![]()

Proceedings of the Virgin Islands' Seminar on Unification Theology -- Darrol Bryant, General Editor - April 1, 1980

|

|

Proceedings of the Virgin Islands' Seminar on Unification Theology -- Darrol Bryant, General Editor - April 1, 1980 |

The Divine Principle has three fundamental parts. The first is what we will cover during this morning's session, and that is called the principle of creation.1 The principle of creation deals with the nature of God and the principles by which he has created and sustained the world. The second major part is called the fall of man. It deals with man's deviation from God's original principle. The third part comprises a number of chapters, which may be referred to collectively as the history of restoration. It explains how God intends to restore man back to the original ideal.

First, let me put this in perspective. A result of the fall of man is that man's spirit has decayed. Subsequently, God's communication with man has been proportionate to the redevelopment of our spirit -- as development in our spirit takes place, God is able to communicate more of his nature. The Old Testament is a foundational communication with man through which we learn certain elementary principles of God. The New Testament is a deeper expression of God's nature and will, but there is clearly more to come. In John 16:12,25 Jesus says, "I have yet many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now... the hour is coming when I shall no longer speak to you in figures but tell you plainly of the Father."

In this context we see the appearance of Rev. Moon's teachings. Rev. Moon has explained that his teachings are not something that he has based simply on what he has studied. He describes them as coming from revelations that were given to him by God -- revelations which led him to a deeper understanding of God's nature and will and his providence of salvation.

On that foundation, I will present the principle of creation. We can begin to understand God's nature and his principles by looking at the world. Paul says in Romans 1:20, "Ever since the creation of the world his invisible nature, namely, his eternal power and deity, has been clearly perceived in the things that have been made." However, in order fully to understand God and his principles, we need to do more than just look at the creation. We also need to look at the Bible because God has tried to teach us through the prophets and through Jesus Christ. By viewing the creation through biblical revelation, and ultimately by relating to Christ himself, by experiencing his presence and life, we can understand the nature of God.

Let's begin by looking at the creation. Since the world was made by God, we assume we can understand something of his nature by looking at it just as we can understand something of an artist or an author by looking at what he has created. When we look at the creation with this in mind, we find polarity. We find two primary kinds of polarity. The first that we'll talk about is the polarity of positivity and negativity, or masculinity and femininity. (When we talk about positivity and negativity in this case, we're not referring to good and evil, but to polarity of the sort that we find in protons and electrons.) Such polarity is universal: man and woman in the case of mankind, male and female in most animals, stamen and pistil in many plants, cation and anion in the molecules, atoms of positive valence and negative valence, particles with plus and minus charges.

Now created beings presumably could not have such polarity if it were not also in the nature of the Creator. For biblical support we turn to Genesis 1:27, which says that "God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them." Man and woman together are mankind, the image of God; and God has this polar nature within himself, the polar nature of positivity and negativity or masculinity and femininity.

There is another polarity within God also -- one which is actually more fundamental -- and that is the polarity of internal character and external form, or in the original Korean, sung sang and hyung sang. For instance, in human beings we have mind and body. In animals we have something which can be called the animal mind or instinct, as well as the animal body. Even in plants, we find what some people call a plant mind. There is an inherent directive nature within living organisms, and ultimately also within molecules, atoms and particles. The dual aspects of internal character and external form are universal. They, too, presumably reflect the nature of God. So then, God is a being of internal character and external form, or of sung sang and hyung sang, as well as a being of positivity and negativity, or masculinity and femininity.

What is the relationship between positivity and negativity and sung sang and hyung sang? Positivity and negativity, or masculinity and femininity, are attributes of internal character and external form. Human beings are fundamentally beings of mind and body, and secondarily beings of masculinity and femininity.

The relationship between sung sang and hyung sang is that of subject and object. The subject is the position which initiates or stimulates, whereas the object is in the position which responds to the stimulus. The relation between sung sang and hyung sang is also one of vertical to horizontal. In other words, internal character relates to the past, present and future, transcending time and space; whereas external form is limited in time and space. So it is through the sung sang that we relate vertically to God, who transcends time and space. The hyung sang essentially reflects sung sang. They are not fundamentally separate or independent, and one cannot exist without the other.

Each individual being contains sung sang and hyung sang, and positivity and negativity, and therefore reflects the dual characteristics of God. So each being is an "individual truth body," an incarnation of the fundamental nature of God. However, we can make a distinction between people and the other beings of creation. People are created to be the image of God; that is, created to reflect the full nature of God, whereas the other beings of the creation are created to be symbols of God; that is partial expressions of the truth or the beauty that is within the Creator.

Since God is the origin of all dual characteristics, his internal character and external form are called "original sung sang" and "original hyung sang." God's original hyung sang is like energy: not physical energy, but "universal prime energy," about which I will have more to say in a minute. God's original sung sang includes such qualities as beauty, goodness, principle and law; but at the most fundamental level, God's internal character is heart and love. Of course, these qualities are not separate and distinct, but rather are entirely harmonized within God. Thus, we can refer to God as the harmonized subject of dual characteristics.

At this point I would like briefly to distinguish between this view and some aspects of oriental philosophy. For example, Taoist philosophy includes the polarity of positivity and negativity, or masculinity and femininity. However, in addition to this polarity, the Divine Principle speaks of internal character and external form, which enables it to describe the Creator as a being of will, heart and purpose. And we can have a relationship of heart and love with our Creator. That is a parent-child relationship. This understanding of the personal is rarely found in oriental philosophy. Furthermore, oriental philosophy does not really clarify the nature and origin of evil, and tends to identify it as a permanent polarity in God and the creation. But the Divine Principle is not dualistic in this sense. God is entirely good, and so is the original creation.

Now, I want to talk about the basis of existence. God is eternal, absolute and unchanging, a self-existing being. According to the Divine Principle, there is a fundamental force within God: the "universal prime force (or energy)," the original force from which all other forces are derived. Universal prime force is generated by give-and-take action within God. Furthermore, universal prime force allows the created beings to enter into give-and-take relationships, or perhaps more accurately, giving and receiving relationships, without which beings cannot maintain their own existence. In fact, give-and-take relationships are the basis for all existence, development, and multiplication. For example, atoms exist by virtue of relationships between protons, electrons and neutrons. Living organisms exist, develop and multiply by virtue of give-and-take relationships such as respiration, nutrient uptake and elimination, and circulation. Families and societies exist and develop by virtue of relationships between individuals. If these giving and receiving relationships break down, then so does the basis for existence, development and multiplication.

Now, give and take, or giving and receiving action, is initiated on the foundation of two things. The first is common purpose. There must be a common purpose between subject and object in order for a relationship to result which we would call a giving and receiving relationship. Secondly, the action of giving and receiving begins with giving. It is not the other way around. Taking, or receiving, cannot initiate the relationship. Furthermore, ideal existence, ideal of development and proper multiplication come about through God-centered give-and-take action.

