was shaped by the two most important Ecumenical Councils: the Council of Nicea, which "has always lived in Christian tradition as the most important in the history of the church,"26

and the Council of Chalcedon, whose creed is "theologically second only to [the creed of Nicea] in importance."27 The Council of Nicea acknowledged the full divinity of the Son, the second person of the Trinity, by affirming his homoousios relationship with the Father. The Council of Chalcedon, too, acknowledged the full divinity of Christ, reaffirming the creed of Nicea as the standard of orthodoxy, but it did something more. It acknowledged the full humanity of Christ as well and said that the two full natures are united in one person "without confusion, with out change, without division, without separation." Thus traditional Christology starts "from above," i.e., starts by talking about the divinity of Christ and then goes on to deal with his humanity.

What is characteristic of this traditional approach "from above" is its main emphasis upon the divinity in the person of Christ, because its starting point is the Nicene doctrine of homoousios. So, even though the Council of Chalcedon itself acknowledges the full humanity of Christ and affirms a good balance of unity and distinction of the two natures in the person of Christ, nevertheless Christology in the continuous tradition of Niceno-Chalcedonian orthodoxy cannot help viewing the human nature of Christ merely as a secondary addendum to his person which is considered to be primarily divine. In other words, traditional Christology "from above" cannot help believing that the human nature of Christ has no hypostasis or person of its own.

If the human nature of Christ has no hypostasis of its own, however, the relationship between his human nature and his hypostasis is far from clear. The Definition of Chalcedon was not very clear yet about this relationship. Hence Joseph Ayer says: "The definition [of Chalcedon] was... not preceded by any clear understanding of what was to be understood by nature in relationship to hypostasis."28 Therefore, the sixth-century Neo-Chalcedonian development to clarify this point had to occur naturally.

The Neo-Chalcedonians were those who interpreted the creed of Chalcedon in a Cyrillic sense in order to incorporate the moderate Monophysites into Chalcedonian orthodoxy. In the fifth century, Cyril of Alexandria, putting much emphasis upon the divinity of Christ in his doctrine of hypostatic union, had said that the humanity of Christ is little more than a non-hypostatic or impersonal nature. Along this line there came in the sixth century the Neo-Chalcedonian teaching that the humanity of Christ is a physis anhypostatos, having no hypostasis of its own. In this connection, one important further suggestion was made by Leontius of Byzantium (d. 543) on the basis of the Aristotelian categories. According to him, a nature or species cannot be conceived of except as exemplified in a hypostasis which is a particular subsisting entity, so that no nature is really non-hypostatic. Therefore, the humanity of Christ as a physis anhypostatos should be understood to be a physisenhypostatos, i.e., a nature which finds its hypostasis only in the particular hypostasis of the divine Logos. This interpretation of Leontius greatly assisted Emperor Justinian's Neo-Chalcedonian cause. Justinian convened the Council of Constantinople (553), the Fifth Ecumenical Council, which condemned the so-called "Three Chapters" as sympathetic to Nestorius.29

The Neo-Chalcedonian doctrine of the physis anhypostatos and the physis enhypostatos was a natural outcome of Niceno-Chalcedonian Christology "from above," even though it had not been explicitly indicated in the Definition of Chalcedon. Thus many of the Christologists "from above" in Christian orthodoxy referred to this Neo-Chalcedonian doctrine as authoritative. For example, Karl Barth in this century upheld this doctrine and in this connection stated: "It is only as the Son of God that Jesus Christ also exists as man."30

Because of this doctrine, Christian orthodoxy has not even hesitated to say, if in a rather non-technical way, that Christ is God.

Unification Christology lets Christ become someone other than God, by carrying out the approach "from above" thoroughgoingly. It does not let Christ stop somewhere on his way down to the bottom of full humanity, unlike traditional Christology which, because of its non-thoroughgoing approach "from above," lets him stop only somewhere in the middle in which he assumes just some humanity called the physis anhypostatos.

