4 Epistemology

Many philosophers have developed epistemologies based upon their philosophical viewpoints. Although we have natural sciences for the study of the material world and the Unification Principle for the study of the philosophical world, we must, nonetheless, formulate a Unification Epistemology to clarify our standpoint on human knowledge and cognition and to point out the inadequacies of the epistemologies presented in the past.

The epistemology derived from communist philosophy is based on the theory of reflection (teoriya otrazhenia), which is a philosophical means for justifying violent revolution. Besides dealing with cognition of natural phenomena, it is closely connected with practice and with politics. It deals also with non-political practices, such as scientific research and the manufacturing of goods, but these are relegated to mere expediency. The key-point in this theory is to have people dearly perceive the faults and contradictions of the capitalist system, in order to overthrow it. Unification Epistemology must point out the errors and defects of this theory. Furthermore, it must present a viable explanation that testifies to the authority of the Unification Principle, from which it is derived.

I. Traditional Epistemologies

A. The Source of Cognition

What is the source of cognition? A cognition is attained by the mutual interaction between the mind of man, which is subject, and the objective world. The objective world cannot be recognized by man’s mind directly, but must first be perceived by man’s senses, which relate directly to the objective world. We can say there is a flower in the objective world when we experience it with our senses. Seeing a flower means perceiving it through the sense of sight. Where exactly does the process of cognition take place? In man’s sensual stage? Or does it take place in the deeper stage of understanding, or even in that of reason? Two schools of thought have contended with each other over this matter: the school of empiricism and that of rationalism.

1. Empiricism

Francis Bacon said that truth can be acquired by experiments and observations—i.e., by experiences. His successor, John Locke, established a branch of philosophy called Empiricism, which says that experiences, rather than reason, are the source of our cognitions. In his book, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Locke said that man’s innate mind, or mind at birth, is like blank paper (tabula rasa) or like a dark room. Knowledge is the experience that is imprinted on it from the outside, just like a picture that is imprinted on white paper.

A dark room needs windows for light to enter; our mind needs windows through which knowledge can enter. There are two windows: sensation (physical senses) and reflection (internal sense). Sensation functions to form ideas from external experiences, through which we can perceive physical qualities-such as yellow, white, hot, cold, soft, hard, bitter, and sweet. Reflection functions to form ideas from internal experiences, through which we can know the operations of our mind-such as perception, thinking, doubting, believing, reasoning, knowing, and willing.

Simple ideas are formed involuntarily through sensation and reflection. In the perception of a flower, for example, each element of the sensation (color, shape, aroma, etc.) is carried to the brain, where it forms a simple idea. The sensations are fragmented, since they come via diffe rent en e organs—the eyes, the nose, the ear, etc. Complex ideas are formed through the activity of the mind, which combines or associates simple ideas.

There are two kinds of qualities in simple ideas: primary qualities and secondary qualities. Ideas of figure, extension, motion, solidity, number, and so on, are primary qualities; the ideas of color, sound, odor, taste, temperature, and so on, are secondary qualities. The cognition of primary qualities is objective and does not vary from person to person. The cognition of secondary qualities is subjective and varies from per on to per on. If two people look at the ame object, both will perceive the object as having the same hape bur one may see it as a deep-colored object, while the other perceives it as a light-colored object.

Man’s mind has the ability co associate simple ideas thus forming complex ideas. The idea of ‘gold’, for instance, is obtained from the as ociation of the simple idea of color, weight, hardness, ductility, and fusibility. The idea of gold, therefore, is a complex idea. One acquires imple idea from external experiences and obtains knowledge through associating simple idea . This is the main point of Locke’s empiricism, which influenced Berkeley and Hume.

2. Rationalism

As a method for his philosophical investigations, Descartes doubted the existence of the physical objects around him, allowing for the possibility that our senses may deceive us, or that everything we have in our minds is nothing but illusion and dreams. One thing could not be doubted: the fact that he was doubting. Hence the famous proposition, “I think, therefore I am” (Cogito, ergo sum) was set up. Descartes thought this proposition certain because it was ‘clear and distinct’; thus, it became the first principle of his philosophy.

From this first principle he derived the general rule, “Everything that we conceive very clearly and distinctly is true.” The opposite to ‘clear and distinct’ is ‘confused and obscure’; ideas that contain something ‘confused and obscure’ contain falsity.

Consequently, my existence is certain. I am nothing more than a thing that thinks: I am reason. Reason is the judgment of truth. If a certain knowledge or cognition is clear and distinct in my reason, it is true. Since matter appears to be clear and distinct in my mind, its existence is certain. Here another proposition is established as certain: “Matter exits.” There are two substances: the thinking substance (mind) and the extended substance (matter). According to Descartes these two substances are entirely independent of each other. They are, however, both dependent on God—the only independent entity—and through Him they can relate to each other.

The point of Descartes’s rationalism is that we have true knowledge or true cognition if reason judges it to be clear and distinct. If it is not approved by reason, it cannot be true. In this philo ophy reason is the source of cognition.

B. The Essence of the Object of Cognition

Other questions to be investigated in Epistemology are: What is the essence of the object of cognition? Does the object of cognition really exist in the objective world independently of the ubject, or does it merely exist in the mind of the subject (man) as an idea?

1. Realism

Realism says the object of cognition does exist in the objective world.

Naive realism is the view that the object of cognition is the material being as we perceive it to be. A great number of people may be included in this category.

In scientific realism on the other hand, scientists come to certain conclusions from experiments, but going beyond simply a cepting the results of the experiments, they reflect upon them. When Isaac Newton saw an apple fall, he reflected upon it and concluded inductively that everything is subject to the force of gravitation. This type of realism is characterized by scientific reflection.

In contrast, realistic idealism and objective idealism say that it is not matter, but idea, that exists independently of the subject. Plato and Hegel are representatives of this trend. According to Plato idea appears in the phenomenal world garbed in the robes of matter; it is the primary existence in the phenomenal world. For Hegel, the phenomenal world (nature) is the Idea (Idee) in the form of otherness. The essence of the phenomenal world is Idea, or Reason—not matter.

Communists advance the ‘theory of reflection’ or ‘copy theory’ (teoriya otrazhenia) to explain the process of cognition. According to this theory, objects can be reflected in man’s brain, just as they are reflected in a mirror. Lenin pointed out that the process of cognizing does not end with reflections, but must continue through practice, for it is through practice that one verifies what has been reflected. This view is a kind of realism, since it emphasizes that matter exists outside the subject. Communists however, do not usually call it realism, in order to avoid confusion with ideal realism, such as that proposed by Plato. The communist view is commonly referred to as dialectical epistemology or theory of reflection.