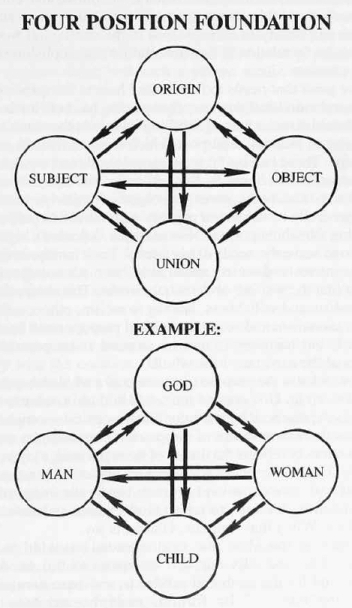

When two created beings unite to form a subject-object relationship, a new being results. The origin, division and union, taken together, then form a "four position foundation."

Within this four-position foundation each being can act as object (or subject) to the other three, thus fulfilling a "triple objective purpose." God creates each being to enter into this type of relationship in such a way that God is the primary object of relationship. The fulfillment of the triple objective purpose, centered on God, is the foundation for the expression of God's love, and beauty, goodness and energy in the creation. Without this, there is no way for God's power and love and goodness and beauty to be expressed in the substantial world. So the four-position foundation is fundamental for accomplishing God's purpose of creation.

One point that needs to be clarified here is the question of whole purpose and individual purpose. Every being has both a whole purpose which should direct it toward fulfilling its role in the community or the world, and an individual purpose which leads to its own survival and fulfillment. These two ought to be harmonized, and a proper harmony would resemble the harmony between mind and body. Mind is generally subject, and body, generally object. Similarly, whole purpose should generally be subject or primary and individual purpose, object, supporting the whole purpose. For example, a person's higher purpose would be to serve the needs of his family. Each family, in turn, should place the interests of society ahead of its own. And each nation should consider first the welfare of the whole world. The alternative to this is individualism and selfishness, leading to racism, ethnocentrism, exaggerated rationalism and so on. Individual purpose must not be ignored or denied, but harmony cannot be attained if we pursue individual purposes at the expense of the whole.

Now, what is the purpose of creation as a whole? According to the Divine Principle, God created the world and us in order to experience joy. Joy is experienced by a creator when a creation completely fulfills or reflects the will or desire of the creator. For example, a work of art which accurately reflects the dream of the artist brings joy to its creator. Similarly, God experiences joy when an object fully reflects his own ideal and will. Since mankind is created to be the image of God, it is mankind that is able fully to reflect God's nature and to fulfill his will and desires. When that happens, God feels joy.

What was the ideal that God intended mankind to fulfill? In Genesis 1:28, God tells our first ancestors to "...be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion... over every living thing..." Be fruitful, multiply, and have dominion. It is God's will or desire that mankind should do these things; and when mankind carries them out fully and completely, God will experience joy. The Divine Principle refers to these ideals as the three great blessings.

The first blessing is to be fruitful, which means to become perfect. Jesus says, in Matthew 5:48, that we must become perfect as our heavenly Father is perfect. In a perfect individual, mind and body are united centering on God. A perfect man or woman is the one whose thoughts and desires are one with God's, and whose actions and way of life are one with God's way of life. Such a person could be said to possess deity, and such a person would never sin. Jesus was such a person.

The second blessing is to multiply, and it is fulfilled when a perfect man and perfect woman unite in marriage and have children without original sin. If our first ancestors had fulfilled the first blessing, they would have become the perfect image of God, and they would have begun their marriage under the blessing of God as the true parents of mankind, establishing the kingdom of heaven on earth from the very beginning. Their God-centered family relationship would have been the foundation for the full expression of God's love. God's love would then be expressed in three fundamental forms: parental love or the love of parents for their children; conjugal love or the mutual love of husband and wife; and filial piety, or the love of children for their parents.

The third blessing is to have dominion over the creation, and it is fulfilled when a perfect man or woman enters into a God-centered relationship with the creation. The result would be an ideal environment. The key would be a God-centered relationship in all these things. However, because of the fall (which is the topic of our next lecture), our first ancestors failed to fulfill the three blessings. As a result, we now have something less than perfect men and women, something less than perfect families and perfect children and something less than an ideal environment.

Participant: Is the first blessing realizable without the second and third? Can a man or woman become perfect without entering into the other two?

Joe Tully: Yes, in fact, the first must be fulfilled before the second and third can be fulfilled properly. Nonetheless, it is true that a perfect individual has not experienced the fullest love of God until he or she has fulfilled all of the three blessings.

I would like to speak about the three stages of growth. According to Genesis, God created the world in six days. We can think of these "days" as six periods of time. Creation takes time. Furthermore, we can observe in the world around us that every living thing needs time to grow to its "perfect" or mature stage. The number three is often symbolic of completion in the Bible; and Divine Principle divides the growth period into three stages: the formation stage, the growth stage, and the perfection or completion stage. For example, the formation stage of a plant is the seed, the growth stage is the young plant, and the completion stage is the mature flowering plant. Similar stages can be seen in the life of a human being.

However, there is an important difference between the process of growth in human beings and the process of growth in the rest of the creation. Normally, created beings grow to perfection automatically in accordance with natural law. Human beings grow to maturity naturally as far as their physical bodies are concerned, but their spiritual development is not automatic. In order for us to grow to perfection spiritually, we must fulfill our portion of responsibility. I will explain more about what I mean by "spiritual" in a minute. But first let me say something about our portion of responsibility.

When a person reaches perfection, he or she is under the "direct dominion" of God. This means that such a person is dominated by the full love of God, as God's son or daughter. He or she shares God's heart and desires and would never sin. Such a person would also share in God's creativity, exercising dominion over the creation. But in order to be a son or daughter of God, a person must be free, as God is, and must exercise that freedom responsibly in order to grow to perfection. Since God cannot relate directly to something which is imperfect, a person in the growth stage is under the "indirect dominion" of God and is guided primarily by law or principle. The commandment which God gave our first ancestors (Genesis 2:17) was intended to guide them through the growth stage to individual perfection. If they had fulfilled their responsibilities by obeying the commandment, they would have become co-creators with God by contributing to their own spiritual development. They would then have been qualified to be a true son and a true daughter of God.

According to the Divine Principle, the creation consists of two realms, the physical and the spiritual -- the spiritual realm is called the "invisible substantial world" to indicate that although it is presently invisible to us, it is nonetheless substantial. Human beings are distinguished from the rest of the creation in that they are both physical and spiritual. In other words, during life on earth a person consists of a physical self and a spiritual self. Just as there is a physical sung sang and hyung sang, so there is a spiritual sung sang and hyung sang. The physical mind is concerned with the material dimension: food, temperature, work, and other factors that relate to our physical body. The spirit mind is concerned with truth, beauty, goodness, justice, and other values that relate to spiritual life. Just as there are five physical senses, so there are also five spiritual senses. Normally, our spiritual senses would enable us to perceive the invisible substantial world; but the spiritual death caused by the fall deprived us of our spiritual senses under all but the most extraordinary circumstances such as when the disciples saw the spirits of Moses and Elijah at the Mount of Transfiguration (Matthew 17:3).