According to Unification Christology, Christ, after originating from God, becomes a perfect outer manifestation of God, so that he is someone other than God, yet perfectly reflecting God. Here we have two important things: 1) the origination of Christ from God, and 2) the perfect outer manifestation of God in the distinct person of Christ. Regarding the former, Unificationism says that Christ "should 'descend' from Heaven,"31 and regarding the latter, it asserts that as a perfect outer manifestation of God "he can by no means be God Himself."32 The latter is the inevitable fulfillment of the former, if the approach "from above" is carried out thoroughgoingly. Unification Christology, because of its thoroughgoing use of this approach, talks about both things, while traditional Christology, because of its non-thoroughgoing use of it, basically speaks of the former only. Thus Unification Christology is an inevitable development and fulfillment of traditional Christology.

Unification Christology's thoroughgoing use of the approach "from above" is necessitated by the Unification doctrine of the purpose of creation."33 According to Unificationism, God created humans and the rest of the universe for the purpose of feeling joy from them and sharing joy with them. What is important is: "Joy is not created by the individual alone";34 joy is felt only when you have an object, whether visible or invisible, in which your own character and form are developed and reflected. This applies to God also; joy cannot be produced by him alone. He needs his objects for joy. So, he wants Christ to be his object, in whom his character and form are developed and reflected, so that he may be able to feel joy from him. To be God's object in this sense means to be someone other than God. If Christ were not someone other than God but merely "God from God, light from light, true God from true God" as the creed of Nicea says, then God would not feel joy fully from Christ The purpose of creation, then, would not be fully accomplished.

The purpose of creation necessitates also Unification Christology's thoroughgoing use of the approach "from below." In order for God to feel perfect joy which is the purpose of creation, Christ, after coming down to become someone other than God, should go up to reach and unite with God perfectly, thus reflecting God's character and form perfectly. In other words, in order to attain the purpose of creation perfectly, Christ as a fully human person should reach God to become his perfect reflection, assuming perfect divinity. This is none other than Christ's upward movement from the level of full humanity to that of perfect divinity. Hence, Unification Christology's thoroughgoing approach "from below."

According to Unificationism, the "value" of a man who has perfectly attained the purpose of creation is such that he lives "in perfect union with God's heart and feeling," becomes "the temple of God's constant abode," and assumes "deity."35 Christ, if approached "from below" thoroughgoingly in Unification Christology, is a man of this value who has attained the purpose of creation:

Jesus is truly a man of this value. However great his value may be, he cannot assume a value greater than that of a man who has attained the purpose of creation. Therefore, we cannot deny that Jesus was a man who had attained the purpose of creation.36

...Jesus, as a man having fulfilled the purpose of creation, is one body with God. So, in light of his deity, he may well be called God. Nevertheless, he can by no means be God Himself.37

From the above, we can realize that the Unification doctrine of the purpose of creation enables Unification Christology to employ both approaches ("from above" and "from below") consistently. To say that the purpose of creation, which is joy, should be perfectly attained requires the thoroughgoing use of the approach "from above," which in turn requires the thoroughgoing use of the approach "from below." Hence centering upon the purpose of creation, the first approach is completed by the second. Daniel A. Helminiak, arguing for the complementarity of the approaches "from above" and "from below" from a Catholic perspective, says virtually the same thing: "The first movement of christology leads to a second. Without it the first was not to be completed. What was possible in the first movement still needed to be made actual in the second."38

Helminiak's position, harmonizing both approaches, is strikingly similar to Unification Christology. But there is at least one difference, which should be mentioned here to further clarify Unification Christology. Helminiak believes that Christ still maintains his divine identity as God even after becoming fully human by leaving his divinity behind in his downward movement:

He surrendered his former principle of activity, divinity, and limited himself to a new principle of activity, humanity. This does not mean that he stopped being God. His divinity is indistinguishable and inseparable from himself as Eternally-Begotten-of the-Father. Nonetheless, he prescinded from acting as divine when he became human.39

Thus, although Helminiak quite boldly goes beyond traditional Christology in that he lets Christ give up his divinity in the process of the Incarnation, nevertheless this Catholic thinker still has some important allegiance to traditional Christology because he never lets Christ give up his divine identity as God. By contrast, Unification Christology is very different from traditional Christology, for it never regards Christ's identity as God, even though it accepts his origination from God. This difference between Helminiak's position and Unification Christology has much to do with the above-mentioned notion of the purpose of creation. Apparently, Helminiak does not have as much awareness of this important notion as Unificationism does. Thus it can be said that his approach "from above" is not thoroughgoing enough.