2. Subjective Idealism

Contrary to realism, subjective idealism says that nothing exists outside, or independently of, the subject. Whereas Plato and Hegel recognize the existence of the idea outside man’s mind, Berkeley, for instance, maintains that all things exist in the mind of man as ideas. In other words, the object of cognition is the idea within the subject. This is known as subjective idealism, or immaterialism. Berkeley’s basic principle is “to be is to be perceived” (esse est percipi), implying that although things seem to exist outside the mind, they cannot actually exist except as perceived by the mind. He was suspicious of Locke’s empiricism, arguing that Locke’s theory would lead to skepticism. According to Locke, the primary qualities (extension, speed, solidity, etc.) are objective, whereas secondary qualities (heat, color, sound, etc.) are subjective. Berkeley said that even the primary qualities are subjective, for they are intimately connected with the secondary qualities; if the secondary qualities cannot exist without the mind, neither can the primary qualities. The image of distance, for example, which seems to be independent of the observer, is actually subjective. Suppose there is a flower in front of you. You walk towards it step by step. On your twentieth step you reach it. At that point you can recognize the original distance through the tactile sensation of walking twenty steps. Seeing the flower with your eyes, also, is a sensation. According to Berkeley, the image of distance is the synthesis of these various sensations. Distance, therefore, does not really exist in the objective world; it is only suggested by our experience.

Distance, however, does exist in the objective world, we hold. We can sense it when we observe things with both eyes (although not so well when using only one eye). When looking at an object with both of our eyes, there is an angle formed by the two lines that can be drawn between the object and each eye. This angle is wide when the object is near, and narrow when the object is far away. Through this angle our mind can judge distance, which can be said to exist objectively, since the angle itself exists objectively. This is one of the ways we can recognize distance; Berkeley, however, probably lacked this information. Thus, flaws can be pointed out in subjective idealism, even through scientific means.

Locke’s empiricism became skepticism when it reached Hume through Berkeley. Hume said that every experience is subjective; the relationship of cause and effect cannot be ascertained directly from our experiences. In a thunderstorm, for instance, first we see the lightning, then we hear the thunderclap. The conclusion that the relationship between the lightnjng and the thunderclap is that of cause and effect is purely subjective. When we say that two phenomena are connected by the relationship of cause and effect, what we actually experience is that those phenomena are connected by the relationship of before and after. There is nothing in our experience to indicate a necessary connection.

For example, we have experienced numerous times that the sun rises soon after the cock crows. Yet people know there is no cause-and-effect relationship there. Why, then, should we ascribe a cause-and-effect relationship to lightning and thunder? Based on this analysis, Hume expressed his skepticism about the so-called law of cause and effect.

The weak point in Hume’s philosophy is that he did not consider practice in his approach to cognition. According to the Unification Thought view, cognition must have give-and-take action with practice, for it is not conclusory in itself. In the example above, we can create thunder-like phenomena through an electrical discharge experiment. The relationship of cause and effect, then, is not concluded solely by cognition, but also by practice. In Unification Thought, therefore, we need not fall into skepticism.

C. The Method of Cognition

1. Kant’s Transcendental Method

Kant attempted to unify continental Rationalism and British Empiricism. He also tried to establish epistemology as a philosophical base for the natural sciences, which by that time had developed considerably.

British empiricism had fallen into skepticism, and continental rationalism had become dogmatic. In Kant’s opinion, rationalism had become dogmatic because continental philosophers had established their theories without sufficient re-examination. He maintained that theories should be established by accurate and rigorous analytical (critical) methods, and not dogmatically.

Kant argues that we must examine the possibility and authenticity of man’s cognition. Locke has no problems here, since he says that the cognition is, in fact, the experience. Probing even further, however, one can ask, “how is experience itself possible?” “How can ideas (such as Locke’s simple and complex ideas) be formed in our mind?”

Kant’s approach, called Critical Philosophy, consists of three critiques, formulated in his later years: the Critique of Pure Reason, the Critique of Practical Reason, and the Critique of Judgment. The Critique of Pure Reason analyzes the process of cognizing, so I will discuss it briefly.

Since cognition is nothing more than judgment, the problems of cognition are the problems of judgment. (Kant inquired about the possiblity of judgment, not the possibility of cognition.)

Judgment is a proposition; it necessarily consists of a subject and a predicate. Its form is “…is...” —such as “This flower is beautiful,” where ‘flower’ is the subject and ‘is beautiful’ is the predicate. In Kant’s view, judgments are either analytic or synthetic. In analytic judgment, the subject already contains the meaning of the predicate; in synthetic judgment, the subject receives new meaning from the predicate. One cannot acquire new knowledge through analytic judgments. Take, for example, Deseartes’s proposition, “All things have extension.” (‘Extension’ here means size, length, thickness, etc.) The term ‘all things’ is the subject, while ‘have extension’ is the predicate. Things, however, already contain the idea of size, length, and thickness; in other words, things already contain the idea of extension. That is an analytic judgment.

On the other hand, in the proposition “This chalk is red,” the subject ‘chalk’ does not contain the idea of ‘red’. Although a chalk always contains extension, it does not contain any definite color, for it can be red, white, or some other color. Here, the subject acquires new meaning (the color red) because of the predicate. Consequently, this is a synthetic judgment, through which new knowledge is acquired. It is through synthetic judgments that the progress of science takes place, Kant maintains. Newton, for instance, discovered that all things have gravitation. It was revolutionary new knowledge; though all things were supposed to have extension, figure, weight, and so on, gravitation was unknown then. Man’s knowledge increased, and science progressed, as a result of that synthetic judgment.

In order for a synthetic judgment to be true, it must be universal—i.e., valid not just for some people, but for all people, regardless of place and age. In order to be universal, however, a judgment must be ‘a priori’, (prior to experience); in other words, it must be effected through the use of a priori forms of synthesis (categories).

The terms categories (Kategorien), forms of synthesis, pure concepts of understanding (reiner Verstandesbegriff) and thinking forms (Denkformen) refer to a way of thinking, a restriction of thinking, or a frame of thinking. When we see an object, we ask ‘what’ it is; when we see something move, we say that ‘something’ moves. Thus, we tend to think of an occurence in relation to the subject (substance); we tend to think that ‘something’ has caused the occurrence. This form is called Substance (Substanz).

Another form is Causality (Kausalität): we tend to see successive phenomena in a cause-effect relationship. Reality (Realität) and Negation (Negation) are forms as well; we have a tendency to query whether or not something really exists, or whether something is or is not so. These are some of the a priori tendencies, or frames of thinking.