Now, the physical self needs certain nutrients to survive and grow, such as food, water, sunlight and air. The spiritual self also needs certain things in order to function and develop. It must receive what we call "life elements" from God, namely God's love and truth. Without these the spirit is not able to develop properly. However, something else is also needed for proper spiritual development: that is vitality elements from the physical self. These vitality elements can either be good or bad depending on the activities of the physical self. If a person lives a morally upright life, the vitality elements will be good and will nourish the spirit. But if a person lives immorally, the vitality elements will be bad and will poison the spirit. So spiritual growth depends on two factors: life elements from God and vitality from the physical self. The human spirit cannot grow apart from a relationship to God and a righteous life on earth.

Not only does the spirit receive vitality elements from the physical self, it also contributes "spirit elements" to the physical self. The physical thereby reflects the spiritual. Because of this intimate relationship between the physical self and the spiritual self, a human being is in the position of mediator between the physical world and the spiritual world. The physical self consists of physical elements and exists on the physical plane, whereas the spirit consists of spiritual elements and exists on the spiritual plane. In the ideal world, a human being would exercise dominion over both realms, and would act as the center of harmony between them.

I would like to conclude my presentation of the principle of creation with one final point. As sons and daughters of God, human beings are meant to live eternally in the spiritual world. The physical self, like all other physical beings, has a finite existence; but the spiritual self continues after physical death. However, spiritual growth takes place in the context of life on earth. According to the Divine Principle, when a person dies he or she is not sent to heaven or hell. Instead, our spiritual situation after physical death is determined by the level of spiritual development we have attained while on earth. We take our vices and virtues with us, so to speak. We reap what we sow. If I want to live among the saints in the spiritual world, in close communion with God, then I am well advised to grow to that level while I am here on earth. The alternative is to grow when I am in the spiritual world by helping others who still have their physical bodies -- which means that my growth is dependent on my participation in the good deeds of others. Therefore, spiritual values should be our first priority in this life; and people who sacrifice spiritual values for the sake of physical well-being are squandering an invaluable opportunity to achieve eternal happiness.

Participant: Are we to understand such figures as Adam and Eve as abstract symbols to be used for heuristic purposes, or are they historical concrete beings?

Joe Tully: We will of course deal with this in the section on Adam and Eve, and I am sorry to have used concepts which I have not yet properly explained here. But we will explain them fully. Let me briefly say that we do believe they are actual historical and substantial beings.

Participant: In your characterization of man, you indicated that the primary characteristics were mind and body; and then you indicated that for mind there are both positive and negative secondary characteristics, and for the body there are also positive and negative secondary characteristics.

Joe Tully: That is correct. Participant: I presume that there are examples of how the positive and negative are reflected in bodies and minds.

Joe Tully: There are some examples. Again, I'd like to point out, first of all, that positive and negative are in no way supposed to connote good or bad. Yes, we believe in both the intellect and emotions. When we refer to mind we do not mean only the aspect of man that is involved in intellectual reasoning. The mind contains emotion, intellect and will. We believe that there are fundamentally active and passive aspects of the intellect, emotion and will. These aspects would be a characteristic of the positive and negative aspects of the mind. With the body the positive and negative is much easier to see. We talk about the concave parts as the negative or receptive parts and the convex parts of our body as positive parts.

Participant: You made a point of comparing Unification philosophy with oriental philosophy. You referred to the yin and yang of oriental philosophy, but you said that there were differences between the oriental concept and Unification theology. Apparently the difference is that God has character, will, heart and purpose. I'm not clear what you meant there. Can you clarify that difference? In what way is that not yin-yang philosophy?

Joe Tully: As far as I understand oriental philosophy, when it explains the nature of a being in the universe or the creation, it explains it as having the nature of yin-yang. However, our thinking is different. Oriental philosophy, it seems to me, draws a line; it doesn't go beyond yin-yang. It doesn't see any other aspect to the creation, no other fundamental principle or aspect to the ultimate nature of things. We see that all things have internal character and external form as well as the plus-minus, male-female element. This is an important point because it ultimately leads us to seek God as a being of character, as a being of heart and will and purpose as well as a principle or law that operates in things. So it ultimately leads to God being a personal God, a God with whom we are able to have a "heartistic" or emotional relationship. God is not simply a law which governs us or through which our life goes on. We see principle operating in everything, but we don't see that as the full understanding of God at all.

Our theology also differs from the oriental concept of yin-yang in that, in my judgment, oriental philosophy does not clarify the nature and the origin of evil. Often, but not always, the concept of yin-yang is presented as including the aspect of evil; although many tell me that that is not what was originally intended. We in no way include in our concept of male-female and plus-minus the consideration of good and evil as part of the original nature of things and as part of the ultimate nature of God. In making the comparison with yin-yang, I was just pointing out what seemed to be similar in relation to these polarities; I was not referring to all oriental philosophy by any means.

Participant: Is it possible for an object to take on some aspects of being subject and object?

Joe Tully: Absolutely! Yes, often. Especially as subject and object achieve a harmonious relationship, then the role of stimulation or initiation is very much interchangeable, especially on the higher planes of existence, that is, in the case of man and somewhat in animals.

Kurt Johnson: I thought that it might be helpful, since the four-position foundation is a new concept to some people, if you ran through a number of examples of the four-position foundation on all kinds of levels. The concept is so universal; if you gave just five examples from the top of your head, anything from the physical world, to the family, to governments, then people could see the universality of that model and how it is regenerated over and over in creation.

Joe Tully: Yes, I will do that. Is there another question?

Participant: You said a number of times that male-female, positive-negative are not related to good and evil. Does that mean moral good and moral evil? Or is one to be preferred over another? Do you mean that the positive is the primary analogy to which the negative should conform?

Joe Tully: No. Man and woman are just two aspects of humankind; neither one is more complete or incomplete than the other. Let me just address myself to what Kurt suggested. Here are some examples of what we would call the original four-position foundations, centered on God. I am going to focus on marriage. Man and woman enter into marriage and one result of their union is a child. We speak of this as a four-position foundation, a family four-position foundation. On the individual level, we speak of people as having both mind and body. As these two enter into a proper God-centered, give-and-take relationship, the result is a perfect man or woman. Ultimately, we speak of this as a four-position foundation. We can also speak of this in the case of the proton and electron. Subject and object enter into a give-and-take relationship, and the result is a new being, an atom. We can speak of it in political terms. In a nation there are leaders and the people. If a proper relationship is established, then you will have a unified body consisting of the leader and the people which are able to exist harmoniously, multiply and grow.

Participant: If we take democracy as the example, then each person is a subject within that form. Is that the kind of thing you were getting at?

Joe Tully: Possibly. You could look at your family that way and say that each person is subject; but actually, unless you have the subject and object relationship established you will not be able to establish a unity. You cannot have unity by having only subjects. It would be the same thing as trying to establish an atom by having all protons. You know what would happen. The protons would repel each other so that they would not be able to form a unity. The same thing would happen if you had all electrons. The point is the way in which unity is established. You need to have giving and receiving roles. But remember the earlier point that was raised, namely, that subject and object are not fixed roles.

Participant: Are we all objects to our own nation then? That is crazy.

Joe Tully: Our roles are varied. As far as the nation is a nation, we are all individual parts of that nation. I am not the nation by myself. Individually, I don't see how I can be the nation. But when we are all individually uniting together with a common purpose, then we can become a group or a nation. This will relate to what we speak of as individual purpose and whole purpose. We believe that we each have an individual purpose, direction and needs. Yet there is a bigger purpose: there is my family, my neighborhood, my town, my city, my society, each of which I am part of. My individual existence is involved in that greater whole. There is no way to do without them.