From the above discussion, it is clear that Unification Christology, due to its thoroughgoing use of the approach "from above," does not accept the Nicene formula of homoousios which undoubtedly regards Christ's identity as God. Thus Unification Christology is not Nicene. Is it, then, Arian? The answer is that it is not so, either. There are at least two reasons why Unification Christology is not Arian. In the first place, Unification Christology, because of its thoroughgoing use of the approach "from below," recognizes full divinity in the man Christ, whereas Arianism completely denies him divinity. The other reason is that Unificationism does not literally agree with the doctrine of creation ex nihilo which Arianism accepts. These two reasons are interrelated to each other. For Unificationism maintains, based upon its unique doctrine of creation,40 that it is possible for a creature to assume divinity, whereas Arianism believes on the ground of the doctrine of creation ex nihilo sharply distinguishing between the Creator and a creature that the creature cannot assume any divinity.

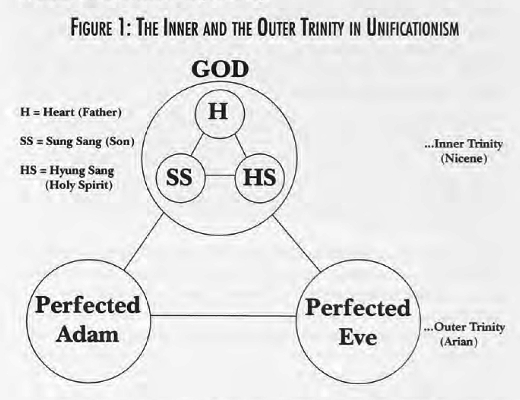

Figure 1: The Inner and the Outer Trinity in Unificationism

Therefore, Unification Christology is neither Nicene nor Arian. But if we further examine Unification Christology from the perspective of the Unification doctrine of the Trinity, we can realize that in a way Unification Christology is both Nicene and Arian at once. For, according to Unificationism, there are two kinds of Trinity at the same time: the inner and the outer Trinity (the latter being the outer manifestation of the former as a result of God's act of creation),41 and in a way the former is Nicene and the latter Arian. For the sake of visual clarity, see Figure 1. The inner Trinity is the divine threeness constituted by God's three major attributes: "Heart," "Sung Sang," and "Hyung Sang,"42 which are respectively equivalent to the three divine persons within the Godhead as traditionally understood: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. By contrast, the outer Trinity is constituted by three elements: God, perfected Adam (Logos incarnate), and perfected Eve (Holy Spirit incarnate).43 While the three attributes of God in the inner Trinity share one and the same substance of God the three elements in the outer Trinity have their own different, if similar, substances for the reason that perfected Adam and Eve are not God, but created individuals. While the three in the inner Trinity are homoousios with one another, the three in the outer Trinity are homoiousios to one another. In this sense, the inner and the outer Trinity in Unificationism are Nicene and Arian, respectively.44 (This means that Nicene orthodoxy failed to see the outer Trinity, while Arianism failed to recognize the inner Trinity.) Of course, the outer Trinity is not exactly Arian for the reason that perfected Adam and Eve in that Trinity can assume perfect divinity according to Unificationism, whereas they would be denied divinity in Arianism and Semi-Arianism. But still the outer Trinity is Arian for the above reason.

From the preceding discussion we can say that Unification Christology has a broad perspective to be able to contain both Nicene orthodoxy and Arianism, while at the same time it is not exclusively Nicene nor Arian. In this sense, Unificationism is like Origenism which was quoted by both Athanasians and Arians in the Arian controversy.