Aside from a priori forms of synthesis, there are also a priori forms of intuition (Anschauungsform), or forms of sensibility—such as time and space. Neither time nor space exists in the objective world; what exists is our tendency (or restriction) to think of something in terms of time and space. For an a priori synthetic judgment to take place, ‘forms of synthesis’ must be united with ‘forms of intuition’. The latter work in the stage of sensibility; the former, in the stage of understanding. There is yet a higher stage of cognition—that of reason.

The cognition of a flower, for example, comes about as follows. The flower has sensible qualities—such as color, shape, and fragrance. It also contains the ‘flower-in-itself’, which lies forever beyond our perception. The ‘flower-in-itself’, is the essence of the flower, which transmits to us its color, shape, fragrance, etc. Even though the sensible qualities of the flower are perceived by our senses, the flower-in-itself cannot be perceived. According to Kant, then, the flower sends material elements to the senses and stimulates (affizieren) the senses through these elements.

The elements of the flower, thus caught by the senses, are first recognized through having forms of intuition applied to them. The sense-impressions, united with forms of intuition, are then connected with the forms of synthesis; the result becomes the object of cognition.

How are the forms of intuition connected with the forms of synthesis ? According to Kant, there must be a force to make this connection, which is imagination (Einbildungskraft). Imagination, then, unites the two forms, thus enabling us to complete the judgment, “this is a flower.”

Where does imagination come from, or what is its basis? It comes from the transcendental unity of apperception (transzendentale Apperzeption), or consciousness in general (Bewufstsein uberhaupt), or pure self (reines Ich). It is on this basis that imagination enables judgment to occur. Consciousness in general is always flowing as an undercurrent in the judgments and experiences of man. This is the main point of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason.

The features of Kant’s epistemology can be summarized as follows: (1) Forms of intuition and forms of synthesis are applied to sense-impressions received from the thing-in-itself, in order to constitute an object of cognition. Imagination is the force that unites these two thinking forms. The object of cognition is neither subjective nor objective for it is a synthesis of subjectivity and objectivity. (2) the thing-in-itself (Ding an Sich) cannot be cognized. (3) man has a priori forms before his experiences. This is a brief summary of Kant’s epistemology.

Cognition, therefore, can be achieved by applying forms of intuition and forms of synthesis to sense-impressions. If any one of these elements is missing, no cognition can take place. In the case of God, for example, Kant says that we cannot determine whether or not He exists, because God cannot be an object of cognition. As there are no sensible qualities in God, He cannot be seen, heard, or tasted; our mind, therefore, cannot obtain any sense-impressions from God. Without these, no cognition can take place. Even though we may have concepts of God, we cannot have a cognition of Him or of His existence.

In spite of his exclusion of God from the world of scientific cognition—to which he clung doggedly—Kant nonetheless believed in God, and said that man postulates God’s existence. How can we explain this?

The answer has to do with man’s need to lead a good moral life. In order for man to live, he needs, not only cognition, but also practice. In the realm of practice, we are guided by ‘practical reason’, which is different from ‘pure reason’, or the reason needed for acquiring knowledge. Practical reason guides us in making decisions about how to live and how to behave; it presupposes man’s freedom, for our decisions must be made freely. Practical reason and pure reason differ from, and do not interfere with, each other; pure reason cannot control practical reason, neither can practical reason affect pure reason.

In order to know how we should live and behave, we need the highest standard of good, which is God. Thus, we cannot but accept God as a postulate of practical reason. Practical reason directs the will, which in turn directs actions. When the will is directed by practical reason it is called ‘good will’. Man’s behavior should be guided by good will.

The directives of practical reason are called ‘categorical imperatives’, which are unconditional orders. These do not originate from some purpose—such as the purpose to make a profit or to gain popularity. They originate from practical reason and command us to do good unconditionally. Belief in God is what keeps our practical reason in the right direction; thus, God’s existence must be postulated. Furthermore, we need to believe in the spirit-world, for similar reasons. Kant was well informed about the spirit-world by Emanuel Swedenborg; he believed in it at first, but denied it in the end.

2. The Dialectical Method of Marxism

Marx, Engels, and Lenin said that a cognition is the reflection of an outside object on our consciousness. In order to be complete and exact—they maintain—cognitions must be verified through practice. True cognition comes both from receiving what reflects on our consciousness from outside (natural world) and from working to practice it outside (in the natural world).

There are three stages in dialectical cognition: (1) the perceptual state of cognitions—that is, the stage of sense-perceptions and impressions; (2) the rational stage, where conception, judgment, and inference take place; (3) and the practice stage. When compared with Kant’s epistemology, the second stage corresponds to the union of ‘understanding cognition’ and ‘rational cognition’. The three stages of dialectical cognition are explained in detail in Mao Tse-tung’s On Practice. By classifying ‘practice’ as the highest stage, the communist philosophy is in effect saying that the purpose of every cognition is for practice. In other words, one should study or conduct research for the sake of practice, which is understood to be the social revolution, as Mao Tse-tung spells out in On Practice.

Knowledge is increased and expanded through the spiral repetition of cognition, practice, recognition, repractice, and so forth. In the beginning, knowledge contains only relative truths; as the process of cognition goes on, it progresses toward absolute truth (according to Lenin).

Mao Tse-tung did not mention ‘absolute truth’. He only said that knowledge increases through the spiral repetition of cognition and practice of the relative truth. Lenin, however, accepted the possibility of absolute truth, as defined by him. He did not say that knowledge is absolute (or else the progress of science would be stopped); nevertheless, he said that a system of thought can be considered “absolute truth” if it can explain things most reasonably for a given age. Absolute truth for an age, therefore, is the synthesis of the relative truths of that age. These are the main points of the dialectical theory of cognition.

II. Unification Epistemology

A. The Source of Cognition

Does cognition take place in the stage of sensation or in the stage of understanding? In other words, is the source of cognition the sensation that comes from the object, or is it the reason of the subject?

These questions are related to the controversy between empiricism and rationalism. For empiricists, cognitions originate from sensations; the role of the objects (all created beings) is stressed. For rationalists, cognitions originate from the subject’s reason; the role of the subject (man) is stressed.

The Unification Thought view on the origin of cognitions is based on the Unification Principle teaching that every created being is the object of man; in other words, every created being exists for, and must be cognized by man. This implies that all things were created in the expectation of man’s appearance on earth.