We believe that a proper system of life and growth means that the individual purpose has to be guaranteed, has to be supported. It is not right that the purpose of the whole be so dominant that individual purpose and fulfillment cannot be carried out. However, we believe that life cannot be maintained wholly by individual purpose, with no consideration for others or for the environment around us. So there has to be a harmonization of the two.

Participant: What about reincarnation?

Joe Tully: We would normally explain that in our lecture on resurrection. Briefly, we do not believe in reincarnation in the same sense that I believe you are talking about. In other words, as conception takes place, a spirit form and a physical form are created at that very moment, and a new spirit form is growing within that very body at that moment. There is no shell that is produced that some other spirit man can jump into and live again. No. We will go into more detail later.

Participant: What about extra-sensory perception? How does that relate? That is sometimes understood as being a communication between the spirit world and this world.

Joe Tully: Right. We believe that we originally had spiritual senses that went beyond the limits of our physical senses, and that by means of them we would be able to communicate in a manner different from our speaking here. We don't normally teach about that or have any distinctive understanding of it.

Participant: What about glossalalia?

Joe Tully: Speaking in tongues? Generally, we don't address ourselves to it much.

Participant: So what happens if someone has had a lot of spiritual vitality for a number of years, and then gets cantankerous in the end of his days and begins to embody vitality of another kind? What happens if that person dies in the grip of negative attitudes?

Joe Tully: Well, there are so many refinements here. There are a number of factors. First, I don't believe that if a person has generally been living under the dominion of God and with his Word that he can all of a sudden become cantankerous. I would believe that that would be contrary to what he is spiritually. It can happen, but there would have to be something that is then projected out as his anger or cantankerousness or whatever.

On the other hand, if you have been living your whole life in a way that is consistent with God's way of life, being angry or upset on one day is not going to entirely recreate your spirit form in this negative form. In other words, it develops through time and it takes time to actually form the spirit structure.

Participant: Is there some kind of element that qualifies a person as a vital spiritual being other than a moral view of how that person has acted and behaved? Are there two different criteria as to what stage you would enter into in the spirit world?

Joe Tully: I think what I first tried to explain is that it is not simply a moral judgment that takes place at that point. You are judged already by what you have created. So it is not a decision of how much of this you have or how much of that you have. You are just what you are when you go there. If you have got this much love and you have got that much cantankerousness, that is just what you are.

Participant: When you were speaking of the development of the perfect man, you indicated that that man would reach a stage at which he would never fall. Is that right? Could you say why he wouldn't fall? Some of the work going on in the theology of death and dying now talks about the final object of death and things like that. Is that what you are referring to?

Joe Tully: If I understand the second part of the question, we are not talking about the same thing. If at that moment of death you repent or you do a number of things, such a change would have some effect. However, it is not going to bring a fundamental change. It is not going to completely transform you into a good person that you were not. In other words, you don't get to be a good person by wishing to be one. You get to be one by living a good life; you have to live goodness to become that very thing.

Participant: If you reach that stage of perfection, why can't you fall?

Joe Tully: Well, you become so entirely one with God's heart, so completely sensitive to the heart, so completely one with the love of God, that any process of deviation from rightness or goodness causes the same sort of agony and pain within you as it causes within God. It is such an intense thing to deviate from goodness when we are that being.

Participant: In the ideal world or the real world?

Joe Tully: We are speaking about the ideal world, that is, the original world that God intended. That comes for each person only at the point after they've grown and become the incarnation of God's Word. It comes only at the point of spiritual maturity or perfection. Here in this world it is still possible to fall, as it was possible for Adam to do so during the period of growth.

Participant: Do the figures ninety-five percent God's responsibility, and five percent man's responsibility operate in both the ideal and the fallen worlds?

Joe Tully: Yes. I didn't mention those percentages. Nonetheless, you are correct to do so. Figuratively, we refer to our concept of man having a portion of responsibility in God's scheme of things by saying man has his five percent to do. The numbers are rather arbitrary. They are simply to show that man has a small portion in relationship to God's overall responsibility. Nonetheless, that portion of responsibility applies both in the original process and in the fallen state.

Participant: Is this figurative percentage the way you would respond to the standard question, "Isn't Unification theology a theology of works rather than grace?"

Joe Tully: Again, that is a very complex issue. I would say no, it is not fundamentally by works at all. We need God's grace very much.

Participant: My question is, is the ninety-five percent which is God's responsibility your answer to that?

Joe Tully: That's right.

Charles Barfoot: I guess I'm bothered by something that has come up here. Do you believe that one can have a spiritual destiny and still not achieve it? The woman I am writing on, I think, had a real spiritual destiny, a real call, and every time she deviated from that there was hell on earth; but she certainly wasn't a moral person in the traditional sense. I am bothered by it. For instance, if Rev. Moon turned out to be an adulterer, how could he serve any historical purpose?

Joe Tully: If you live in violation of God's Word, you cannot fulfill any good purpose God may have wished you to fulfill. This gets into the question of calling and its fulfillment or nonfulfillment. We will discuss this in the lecture on predestination. One specific example would be Moses. He was supposed to lead the people out of Egypt and into the land of Canaan. Nonetheless, we find that God says "... you shall not go there, into the land which I give to the people of Israel" (Deut. 32:52). We don't believe the change is the result of God's trickery or betrayal. We explain it as the result of Moses' violation of something which he should have been doing, a violation of some part of God's will for him.

When Darrol asked me to do this a couple of weeks ago, and said we had twenty minutes, my first thought was that my old days in preaching class were returning, so I should make one point and make it well. After listening to this morning's presentation 1 realize that the material we have to cover is extremely broad, so I'll try to make one point about something which I think is significant. At this point I am not concerned with the actual content of the dogma and doctrine that we are listening to, but with the whole context of biblical interpretation.

For me it has to begin with a quote from Barth who said our approach to sacred scripture must begin without any overt presuppositions. Or at least, Barth said, it must begin with a critical attitude towards those presuppositions.

It is my feeling (and I will make this descriptive rather than necessarily didactic or analytical) that the Unification theologian has come to scripture with a set of presuppositions. Let me describe what I mean by that. It seems to me, and I am specifically talking about the Old Testament at this point, that in the history of Old Testament interpretation there have been major paradigmatic shifts. I describe those shifts in this way: Initially the Bible was not the Bible but it was read as a group of writings with no sense of them as a canon. They were simply read as a part of the Hebrew culture. Then the major shift came when the Hebrew people began to read those writings as a scripture, as a canon, as a religious document; that was a major paradigmatic shift. They thus brought to those writings a whole different set of presuppositions of faith and cultic understanding.

Another major paradigmatic shift took place when the New Testament church brought to the Old Testament a Christian interpretation of Old Testament texts. In effect, the Christians have set up, just like the Unificationists, a principle outside the canon itself, or outside of the Old Testament canon by which we interpret the Old Testament. Often (and here I'll make a value judgment) the Christians prostituted the Old Testament texts and themes. That did and does happen.