Let us now proceed to examine whether Unification Christology is Chalcedonian, Nestorian, or Eutychean. It is quite easy to see that it is neither Chalcedonian nor Nestorian nor Eutychian, for the three schools (i.e., Chalcedonian orthodoxy, Nestorianism, and Eutychianism), in spite of their divergent interpretations of the two natures of Christ, all presuppose the Nicene formula of homoousios which regards Christ's identity as God. Unification Christology, due to its thoroughgoing use of the approach "from above," does not accept this Nicene formula.

But if we have a little adventure to consider the three schools in themselves, disconnecting them from the Nicene formula, then perhaps we can say that Unification Christology is in a way Chalcedonian, Nestorian, and Eutychian. Let me explain this.

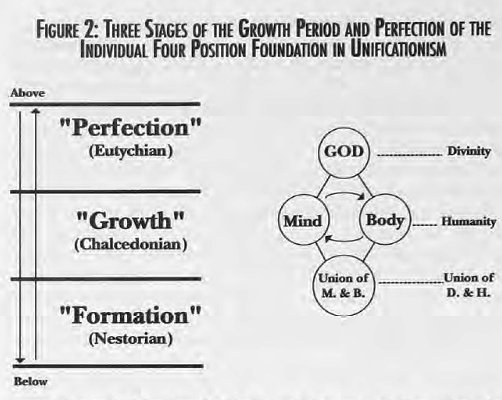

Figure 2: Three Stages of the Growth Period and Perfection of the Individual Four Position Foundation in Unificationism

According to Unification Christology, which uses the two approaches of "from above" and "from below" thoroughgoingly, once Christ is made someone other than God (the thoroughgoing approach "from above"), he has to assume perfect divinity by perfecting the purpose of creation within himself (the thoroughgoing approach "from below"). For that purpose he has to go through the three stages of "formation," "growth," and "perfection" in the growth period,45 proceeding from below to above to perfect the union of divinity and humanity within himself based upon the "individual four position foundation" which involves four elements: God, mind, body, and their union.46 It is schematized in Figure 2 for the sake of visual clarity. Here the point is that the three stages of "formation," "growth," and "perfection" are respectively Nestorian, Chalcedonian, and Eutychian in the sense to be shown below.

In the four position foundation, God is the source of Christ's divinity; Christ's mind and body represent his humanity; and the union of his mind and body centered upon God represents the union of his divinity and humanity in his person.47 As Christ proceeds from below to above in the process of his growth, the degree of the union of his mind and body increases, so that the degree of the union of the two natures increases, too. In the "formation" stage in which his mind is still a "form spirit," the union is still rudimentary, so that the two natures of divinity and humanity are basically still distinct from each other. In the "growth" state in which his mind is a "life spirit," the degree of the union is intermediary, so that it has both unity and distinction of the two natures. In the final "perfection" stage in which his mind becomes a "divine spirit," the union of his mind and body is perfected centered upon God, so that the union of the two natures is perfected.48 Thus the three stages in Unificationism are Nestorian, Chalcedonian and Eutychian, respectively, if the three schools are considered in themselves in separation from the Nicene formula.

As has been seen so far, Unification Christology is neither Nicene nor Arian, neither Chalcedonian nor Nestorian nor Eutychian, while at the same time being able to embrace all these different schools of theology. This means that Unification Christology is neither orthodox nor heretical, while at the same time having the capacity to appreciate both orthodoxy and heresies. Unificationism, then, has a broader, bigger and more ecumenical picture of Christ than Christian orthodoxy. Helminiak's Christology, which uses the two approaches of "from above" and "from below" together, makes a similar claim: "This 'model,' a paradigm, would be capable of absorbing and integrating all the other models of Jesus."49

But the question might arise: Is Unification Christology with its broader perspective really Christian? I answer this question in the affirmative for at least two reasons.

In the first place, Unification Christology with its broader perspective can embrace all the Christian schools in question (including the Christian heresies such as Arianism), even though it does not exclusively accept any of them. Therefore, it must be Christian.