This view of the relationship between man and other created beings is actually unprecedented in philosophy. Kant, Hegel, and Marx, for example, took a different position, claiming that man is not the subject, but just a member of creation. They thought that all things existed by accident and for no special reason, before man’s appearance; when man appeared, he utilized those things, since they happened to be available.

Schelling’s theory of identity (identitat philosophie) says that the starting point of man and all creation is God; all beings are phenomenal forms of God. God manifests Himself, first, as nature; next, as man. One may think that this philosophy explains the necessary relationship between man and creation, but in actuality it relegates man to the level of all creation.

In Hegel’s philosophy, man and all beings are phenomenal forms of the Idea (God). Hegel’s theory is, in this respect, the same as Schelling’s theory of identity. Why does the Idea undergo self-development, giving rise to creation and to man? He explained this matter with the dialectic theory of thesis-antithesis-synthesis. In our view, however, the dialectic is not the correct explanation of the reason for the self-development of the Idea; it seems only to justify Hegel’s own theory of the self-development of the Idea. Actually, neither Hegel nor Spinoza nor Schelling were able to clarify why man is necessarily distinguished from the rest of creation.

In the Unification Principle view, man cannot exist without creation, and creation is meaningless without man, since man is the subject over all created beings, which are his objects. Man is not only the subject of cognition but also the subject of dominion. The necessary relationship between subject and object was determined in God, even before man was created.

A characteristic of the subject is to have selectivity and autonomy. Man is not a passive recipient of random sensations; he selects certain elements and excludes others. Unification Epistemology maintains that man’s subjectivity is involved in cognition. Of course, the sensible qualities of the object, also, are necessary for cognition to take place.

In conclusion, the impasse in the controversy between empiricism and rationalism came about because the relationship between subject and object was presumed accidental. According to Unification Thought, both reason and experience are necessary for cognition, and true cognition is based on the unity of these two. This unitive view of the source of cognition is derived from the necessary relationship between subject and object.

B. The Essence of the Object of Cognition

Is either the realistic or the idealistic approach to the object of cognition correct? Here I wish to present the Unification Thought view on the essence of the object of cognition, relating it to those two traditional views.

In “Ontology” I said that man is the integration of all beings in creation, and that all these beings are made in the image of man.

There is a similarity between man and all creation. Although man (Adam) was the last to appear in the phenomenal world he was created first in the world of idea (Logos), as the standard for all creation.

Man is the microcosm, (encapsulation, integration) of the universe. Consequently, all the elements of the universe exist in man as a “prototype,” no matter how small man may be physically.

The concept of prototypes occupies a cardinal position in Unification Epistemology. I will now discuss it briefly and will present a more detailed explanation further on in this chapter. Cognition is a judgment, such as “This is …”; a judgment can be compared with a measurement, which needs a standard. When I measure something, I must know the units of measurement in order to understand the dimensions of the thing being measured. Similarly, we need standards of judgment in cognition. Man does have such standards within himself, for he is the encapsulation of the entire creation. For example, within himself he has the standards of a flower and a tree, which correspond to a flower and a tree outside. These standards exist in man as prototypes, which correspond to the structure, elements, qualities, and so on, of all beings outside him.

Understanding that man has the whole universe (in prototype) within himself is an important key for establishing Unification Epistemology. The prototypes exist in the mind as ideas; created beings, however, exist outside. By bringing these two together, Unification Epistemology turns out to be the unity of idealism and realism.

For Berkeley, ‘to be is to be perceived’ (esse est percipi). Thus he limited his area of concentration to ideas in the mind. The realists, on the other hand, limited their area of concentration to outside material substances. By contrast, Unification Thought says that cognition is accomplished by the union of both. This conclusion, however, has not been reached simply through putting together idealism and realism; it is a logical deduction from the Unification Principle.

C. Necessary Conditions For Cognition

1. Content and Form

Content is usually understood as those qualities in the object that can be perceived through physical senses—such as color, smell, and shape. Form has many interpretations, according to the various philosophers.

Kant’s thinking form is transcendental—that is, existing in man’s mind before his experiences. Content belongs to the object, and form belongs to the subject. In Marxism, the form in man’s mind is a secondary form; it appears when an existing form in the objective world is reflected on man’s brain.

In Unification Thought, the object perceived has both content and form. A flower, for instance, has content (shape, color, fragrance, etc.) and form (Sung Sang and Hyung Sang, positivity and negativity, etc.). Not only the object perceived, but also the subject (man) have both content and form. Since man has all the elements of every being within himself, he necessarily has content and form, corresponding to the content and form of all beings. Give-and-take action (collation) takes place between the content and form of the subject and the content and form of the object. The judgment that results from collation is cognition.

2. Autonomy of the Principle and Protoconsciousness

So far, we have explained that the subject has content and form, which corresponds to the content and form of the object. This does not refer only to the material aspect. For example, when we say, in seeing a flower, that the red pigment on the retina of our eyes corresponds to the red color of that flower, it does not solve all the problems of cognition, for cognition cannot be realized only through material similarity. Man’s cognition is a mental judgment; thus, the mental aspect of the process of cognizing must be considered.

The material element of an object does not enter the subject (man) as it is. It stimulates the nerve, causing an impulse that forms an idea in the brain. This idea is then collated with the inner idea (prototype), in order to form a cognition.

Unification Epistemology, therefore, asserts that we are able to recognize the content and form of objects only because we already possess a corresponding content and form in our consciousness. In order to recognize a flower in the objective world, for example, we need a previous image of a flower within us. Without the content and form in our consciousness (i.e., prototype), we would be totally unable to recognize anything. Thus, we need a clear understanding of how prototypes are formed.

Plato solved this problem through the “doctrine of recollection.” He said that cognition cannot be achieved by the reflection of the object on the mind of the subject. Man’s soul knows everything intrinsically, since it once belonged to the world of Ideas, where it knew all Ideas; upon becoming incarnate in the body, however, the soul forgot those Ideas. When a man sees an object—a flower, for example—he remembers the Idea of a flower, which he once knew, and recognizes it as such. Thus, cognition takes place through the process of recollection.

The doctrine of recollection, however, can hardly explain how man gains new knowledge. If all we can do is to remember what we have forgotten, how can we explain the knowledge we gain through actual experiences and studies throughout our life? Unification Epistemology, on the other hand, accounts for the value of real experience.