Another paradigmatic shift came with biblical criticism. Types of criticism such as literary, historical, form, and source criticism brought presuppositions to the text. This shift has affected all of us who study the Bible professionally, and indirectly anyone who listens to a sermon or talk. Not even the strict fundamentalist is immune.

Inherent in these paradigmatic shifts is the fact that we can never go back. We cannot possibly go back to a pre-critical understanding of scripture. Certain conservative elements in the history of the Christian church have tried to do just that, but it is impossible. These paradigmatic shifts historically chronicle this tendency to bring to the text another set of suppositions by which we interpret the text. Now that is my understanding of what has happened with the Unification Church. They have adopted a set of presuppositions, elucidated and elaborated in the Divine Principle, to interpret the text. The key statement this morning was that the Divine Principle is not a commentary on the scriptures: this text was and is a revelation. This was a divine revelation: a certain body of information that helps us understand the Bible. Now what are the implications of that kind of paradigmatic shift?

The key thing is what that means we can do with language. If you have a set of suppositions or presuppositions outside the text, giving you the criteria by which you judge the text, then you are doing certain things with language.

For example, to understand the nature of God as creator or just his nature as God, we have inherent in the Old Testament text a use of language that tells us how we can interpret and understand the nature of God. In the Old Testament, God is always described with language that is highly metaphorical and analogical. It can't be anything else but that, obviously. The only way humans can communicate symbols is by means of language. Also God is described not in terms of what he is but in terms of what he does. This reveals a fundamental cleavage between how scripture describes God and how the Divine Principle describes God; each uses a different set of presuppositions. In the Old Testament God is described with metaphors such as "a rushing stream" in Isaiah 59; "he will roar like a lion" and he comes "like a bear robbed of her cubs" in Hosea; in Psalms he is like "a light." In other words, the metaphors in the Old Testament, the language of the Old Testament, are used to describe God's action. The emphasis is not necessarily or primarily on the essence of God except as it is reflected in those active ways. That is a way in which the language is used in the Bible to interpret itself, which, of course, is the great Reformation doctrine that the Bible always interprets itself. Now in the Divine Principle you see a different kind of thing happening. You see God described in his nature by the use of reasoning from science. God by his nature is positive and 'negative because we see that in his creation.

That description is something foreign to biblical language. Biblical language does not describe God in those terms. Now I am not making a value judgment about whether the Divine Principle is true or not true. I am simply saying that in speaking in scientific and philosophic terms, The Divine Principle, is not congruent with the biblical way of describing the nature of God. Coming from my tradition, the minute you take language and use it in a way foreign to its own suppositional framework, you have made a major, and violent, shift. Then you have to ask questions like "Is the Divine Principle within the Christian tradition?" For future reference, we must ask questions of hermeneutics; the questions of interpretation and meaning. They are prior to questions of dogma.

I hadn't anticipated that my debate with my colleagues would begin so early. I had intended to begin with the Apostle's Creed and the Nicean Creed, and introduce as critical for the Christian understanding of the doctrine of creation words like homoousios, creatio ex nihilo, "of one substance with the Father," a whole language that is dogmatically defide obligatory upon every Christian from the point of view at least of the Catholic tradition and surely never denied by Calvin or Luther as a proper summary of the teaching of scripture. But here my starting point has been ruled out of order as non-Christian by my colleague Roy Carlisle.

I want to say some things about the Christian doctrine of creation. First, we believe that God is Father, creator of heaven and earth and of all things visible and invisible. We believe about God that God is Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Yet we didn't hear anything this morning about God as Father. Now I know as do most of you that within Unification theology, God's essential character as Father is stressed. Yet we only heard peripherally this morning about God as Father. Why? Here I think my colleague Roy Carlisle is pointing out something very specific. Namely, that there is a certain pseudo-scientism that is being offered to us as a kind of prolegomena before they get around to what they really want to say, namely, that God is Father. But if that is what they really want to say, then shouldn't they say it first? Now this is just a minor point on procedure, but central to the Unification understanding of God. Here one moves directly from an understanding of human life within the family-parent-child relationship as they call it -- to knowledge of God. From this natural knowledge we can move to understand the heart of God. I want to mention that first as a point where Christian faith and Unification theology have a great deal in common. However, that commonality didn't come out this morning.

Secondly, within Christian theology it is said that the opera ad extra of the Trinity are indivisible though God is one in three persons. Yet, terra propriatione, by the proprieties of language, we can say that God's creative activity is really an expression of God's fatherhood. Creation is like the act of a father bringing whatever a father brings into existence into existence. Now is it thought within Christian theology that the world that God creates stands in relation to God as something like a child? This is something that it seems to me has never been adequately explored within Christian theology. The reason is. I believe. this: when, within Christian theology in the early years of the church, there was speculation about whether or not the world might exist in relation to God as progeny or child, there arose a very serious problem, namely, that we want to say something about the character of Jesus as the only true and perfect child of God and therefore we can't say those kinds of things about the world. Also, as you know, in the early period of the church, the world was in fact perceived as material hence less godly than God ought to be. Consequently, in relation to this problem, the church taught the third point -- a point where we may have some interesting differences between Christianity and Unification theology -- creatio ex nihilo, that the world is created by God, not from something else. Some people say ex nihilo, but that isn't the proper way to say it because of ex nihilo nihil est, nothing comes from nothing. The correct doctrine is ex nihilo per deum, God from nothing at all creates the world through the power of God. Now some Christians obviously think that the world is created by God out of nothing. But nothing could be more nonsense, for the reason just stated. Christians, I believe, teach that God created the world out of nothing more than his own sovereign power and life. Now this is in fact very close to the Unification Church. And why did the church teach this? It taught this because it wanted to say that the world is good and as good as the power of God can make the world to be. I mean the affirmation of the goodness of the world is the motivation behind the doctrine of creatio ex nihilo. It seems to me that on this point, if I may say, Unification theology though it teaches a certain immanationism, is in line with the intentionality of Christian theology. The world does in a sense, come from God, understood as a Father whose own being flows before himself. Indeed, it even seems to me to be vindicated in terms of the doctrinal niceties.

I have mentioned three points. I just want to review them quickly. I found that the biggest defect in the presentation this morning was the putting of what seems to me to be the essential teaching of the Unification theology away from the center of the discussion. Consequently, the doctrine of creation was presented without talking about God as Father and talking about the creation as that act which most appropriately expresses the heart and the will of God. This, it seems to me, is a very disturbing thing. Why is it that the Divine Principle is being presented in a way that obscures from the hearer the true intentionality of the theology, namely, that the creation is an expression of the fatherly heart of God. That is, it seems to me, a very critical question that points to a serious failure in the presentation -- not the content -- of the theology.