The above reason has a certain weakness, however, for it could be argued against it that Unification Christology is unChristian because it is neither Nicene nor Arian, neither Chalcedonian nor Nestorian nor Eutychian. So we need a second, much stronger, reason. The second reason, I suggest, is that Unification Christology is a fulfillment of Niceno-Chalcedonian Christian orthodoxy, so that it must be Christian. Niceno-Chalcedonian orthodoxy did a good job in its approach "from above," describing Christ as having originated from none other than God. But it basically stopped at that point without going further. Hence the orthodox formula of the physis anhypostatos and the physis enhypostatos. Unification Christology goes further than this point, by saying that Christ, after originating from God, becomes a perfect outer manifestation of God, so that he is someone other than God, yet perfectly reflecting God. This is Unification Christology's thoroughgoing approach "from above," which in turn necessarily results in its thoroughgoing approach "from below." Thus Unification Christology is a development and fulfillment of traditional Christian Christology, without abandoning it. In this sense, Unification Christology is definitely Christian. Traditional Christology has been accepted as orthodox by all major Christian Churches (Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Lutheran, Reformed, Anglican, Methodist, and so forth). But today there is a strong trend among Christian theologians to move away from it. In reaction to the traditional approach, they approach "from below," from the historical Jesus, saying that he is not God but a man, a real man. They have a weakness, however, in that they strongly tend to be Arian, minimizing the divine nature of Christ. Unification Christology can remedy this weakness in such a way as to reconcile this present-day trend with Christian orthodoxy, because as a fulfillment of Christian orthodoxy the Unification approach regards Christ's human reality as the inevitable fulfillment of his divine origin. Hence Unification Christology is a viable alternative Christology.

1. For these two different approaches, see, for example, Gerald O'Collins, What Are They Saying About Jesus? (NY: Paulist Press, 1977), 1-34.

2. For present-day Christologies which want to move away from Niceno-Chalcedonian orthodoxy, see, for example, Klaas Runia, The Present-Day Christological Debate (Leicester, England: Inter-Varsity Press), 1984.

3. Divine Principle (NY: HSA-UWC, 1973), 214. This book, regarded as the normative text for Unification doctrine, has a chapter on "Christology," 205-18.

4. Ibid., 209.

5. For example, Jonathan Wells, a Unificationist, obscures the difference this way in his article, "Unification Christology," in Unity in Diversity: Essays in Religion by Members of the Faculty of the Unification Theological Seminaty, ed., Henry O. Thompson (NY: Rose of Sharon Press, 1984), 135-47, where he states "that Unification Christology falls within the bounds of Christian orthodoxy in its description of Jesus Christ, and that Christian orthodoxy does not exclude or proscribe the less traditional aspects of Unification Christology" (136). A mistaken move of the same kind has been made by Sebastian A. Matczak, a non-Unificationist, in his Unificationism: A New Philosophy and Worldview (NY: Learned Publications, 1982), where he asserts that "the explanation which traditional Christianity offers may be reconciled with the general position of Unificationism concerning the person of Jesus" (335).

6. For example, Durwood Foster, a non-Unificationist, has this kind of misunderstanding of Unification Christology in his article, "Unification and Traditional Christology," in Ten Theologians Respond to the Unification Church, ed. Herbert Richardson (NY: Rose of Sharon Press, 1981), 179-99, where he decides that Unification Christology is "typically a 'low' Christology of the Antiochen type" (183). Note, however, that his erroneous understanding in this regard is somewhat compensated for by his later statement that Unification Christology is "just now undergoing vigorous evolution" (188) with "a potent disposition toward alliance and resynthesis with the Christian heritage (189). Even Unificationists such as Young Oon Kim tend to have this erroneous understanding. Kim, in her Unification Theology, NY: HSA-UWC, 1987, does so by arguing that "Unificationism agrees with the recent trends [of the approach 'from below'] in Christology that Jesus was human, as well as somehow divine" (162).

7. So says the creed of Chalcedon. See J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines (NY: Harper and Row, Publishers, 1978), 340.