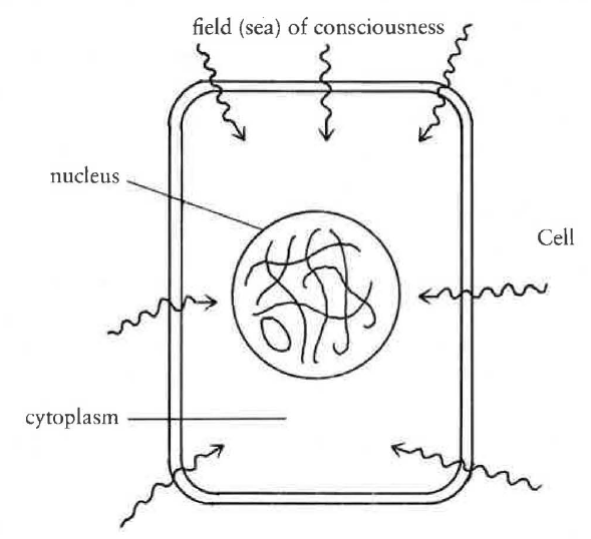

At this point, I would like to discuss “protoconsciousness,” which is the foundation for the development of prototypes. The formation of prototypes in man’s consciousness is connected with the very “life” of the cells in the human body. The life of a cell, as explained in “Ontology,” is the autonomy of the principle; it has perceptiveness and purpose, as well as energy. What is the origin of the life of the cell?1 The life of the cell—the Sung Sang aspect of the cell—is the cosmic consciousness which has entered it. We can conceive of the universe as a sea (or a field) of consciousness, with cells floating in it, permeated by consciousness. When consciousness enters the cell, it conforms to its structure, in a process similar to what happens when water permeates an object: water will enter porous areas, but not dense areas, assuming a certain shape. Likewise, when consciousness enters the cell, it conforms to the shape of the structure of the cell, resulting in the particular consciousness of the cell. We call this particular consciousness “protoconsciousness,” which can be defined as the autonomy of the principle (perceptiveness and purpose) received by the cell from the cosmic consciousness of the universe. (Fig. 15)

Every cell in the body has protoconsciousness, which can be compared with the consciousness of a newborn baby just prior to any experiences with the outside world: it is intrinsic. Since it does not derive from experiences, we call it protoconsciousness, or original consciousness, or causal consciousness.

When consciousness permeates a cell, becoming its life, it also comes to know the contents and structure of that cell. Protoconsciousness has the capacity to know the structure of the cell because it has perceptiveness, just as a film has photosensitivity. This perceptiveness can be described as a transparent homogeneous screen of consciousness (or a film of consciousness), where the image of the structure of the cell is projected. Thus projected, the image of the cell is called “protoimage,” which is the foundation for the development of prototypes.

3. Form and Category

In the human body, cells perform give-and-take action with neighboring cells as well as with distant cells. These mutual interactions are reflected in the film of protoconsciousness; the reflected image is called “image of form” (or image of relation).

The image of form comes from the existing form of the cell. What are the existing forms in Unification Thought? Existing forms can be understood as the conditions of existence that every created being must have as an individual truth body. From among the various existing forms, I will list the ten most fundamental ones, which are derived from the theories of give-and-take action, C-B-H action, and quadruple base, in Unification Thought.

(a) Self-existence and Force: Every being needs force in order to maintain its identity, or self-existence.

(b) Sung Sang and Hyung Sang: Every being has the dual characteristics of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang.

(c) Positivity and Negativity: Every being has active and passive (dynamic and static) characteristics, both within itself and in relation to other existing beings.

(d) Subjectivity and Objectivity: Every being exists either as a subject or as an object: nothing exists in a state of stability without taking either of these positions.

(e) Position and Settlement: Every being needs a certain position in order to exist, and it exists by keeping that position. For example, when a part of our body is lacerated or damaged, cells immediately multiply to fill what has been taken away, or to compensate for what has been damaged. They assume specific positions; no holes or gashes are left. Everything has the nature of settling in a definite position.

(f) Relation and Affinity: All beings have the potential to relate with any other being and do, in fact, relate with a few specific beings. A man, for example, has the potential to marry any woman, and vice-versa; eventually, he may marry one woman. Thus, from a wide range of possibilities, one particular relationship is developed. This relationship is called affinity.

(g) Action and Multiplication: Every being has the tendency to influence others as well as to change themselves and to develop.

(h) Time and Space: Every being exists in time and space.

(i) Original Law and Mathematical Principle: Every being, having been created by the Logos, has laws, which necessarily have a mathematical character.

(j) Infinity and Finiteness: On one hand, beings are concrete existences, and thus, finite; on the other hand, they contain a certain element of infinity. Man’s mind, for instance, is connected with the infinity of God’s Sung Sang; man’s body, to the infinity of God’s Hyung Sang. Inorganic matter performs circular motion, which is eternal; through multiplication, living beings maintain their eternity. These are the fundamental existing forms in Unification Thought.

Since our body is an existing being, it also contains these existing forms. In other words, our stomach, heart, lungs, tissues, cells, and so on, contain existing forms, because every part of the body—organs, tissues, cells, etc—is connected with every other part. The image of the existing forms in the protoconsciousness is called “image of form,” as mentioned before. If man did not have images of form in the protoconsciousness of each cell of his body, he would be unable to recognize such forms in the outer world.

This explanation may seem implausible; yet modern medical science increasingly tends to accept that life (consciousness) in the body is aware of every single part and every single form of the body.

When we observe an object, the information (stimulation given to the receptor) of the content and form of that object is transmitted to the cerebral cortex, where it becomes an image. At the same time, an inner image, or prototype, corresponding to the outer image, is submitted to the consciousness, enabling the process of collation (cognition) to take place. Prototypes are submitted by the “subconscious,” which can be described as a processing center for the information coming from the protoconsciousness of each cell. Subconsciousness, then, is the integration of the protoconsciousness of all cells. (The various steps in the process of cognizing will be further explained in this chapter.)

What about artificial beings, such as spaceships? How can they be cognized? Artificial beings are produced by imitating and synthesizing beings created by God. Man can produce artificial beings because of his inventiveness, which usually works through synthesizing ideas. When our senses receive some uncatalogued information, our consciousness will try to understand it through a process of synthesizing inner ideas, or prototypes, thus forming complex ideas. Brain physiology explains how the synthesis of ideas in our mind is possible: nerve fibers, which make billions of interconnections among brain cells, enable ideas to be synthesized unlimitedly.

Here I would like to present additional information about existing forms and categories. I have explained that all things (including our bodies) have existing forms, and that our protoconsciousness knows them. In their mutual relationships, cells are either controlling (dominating) or obeying (dominated); in other words, they are either subjective or objective. Consequently, the latent consciousness of the cell knows the form of Subject and Object.