My fourth point concerns the doctrine of the imago dei that we heard today. What is the doctrine of the imago dei in Christian theology? Christians teach that God is Father, Son and Holy Spirit, one and indivisible. But creation is most appropriately related to the Father. Creation is purely an expression of God's sovereign power. But Christians say that God creates the world in his own image. Now let us consider this for a moment. Do we mean that the whole world is created in the image of God? Or do we just mean man is created in the image of God? The Greeks say that man is the microcosm of the macrocosm, consequently the whole world exists in the image of man who is created in the image of God. In some way, then, the whole world is created in the image of God. Now this, it seems to me, is in fact Unification theology's position. But the point at which it seems to me that Unification theology is offering an important suggestion -- one with which I am inclined to agree, by the way, because it seems to me to be more truly scriptural -- concerns how we should conceive the character of that image. In the Unification view it should not be conceived in terms of Greek categories of rationality and freedom or in terms of the differences between man and animals. Nor should it be conceived along lines of the Reformation tendency to talk about the image of God as man mirroring back to God God's own characteristics while lacking them substantially himself. The suggestion of Unification theology is that we conceive the imago dei as man as co-creator. We all know that every group tends to believe that their ideas are a little more novel than they really are and that is true here as well. The suggestion that the imago dei is man as co-creator is also in my Calvinist tradition where man's co-creativity is understood to be the very point of the imago dei. The grounding of this doctrine in Calvinism is the scriptural text wherein man is created on the sixth day to have sovereignty over all the world, participating in or imaging thereby God's own sovereignty.

In Unification teaching I would be inclined to think that the foundation in scripture for the third blessing -- have dominion -- is the scriptural account of the six days of creation. Here man is created last, not merely as sinos but as telos of creation, as the purpose of creation. It is said that by exercising dominion over the world, a man can have in-his own responsibility and life a share in and an imaging of God's own dominion of the world. I think that is a point that has been argued many times within the Christian tradition. I happen to think that it is a viable and correct interpretation of the imago dei. And now it is appearing again in Unification theology.

Earlier someone suggested that co-creativity might be related to the Reformation debate over salvation by faith or works. I don't think that a doctrine of co-creativity is related to that at all. Within this theology, it seems to me, that it is related to the determination of the character of man within the creation, realizing the image of God within himself by becoming one who shares the dominion with God over the world. God has created man for that. Since the true character of God's own creativity is fatherhood or parenthood, then the true character of man and woman exercising dominion over the world is also going to be through their parenthood. This is why the form of human family life and parenthood is so crucial to the realization of the imago dei. Now one of the interesting things about Unification theology is precisely the notion

that the imago dei is not something which is complete in the moment of creation, but rather something man must realize within himself by developing the capacity to exercise freedom, love and parenthood. God's purpose, we might say, is to bring his child into a state where the child might also be a parent and a co-creator. This is a time process.

Is this consistent with the Christian view of creation that creation is something which is fulfilled within a time process? I think it is scriptural. Moreover, it is consistent with our talk about historical time having a meaning, a purpose and a fulfillment. Hence this doctrine is consistent with the teaching of scripture and what we know about human life. The idea of the imago dei as co-creatorship and learning to love as God loves -- as a parent -- is, it seems to me, quite consistent with scripture and with the Christian dogmas on this point.

Now concerning the "real" Adam and Eve, I want to make a case for a particular view of the matter. I know the "real" Adam and Eve didn't come up in Mr. Tully's presentation this morning at any great length although the question was raised. Now within the Christian doctrine of creation there is a real Adam and Eve. I wanted to make an appeal to my sophisticated colleagues who don't believe in real Adams and Eves to think a minute about what the purpose of the argument for a real Adam and Eve is, why in fact a defense of a real Adam and Eve is so important within Unification theology. It is related to what Karl Rohner, calls monogenism: does the human race have a single origin, or does the human race have many different origins? And if the human race has many different origins then isn't it right that blacks and whites and yellows and all these peoples of all these different colors should be kept separate from one another? Don't they all really have different ancestors and shouldn't we keep them from becoming mongrelized? Within scripture the doctrine that the human race has a single ancestor is related to the belief that we are all one race, that separate races and the animosity among various races are themselves an expression of our fallen condition. Now I don't want particularly to defend an historical Adam and Eve, but I do want to raise the question among theologians of how if we are not going to defend an historical Adam and Eve are we going to defend the integrity of the human race? How can we argue as Rev. Moon argues for the importance of building one human race? Within Unification theology I would argue that systematically the reason why the doctrine of Adam and Eve is held so tenaciously is precisely because in the doctrine of restoration the same tenacious affirmation about the importance of overcoming racism is made. Thus, we must take care that we not judge the doctrine without seeing its true intention and systematic consequences.

My next point concerns the four-position foundation. I think that the four-position foundation is in fact a very helpful way of putting some kind of philosophical conceptuality on what is affirmed both in Genesis and in the New Testament. Now I don't want to use the Genesis example of "God created man, male and female created he them" because we run into problems with feminism there. I frankly think that God created us all complete. I tend to think that male and female get a little bit overdone in our society. But I want to show you where in fact there is a textual foundation within Christianity for the four-position foundation. It is at the point where they said to Jesus, "Master give us the word." and he said, linking two separate texts from the Old Testament, "... thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart and... soul, and... Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself." (Mk 12:30-31 KJV) We hear over and over again that this is the central Christian teaching. But why is that teaching so radical and significant? It's for this reason. Kierkegaard along with others has said that purity of heart is to will one thing. (Consequently, Kierkegaard gave up his fiancée believing that was true love.) We have the religious tradition that goes down through all history saying that purity of heart is to will one thing. We have St. Augustine confessing to us that he cried when his friend died. It was, he believed, terrible that he would do that because it showed that he didn't love God. he loved his friend too. Augustine loved two things. Now there is within Christianity and within other religious traditions a certain false spirituality which believes that true love is to love one thing. But Jesus said that purity of heart was not to will or love one thing. If you love just one thing, God, then you are not loving properly. Purity of heart and true love always require that you love at least two things: your God and your neighbor. This is true no matter who you are. The "love one thing" spirituality tends to result in seeking to love God but neglecting the neighbor or to loving the neighbor and neglecting God. It leads either to spiritualistic religions or to atheistic humanitarianisms, the options that constitute the two major alternatives today. To this Jesus says no! Full and true love requires that we orient ourselves within the four-position foundation: there is you, there is your neighbor, and there is your God, and then there is the purpose for which this unity exists, the common purpose. And it seems to me that the four-position foundation is in fact a helpful way of orientating people. Christian people and non-Christian people, to realize that their position in life, if they are to love truly, requires that they look at least two ways and if they look at least two ways, then their love will be productive. The four-position foundation is, it seems to me, a help here and falls within the Christian orientation though Christianity has not done particularly well on this point.

Next: it seems to me that Unification theology introduces a very interesting and helpful corrective into contemporary theology. What is a corrective? Unification theology begins talking about theology with a doctrine of creation. Now you know that if we theologians were present at any other theological conference at all we would have begun somewhere else. We would have begun with eschatology, or we would have begun with the doctrine of time and history. Here we are beginning with creation and with God's purpose for creation. It seems to me that that is where scripture begins and it seems to me, if I may make this appeal, that that is where theology should begin. Why should theology begin with a doctrine of creation instead of with christology or with the doctrine of sin? It is because beginning with creation gives theology its proper perspective on all other doctrines. Here I want to remind us of the point that was made by St. Athanasius when asking why we know that Jesus is the son of God. St. Athanasius said that the formal answer is that the Messiah must, if he is to be divine, have as the purpose of his life the same purpose as God himself. If the purpose of the Messiah is any less than the purpose of God himself then in his work at least he falls short of divinity. Jesus has to have the same purpose as God in creation, says Athanasius, if Jesus is to be son of God. Now unless you begin a theology with the doctrine of creation, you can't have a proper doctrine of the deity of Jesus Christ and you can't have a proper doctrine of the messiah at all. And so it seems to me that Unification theology by beginning here is restoring Christianity to a true understanding of its Messiah, Jesus Christ. It is an understanding of the messianic task in relation to a number of alternative proposals about what the messianic work is. Much as I love liberation theology and theology of play and this and that, I don't think any of those activities, good as they are for human beings, are all that is required to be divine.