8. Hubert Cunliffe-Jones, ed., A History of Christian Doctrine (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1981), 143-44.

9. Luther accepted the orthodoxy of Nicea and Chalcedon (the approach "from above"), while at the same time suggesting as a Biblical exegete to start from the man Jesus of Biblical witness (the approach "from below"). The outcome was his assertion, somewhat similar to Unificationism, that "Christ is not the person of the Logos existing as man, but rather the concrete existential/historical being composed from and out of a divine and a human nature," in the words of Thomas G. Weinandy in his Does God Change?: The Word's Becoming in the Incarnation (Still River, MA: St. Bede's Publications, 1985), 104.

10. The Same Jesus: A Contemporary Christology (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1986).

11. Ibid., 46.

12. Joseph Cullen Ayer, Jr., A Source Book for Ancient Church History (NY': AMS Press, 1970), 302.

13. Ibid., 303.

14. Ibid., 303-4.

15. Origen, Contra Celsum, trans. Henry Chadwick (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 296.

16. Ibid., 294.

17. In his First Principles, trans. G.W. Butterworth (London: S.P.C.K., 1936), 18, Origen says: "This is an eternal and everlasting begetting, as brightness is begotten from light."

18. Kelly, 232.

19. Ibid., 233-37.

20. Fortman, The Triune God: A Historical Study of the Doctrine of the Trinity (Grand Rapids, Ml: Baker Book House, 1972), 67-68.

21. Ayer, 502.

22. Ibid., 514.

23. It is important to note that Leo's Tome, while being opposed to Eutycheanism, never forgets to affirm the communicatio idiomatum.

24. Kelly, 339-40.

25. Later the expression, "from two natures," becomes the slogan of Monophysitism.

26. Williston Walker, A History of the Christian Church (NY: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1970), 108.

27. Ayer, 516.

28. Ibid., italics mine.

29. The Three Chapters are: 1) the person and work of Theodore of Mopsuestia, 2) the writings of Theodoret of Cyrus against Cyril of Alexandria and 3) the letter of Ibas of Edessa to Maris.

30. Church Dogmatics, IV/2 (London: T.andT. Clark, 1961), 91.

31. Divine Principle, 214.

32. Ibid., 210-11.

33. Ibid., 41-46.

34. Ibid., 42.

35. Ibid., 206.

36. Ibid., 209.

37. Ibid., 210-11.

38. The Same Jesus, 164.

39. Ibid., 161-62.

40. Unificationism holds that God created the world not ex nihilo but out of his own attributes. For a detailed account of it, see Sang Hun Lee, Explaining Unification Thought (NY: Unification Thought Institute, 1981), 34-36. Note that Unificationism is not pantheistic.

41. The expression, "the inner and the outer Trinity," was coined by me. The two kinds of Trinity in Unificationism are somewhat similar to the essential Trinity and the economic Trinity, respectively, in the Christian tradition.

42. Lee, Explaining Unification Thought, 29. According to Lee, "Heart" is God's "emotional impulse to seek joy through love' (21); "Sung Sang" is "the mind of God, or the attribute of God that constitutes the fundamental cause of the invisible, functional aspects of all existing beings" (6-7); and "Hyung Sang" is "the attribute of God that constitutes the fundamental cause of the material aspect of all existing beings" (10). Sung Sang and Hyung Sang are Korean words, roughly translated as "internal character" and "external form," respectively (xxii). God's Sung Sang and Hyung Sang can also beregarded as "Logos" (35) and "pre-energy" (10), respectively.

43. Divine Principle, 217.

44. The consubstantiality of the Holy Spirit was affirmed at the Council of Constantinople (381) in continuity with the Nicene tradition and against the Semi-Arians (Macedonians) who rejected it.

45. Ibid., 53.

46. Ibid., 43.

47. Thus Unification Christology also differs from Apollinarianism, which replaces Christ's human mind by the divine Logos.

48. For the terms, "form spirit," "life spirit" and "divine spirit," see Divine Principle, 62.

49. The Same Jesus, 158.