Stomach functions are suppressed by the sympathetic nerves of the autonomic nervous system and stimulated by the parasympathetic nerves. Suppression is a negative action; stimulation, a positive action. Through this, the latent consciousness of the body knows the form of Positivity and Negativity.

As mentioned before, the subconsciousness is the integration of the information coming from all the cells. It can be compared with a military headquarters. The headquarters of an Army Division knows all the activities of its batallions, companies, and platoons because it receives constant information from them. Likewise, the subconscious, which receives constant information from organs, tissues, and cells, knows everything about their conditions and forms. This information is not usually sent up to the cerebrum, but is kept in the lower central nervous system. (See Section III of this chapter.) For instance, if the sympathetic nerves are acting so strongly as to impair the activities of the stomach, the autonomic center orders them to let up on their work; this shows that the autonomic nerves, which operate automatically, have a kind of latent consciousness, which knows all the existing forms and conditions of the stomach, in the above example.

The subconscious, therefore, knows the existing forms of all things. When cognition takes place, judgment is influenced by the existing forms in the subconscious, so that our thinking acquires a certain tendency, or restriction. This ‘thinking tendency’ in the judgment is called ‘thinking form’.

When we judge something, for example, we tend to think that there must be an essence behind it. This is a thinking form. (Husserl said we grasp this essence with our intuition.) How do we acquire this tendency? Our subconscious knows the form of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang, and this affects our thinking. When we see the Hyung Sang aspect of a thing, we naturally look for its Sung Sang aspect, because we know that the two are always together. In other words, we have a thinking form of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang. For every existing form there appears a corresponding thinking form. Among the numerous thinking forms, the ten most essential ones, according to Unification Thought, are called “category.” (See “Appendix” on page 357.)

D. Method of Cognition

1. Give-and-take Action between Subject and Object

Cognition operates under the law of give-and-take action. The subject (man) and the object (any being) become engaged in give-and-take action, in the process of cognizing. In order to have an actual cognition, the subject must meet these two requirements: (i) to have prototypes; (ii) to be concerned or interested. Prototypes consist of images of content and images of form within the subject. Images of content are the images of cells, tissues, and organs in the subject’s body; they are formed in the subconscious of the subject through the integration of protoimages. Images of form are the reflected images of the existing forms of cells, tissues, and organs of the subject’s body, in the subconscious. The images of content can be transformed or synthesized in a variety of ways in order to correspond to the content of the object. This is how the prototype of an object is established (the prototype of a flower, for example). The images of form, on the other hand, give rise to ‘thinking forms’, as already explained.

Besides having prototypes, the subject must also be concerned or interested, in order for cognition to take place. This matter will be further discussed in the next item.

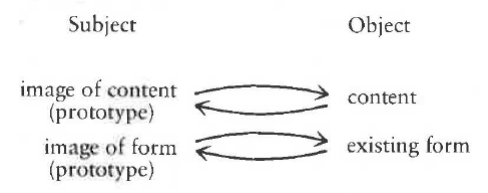

The object must display certain characteristics in order to be cognized by the subject. The object must have content-such as shape, color, and fragrance. Furthermore, it must possess existing forms-such as Sung Sang and Hyung Sang, Positivity and Negativity, and Time and Space. When the requirements of the subject and those of the object are met, cognition can take place, through a process of matching the content and form of the subject (prototype) with the content and form of the object. (Fig. 16)

In the diagram expressed in Fig. 16, ‘object’ refers to the image of content (sensible qualities) and the image of form (existing form) of the object. Sensible qualities-such as shape, color, sound, and fragrance-as well as existing forms-such as Sung Sang and Hyung Sang, and Subjectivity and Objectivity-are perceived by our senses. This information is transformed into ideas (images) in the cerebral cortex. These images correspond to what philosophers have traditionally called “sense-impressions.” The subject compares this image with the prototype existing in himself. This is called collation. When the prototype matches the image, cognition occurs.

Let us ask now how a prototype is formed in the subject. A newborn baby cannot recognize a flower clearly. The image of the flower is vague because the prototypes in his subconscious lack clarity and definition, as his nerves and brain cells have not fully developed yet. As he grows, his prototypes become clearer and more sharply defined; thus, he can recognize flowers more easily.

Nevertheless, he would still have to ask someone about aspects that he could not recognize. He would be taught that a particular flower is a rose, for example. Then the image of a rose would be inscribed in his memory. When he sees a rose again, he will recognize it at once, because the image of a rose, which has been stored in his memory, will spring to his mind immediately; by comparing the outer image with the information stored in his memory, he can recognize as a rose the flower he sees. Thus, we cannot say that prototypes exist a priori, for they are not fully established in a newborn baby; neither can we say that subconsciousness is entirely intrinsic, for it operates through nerves and cells.

When we see a flower, the prototype of a flower comes to mind immediately, but we do not necessarily know what kind of flower it is. Once the flower has been identified—as a rose, for example—its image is inscribed in our memory. This information is not conceptual, but actual; it will be stored in certain brain cells. We may forget this image after a while, but it will not disappear; the information can be retrieved whenever needed.

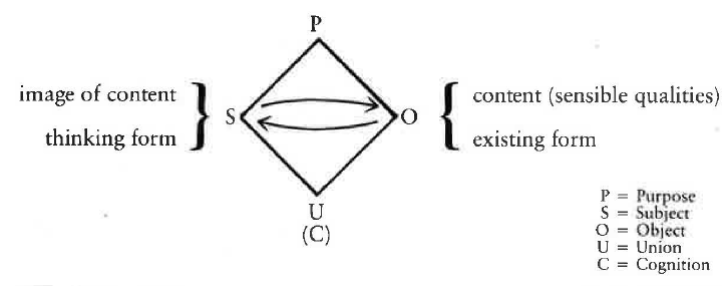

Since cognition in Unification Thought occurs through give-and-take action, to cognize is to form a Quadruple Base. Cognition is the result (United Body) of the give-and-take action of collating the content and form of the subject (prototype) with the content and form of the object, centering on purpose.2 This is the “theory of collation,” in contrast with Kant’s “theory of synthesis” and with Marx’s “theory of reflection.” (Fig. 17)

2. Activeness of the Subject in the Process and Development of Cognition

As the subject, man controls the process of cognition. He may simply ignore the information coming through his senses, or he may select specific kinds of information as objects of his cognition. Someone walking along a crowded street, for example, may choose to disregard sights and sounds and to concentrate on his own thoughts. One of his friends may say later, “You snob! Why didn’t you answer when I said hello yesterday?” He may have seen his friend or even heard his voice, but no cognition took place because he wanted to concentrate on his thoughts.