Now my last point. It is the best one. I am going to tell you why it is the case that Unification theology, or better, Rev. Moon, has raised and in fact offered a solution to a theological question that has never been raised within orthodox Christian theology and therefore has never been answered. This is related to the doctrine of creation though it is not adequately treated at this point. The problem is this: in the Old Testament, although the messiah is anticipated, it is never anticipated that the messiah when he comes will be God's own son. In the Old Testament the messiah is anticipated as king, prophet, as son of manias an angelic being, under various kinds of symbols, but never as God's own son. When Jesus comes fulfilling the messianic task he proclaims himself as God's own son and is recognized by the church as such. Here is the question, why did the messianic task have to be fulfilled by one who was God's own son? The Old Testament doesn't anticipate that the messianic task is going to have to be fulfilled by God's own son. Something novel happens here. Why did the messianic task have to be fulfilled by one who is God's own son? And that is the question to which Rev. Moon is suggesting an answer. Now I think this is a good theological question for Christian theologians to discuss with Unification theologians. I think that it could lead us into very fruitful further debate.

It is fruitful to start at the point to which Roy Carlisle has brought us: i.e., attention to presuppositions which inform our explication of the Christian revelation and our philosophico-theological reflection on Christian beliefs concerning reality, and man, and the relation between them. Of course, any thinker will have presuppositions. And it is a truism to say that even the view that one ought to approach scripture and reflection about Christian beliefs without presuppositions itself has a number of presuppositions: i.e., that this enterprise is possible; that is, is desirable; and that one can always become aware of one's presuppositions and successfully expunge them from one's inquiry. Some of us remember that a decade ago the "new theologians" advised us to accept no interpretation of scripture which was not compatible with current scientific conclusions. This is a prime example of the epistemological status of many presuppositions which inform religious thought: e.g., it was initially unclear and never sufficiently clarified; the reinterpretations of Christian beliefs to which it gave rise were declared rather than submitted to the Christian for assessment; and the relations between revelation and science were not adequately explored. Why, for example, should the science of any particular day provide the limits within which scripture must be interpreted?

Certainly in our philosophico-theological work it is a desideratum to become aware of our presuppositions. This is, of course, not always an easy task. I have tried to become aware of what I am assuming in this response, and I will mention some of my presuppositions. These are, by the way, presuppositions only relative to this context. I can examine them and have done so. They are not intended to be a priori.

First, I presuppose that ideally the individual's mode of interpretation of his life's experiences is informed by his metaphysico-religious commitment; that these experiences provide opportunity for assessment of his commitment; and that what he learns from these experiences he does not legitimately leave out of his philosophico-reflection. Widespread today, however, is the view expressed by a professional colleague at a conference on theological topics. He confessed to a Christian commitment but then added, "I do not let my religious views have any effect on my philosophical inquiry." There is also another point of view on this topic, one which was never challenged in classical Chinese and Indian thought and which in the West is certainly as old as Socrates and Plato and very likely to be found in the teaching of Pythagoras. This is the view that whatever the thinker's areas of inquiry, he may never turn away from any opportunity to assess and develop his hypotheses and verify his conclusions in experience. This is my presupposition, too; and in what I am going to say about the principle of creation in Unification thought, I draw upon my experience with its tenets.

Second, I presuppose that we are on the verge of a new day in philosophical thought which will bring what probably will be seen (by those prepared to comprehend the true magnitude of events in the philosophical community) as the most tremendous philosophical creativity the world has ever known and which will break through the limits imposed artificially and dogmatically on philosophical thought during the past century. I have grounds for this presupposition. Thus, there has been a progression in twentieth century American and British philosophy from the very stringent limitations imposed by logical empiricism through the greater generosity of instrumentalism toward the de facto range of human concerns and ending now in phenomenology and existentialism to which, it may properly be said, that nothing human is foreign. Each of these views is an important contribution to contemporary philosophy. But even taken all together they are not sufficient. For accompanying the increase in generosity toward human affairs, there has also been a progression toward a more thoroughgoing enclosing us in our human condition. The lack of self-consciousness properly associated with spiritual maturity and essential to the willingness to lose one's life to find it as required by Christianity becomes impossible with the latest philosophical developments. We need the philosophical creativity which will lead us out of this.

Third, I presuppose that this new day in philosophical creativity will move in the direction of establishing a worldwide philosophical community in which the many philosophical perspectives on man and reality will each be recognized as contributing something of value To the new philosophical ecumenism. Further, this ecumenism must salvage and develop ancient concepts and beliefs which are necessary today but which have not had sufficient attention in recent years when both philosophical and theological communities have been primarily interested in "that which has never been said heretofore," regardless of how destructive these novel ideas might be.

These three presuppositions have determined my response to this morning's presentation of the principle of creation as set forth in the Divine Principle. I want to say initially, however, that when I first read this book I immediately felt at home. Without realizing it. I had been thinking along Unification lines during all my professional life. In my opinion the Divine Principle is, as David Kim said last night, an uncut jewel; and as such it is a major contribution to present philosophical and theological thought. In particular I want to stress these things.

The Divine Principle draws our attention to many ancient philosophical, religious concepts which are of the highest significance. One of these is "man is the microcosm" and its correlative "man is the measure of all things" as interpreted, of course, by Plato rather than by Protagoras. These dicta are promising today because they may become the basis of a response to the view that man is alienated from reality which, as I indicated above, has been widely accepted in twentieth-century thought. To be sure, they will need to be newly developed before the philosophical community can be persuaded of their metaphysical, epistemological and axiological content and import. The Divine Principle, however, may be interpreted as making just that suggestion.

Another ancient view common to both East and West which the Divine Principle restores to philosophical thought is the teaching that all inquiry, whether in history, science, philosophy or religion, can be adequately carried on only by the person possessing the proper holistic development. The Unification word heartistic draws attention to the valuational, humanistic, and affective dimensions of holistic development. Further, I take this Unification view of holistic development to be in our day a return to Plato's view of the role of the just man in inquiry and in practice, The effects of our long neglect of spiritual, humane, and moral considerations in technology and in our approach to nature are evidence of our need to listen once more to what Plato had to say about holistic development.

The Divine Principle throughout is not only asking for, but predicting the development of a worldwide philosophical community. There are recurring references to the permanent importance of the teachings of some of the great world religions, notably Taoism, Buddhism, and Hinduism. To be sure, these references are only suggestive, and by no means complete. Yet these suggestions can become the basis for this important work. Outside of Unification thought the work of building a world philosophical community is certainly going on. It is, however, going on very slowly and without sufficient attention to the very important irreducible differences among Western and Eastern views of man and reality. This danger, I think, is remedied in the suggestions of the Divine Principle, which may be interpreted as a warning not to overlook these differences.