Another example is a family working at a lighthouse. In the beginning they are disturbed by the sound of the waves and can hardly sleep at night. But after a while, they become accustomed to the noise and are no longer disturbed by it. If the baby in that family cries at night, however, the mother will wake up immediately, even though the sound level of the baby’s voice is only a fraction of that of the waves. The mother is awakened, not so much by the sound itself, but by her concern for the well-being of her child.

Give-and-take action is centered on purpose; the more explicit our purpose, the more exact the resulting cognition. If we look at someone in order to find good points, for example, we will find them; if it is bad points that we are looking for, we will find them, too. A flower is much more beautiful if we look at it in order to see beauty. This reminds us of Jesus’ saying, “Heaven is in the midst of you.” Most people are not conscious of the purpose for which they are thinking, although some purpose—be it good or bad—is always there.

If someone wants to know something more thoroughly, the best way to do it is through practice. Thus, I do not disagree with the Marxist view that cognition deepens through the three stages of perception, reason, and practice, and that cognition develops in a spiral form (endless cycles). Mao Tse-tung says in On Practice,

Start from perceptual knowledge and actively develop it into rational knowledge, then start from rational knowledge and actively guide revolutionary practice to change both the subjective and objective world. Practice, knowledge, again practice, and again knowledge . This form repeats itself in endless cycles, and with each cycle the content of practice and knowledge rises to a higher level.3

When the subject is concerned or interested (though unconsciously), give-and-take action leading to cognition can be initiated. The more this process of cognizing is repracticed, the more exact the resulting knowledge will be. The process of repractice develops new cognition because of the resulting association and synthesis of ideas.

In Unification Thought, also, there are three stages of cognition: the formation stage, the growth stage, and the completion stage. The formation stage is the perceptual stage, in which the sensible qualities of the object are received in the brain through the senses, producing an image in the mind. The mind calls up a corresponding prototype. The growth stage is the stage of cognition, through collation between the outer image and the prototype; through their give-and-take action, a quadruple base is formed. ‘Thinking forms’ are applied and the information is cognized, producing understanding. This is the stage of understanding, in which cognition is completed in one level. In the completion stage one thinks freely without seeing the object. In the case of a flower, for instance, one may consider when it was planted, why it was planted, and so forth. It is said that fourteen billion brain cells are connected with one anocb r in the brain—not in a conceptual way but in reality—as in a network of telephone wires. Information fr rn outside eem to come chiefly to the parieto-temporo-preoccipital association area through the various sensory areas. It may be there that the information is recognized. If it cannot be recognized, all the nerve cells in the brain seem to be ordered to send more information (prototypes) about the object. A final synthesis of information may be carried out in the frontal association area, as explained below.

3. Priority and Development of Prototypes

I would like to return to the subject of prototypes once again. When a clock was first brought to Korea in 1631, people did not know what it was. They thought it was a bell, since it rang at different times; they called it a “self-ringing bell.” They had no prototype for a clock, so they applied what they had: the prototype of a bell. After much puz:iing, they finally came to know that it was not a bell, but a device to tell time. Thus they acquired the prototype of a clock, and their knowledge increased. Through experiences, therefore, we gain new ideas and enrich our prototypes, mainly through the association and synthesis of old ideas.

Kant says that man has a priori forms (understanding forms); Plato maintains that man’s soul knew all ideas prior to entering the human body. Unification Thought, however, says that the prototype is formed on the basis of the physical body of man. Before the ovum is fertilized by the sperm cell there are no prototypes. When a baby is born he already has prototypes, even though he has had no experiences with the outside world. He can have prototypes because he has a physical body. Subsequent experiences will add to the newborn baby’s germ-like prototypes, forming a standard for later experiences. In con lusion, prototypes comprise two types of contents: (i) “a priori ideas,” or intrinsic ideas, which originate from the individual’s intrinsic experience of his own physical body (cells, tissues, organs, and so forth); (ii) “pre-experienced ideas,” which derive from actual experiences with the outside world through a learning process. This aspect of Unification Epistemology is referred to as “Priority of Prototypes,” which contrasts sharply with Kant’s “a priori forms.” Man’s prototypes, obscure during his childhood, develop as he grows (both in the aspect of “a priori ideas,” through the growth of his nervous system and cells, and in the aspect of “pre-experienced ideas,” through the expansion of his experiences) until they finally become complete.

III. Cognition and Physiology in Unification Epistemology

Developing the basic framework of Unification Epistemology has been quite an adventure, so to speak. I have attempted to deduce its canons solely from the premises of the Unification Principle. At first I encountered a great deal of difficulty in organizing it, but I just had to persevere. Epistemology is so crucial to any philosophical system that without it the whole system of Unification Thought might be in jeopardy.

There were no research materials to which I could refer. No one, except Reverend Sun Myung Moon, has ever told me that a cell or an organ has life (consciousness) within it. The Unification Principle asserts that every existing being is a united body of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang; the cell and the organ are no exception. It also maintains that man’s spiritual senses are matured on the basis of the physical body. I have rooted Unification Epistemology on these foundations. Moreover in the development of this theory, Rev. Moon has at times guided me even when dealing with puziing specific issues.

My desire, of course, was to find a scientific foundation as well. It often happens that deductive explanations proposing a general truth initially lack scientific verification. In my case, also, when I assumed deductively that cells have protoconsciousness as their Sung Sang, I had no scientific evidence to substantiate it. On the other hand, if a theory is demonstrably logical, consistent, and free of contradictions, it can be considered true, even though it has not yet been scientifically validated. Based on the Unification Principle and on Rev. Sun Myung Moon’s words, I was able to establish Unification Epistemology as a theory, under such conditions. After completing my exposition, I found that cybernetics supports our theory scientifically; I was reassured that Unification Epistemology is indeed correct.

Let us now discuss one of the vital epistemological points: the relationship between cognition and man’s physiology.

A. Mind and Brain

According to the Unification Principle, Sung Sang and Hyung Sang are as inseparable as two sides of a coin. The three tage of cognition—perception, understanding, and reasoning—have been explained by Kant and others a purely mental phenomena. In the Unification Thought view, however, mental processes are necessarily accompanied by physiological process (especially cerebral processes). Accordingly, cognition is not a purely mental phenomenon, but is a complex phenomenon of both mental and material (cerebral, nervous) processes. In order to clarify the Unification Thought view, I will briefly and schematically discuss the physiological function of the cerebral cortex, based on recent cerebral physiological discoveries.