Finally, last night David Kim and this morning Joe Tully brought to our attention two very important ancient concepts which I have never before heard discussed in any academic milieu. One is the ineluctable role of numbers in the flux of human affairs. Lao-tzu told us, "The one begets the two and the two begets the three." We may, of course, interpret this superficially; but surely we need not. Perhaps this Taoist insight needs to be studied in connection with the Judeo-Christian use of numbers, of which the Catholic novena is an example. Joe Tully summed it up when he said that, although the mathematically structured flux may look like an accident, it really is a process being worked through. And David Kim called our attention to indemnity which is a new emphasis on what throughout the history of religion is known as sacrifice and which in the Christian tradition is known as intercession. Surely, it is of the highest significance if one person or group of persons can fulfill the claims that divine justice makes on another person or group. And surely it is also of the highest significance if we can accomplish through indemnity what others either cannot or will not achieve for themselves. In introducing this concept into philosophical thought, the Divine Principle has done us all no small service.

There is, however, one issue -- and perhaps only one -- where I have to back off from Unification teaching on the principle of creation. This is the Unification denial of the divinity of Christ, as it has been traditionally interpreted by the church. My own belief in this ancient Christian teaching, together with the literal interpretation of the virgin birth, the resurrection, and the ascension is for me a major achievement. This is a belief that affects all aspects of my life. So when I speak in defense of it I am -- in accordance with my presuppositions -- drawing upon my experiences. The four-position foundation illumines these experiences.

In particular, the four-position foundation in relation to natural beauty is a help here. At the top of the four-position foundation is God. As steward of creation, under God, I am subject in relation to natural beauty -- e.g., bird songs, sky and clouds, and the wonder and whimsy of animals -- which is object. Now if I am responsive to natural beauty, then I am also in the object position and the beauty of nature is in the subject position. That is, I learn from natural beauty. And then a fourth thing is, indeed, created: i.e., a new spirit within me, new insight which arises from my caring for and response to natural beauty that man has not made and which, although we can ruin it, foster it, or cultivate it, is not human art. What I have learned from Augustine, Francis of Assisi, and Bonaventura, as well as many others, is that in natural beauty I find the logos, who is divine, who became man, and who is Jesus Christ, the Redeemer. That is the greatest thing I know.

Don Jones: I would like the panel to respond to what I think is a clear-cut difference between Herbert Richardson and Mary Rose: Rose's preference for the Greek Platonic mode of discourse and Richardson's preference for the Hebraic dramatic and historical discourse. Do you have a preference for your own mode of discourse and means of expressing your faith? Is it with Mary or is it with Roy and Herb?

Anthony Guerra: I would say that both of those modes are certainly present within the text of the Divine Principle. Both the Hebraic and Hellenic, or, if you will, the mythic and the discursive modes are present there. I think it is healthy to maintain both modes and I find at various times the use of one or the other to be more appropriate. I would suggest, for instance, that it is very important for communicating with most of the secular world to use a discursive mode and to have a kind of natural theological perspective which is pretty much what was presented this morning. This serves as a kind of prolegomenon to speaking about God as parent. In my experience of presenting the Divine Principle, that was the most effective way to reach the deeper spiritual points, and therefore I would prefer not to choose between either mode.

Paul Sharkey: I would like to ask a question about that because what I hear you saying is that perhaps the discursive mode is heuristic. 1 think that there is something in the original question about which is preferred. It sounded to me as though you were saying that you found the use of a natural theology to be a means of getting to the deeper spiritual modes. Do you in fact see all this stuff as basically heuristic, as a means of getting to a deeper truth, or do you take the natural theology or metaphysics more literally?

Anthony Guerra: Again I would say that it is in a sense a prolegomenon. One uses the discursive mode -- one might say both the ontological mode and the existential mode -- in speaking about reality. Whether or not it is heuristic involves the question of what is the relationship between a language and reality or truth? Is it best got at by the discursive mode alone? I think that it is not. That is one perspective by which one perceives what is. But multiple perspectives, especially these two traditional ways, are valid. As to the relationship of those two modes, I must say that I think that within each thinker, within each individual, they are in dialogue. One doesn't think only inductively or only deductively, but one uses both modes of thinking. These, together with others, lead to a certain world view. What we are being presented with is, in one sense, a world view. Several modes of thinking contribute to its construction. I would put it that way.

Darrol Bryant: I think there are two ways of asking this question: you might ask it in terms of the modes of discourse, or you might ask (and I suspect that Professor Sharkey means this) if when you use the language of metaphysics you are telling us something true about reality. Is that language to be taken seriously at that level? Or, is metaphysical language just a device to open the way for saying something later? When, for example, we talk about God's fatherhood, how is that language to be understood? Are we to understand that quite literally? It seems to me that is where some of the confusion and some of the questions that are being raised here come from.

Stanley Johannesen: As a matter of fact, when you come to the fall and you talk about Satan having actual sexual intercourse with Eve, that is a mode of discourse that certainly seems different from Joe's presentation this morning. Why is creation, then, not a dramatic personal act of the father who may in fact be a grandfather? What is wrong with that language? When you get to the fall, you don't hesitate to use that kind of mythological or factual or dramatic language.

Joe Tully: I think I'll probably be responding to a couple of people here. It seems to me that what you are asking is whether or not there is some motive for choosing a certain way of expressing things. I don't think that there is any particular motive that I am aware of for speaking in one manner or another. That is why I pretty much agree with what Anthony said in his first answer: we can speak comfortably in either mode.

One other thing -- I find it interesting that both Roy Carlisle and Dr. Richardson commented on the use of the concepts of positive and negative as some sort of attempt to be scientific. Frankly, I have never thought of that reason for talking about positive or negative. Either positive and negative, male and female are part of reality or they are not. We are simply using terms to describe what is out there. The fact that they were discovered through science, or only called positive and negative by science, is not at all our reason for using them. I feel comfortable discussing the whole thing in any kind of terms you would like. This is simply how we have expressed it. Does that get at what you have been asking or not?

Darrol Bryant: I think that raises a whole new set of problems which is evidenced by the fact that all of a sudden there are several people who want to make comments.

Thomas Boslooper: I was just going to comment that maybe one reason that the Unification people use one kind of language for creation and another kind of language for the fall is because the Bible uses two kinds of languages. The language of Genesis 1 is different from the language of Genesis 2 and 3.

Tom McGowan: One of the problems I'm having -- and I have frequently dialogued about this with Unificationists -- is this eclecticism. I have experienced it theologically and I am experiencing it right now philosophically. People up and say "I don't care which philosophical discourse I use; I am comfortable in both." That makes me uncomfortable. The problem comes up especially with the question of evil. One answer to the problem of evil is Satan; so we have that kind of language. But then, this morning Joe Tully spoke about evil in terms of a process of growth, giving us a whole new idea of evil as frustration at not reaching perfection. Maybe creation is still going on and we are still perfecting ourselves. This would be similar to the Mormon concept of ongoing creation or Teilhard de Chardin's view of a universe moving Towards Christ. But the problem is that we have these two definitions of evil being used, and I find it frustrating when Unification theology neatly moves from one to the other.