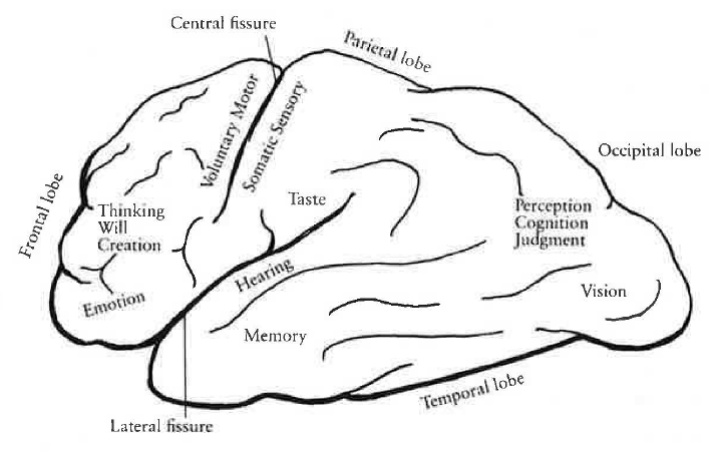

The surface of the cerebral hemisphere is divided into four lobes: frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital. There are many furrows on the surface of the cerebral hemisphere, and the sections separated by furrows are called gyri. The main furrows are the central fissure (fissure of Roland), which separates the frontal lobe from the parietal lobe, and the lateral fissure (fissure of Sylvius), which separates the temporal lobe from the frontal and parietal lobes.

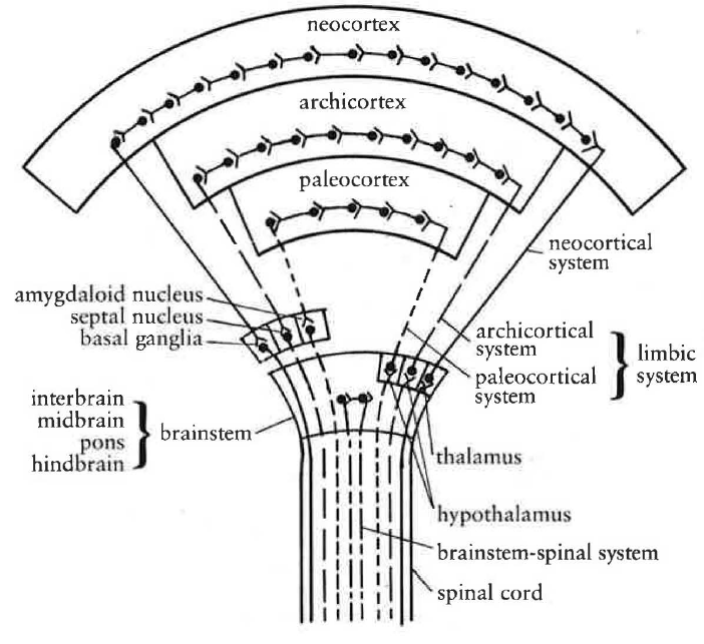

Embryologically, the cerebral cortex consists of paleocortex, archiocortex, and neocortex. The paleocortex and the archiocortex together form the limbic cortex; the limbic cortex and the subcortical structures (including the hypothalamus) together form the limbic system, which is embryologically older than the neocortex. In the case of fish, their cerebral cortex consists primarily of paleocortex; in the case of amphibia, it consists primarily of paleocortex and archiocortex. The neocortex begins to appear in reptiles and develops most remarkably in man; it is closely related with the limbic system through the hypothalamus and me ocortex.

The neocortex of man covers almost the whole surface of the cerebral hemisphere. It comprises three parts: the motor area, the sensory areas, and association areas. The motor area located in front of the central fissure, controls voluntary movements. The sensory areas are responsible for sensations from stimulation received through the sense organs. The sensory area con ist of the somatic sensory area, visual area, auditory area, and so on. The somatic sensory area which lies just behind the central fissure, is responsible for the sen ations of the skin. The visual area, in the occipital lobe, is responsible for the information from optic nerves; and the auditory area, in the temporal lobe, is responsible for the information from auditory nerves. Other sensory areas include the gustatory area and the olfactory area.

The remaining areas, known as association areas, are related to the higher integration faculties, such as cognition, judgment, memory, will, and integration of motions. I would like to discuss the faculties of the association areas in greater detail, since a clear understanding of them will clarify Unification Epistemology.

The association areas consist of three parts: (i) The frontal association area, which is located in the frontal lobe and is involved in the functions of reasoning, emotional control, will, creativity, and integration of movements; (ii) The anterior temporal association area, which lies in the frontal part of the temporal lobe and is responsible for memory; (iii) The parieto-temporo-preoccipital (PTP) association area, which extends from the parietal lobe to the temporal and the occipital lobes and is the locus of perception, cognition, and judgment. (Fig. 18)

Since the PTP association area is closely related to cognitive activities, damage in this area will cause failure in some aspect of the process of cognizing, even if the sensory areas themselves are working properly. If it is damaged in its parietal part, tactile agnosia may result, causing the individual to become insensitive to the things he touches, even if his skin sensation is normal. If damage occurs in its temporal part, auditory agnosia may result, causing the individual to become insensitive to sounds, even if his hearing sensation is normal. Furthermore, if the PTP association area is damaged in its occipital part, visual agnosia may result, causing the individual to become unable to distinguish things seen, even if the visual sensation is normal. In addition, since the PTP association area is also involved in the cognition of.time and space, damage to the specific part where this cognition takes place may result in apraxia, making the individual unable to perform voluntary movements, even if no paralysis actually exists.

The part of the brain responsible for memory is the anterior temporal associaton area, which we may call a memory center. Memories themselves are probably not stored here but are retrieved to this area from the lower parts of the brain, especially from the hippocampal area, in the limbic system. The memory center acts as a processing center, sending information to the storage areas (subconscious) and retrieving it when necessary.

Based on the above information we can attempt a description of the pathway of the process of cognizing, which may be described in the following steps.

- The information from the outside world comes through the sensory organs and nerves to the various sensory areas, where it gives rise to visual images, auditory images, and so on.

- Those images are transferred to the PTP association area through nerve fibers, where they are integrated and prepared for the process of collation.

- Prototypes are retrieved from the memory storage areas by the memory center in the anterior temporal association area, and are sent to the PTP area for collation.

-

Collation takes place between the outer image and the inner image (prototype). At this point cognition occurs.

After that, there are two possibilities:

- either the newly acquired information goes to the memory center in the anterior temporal association area and then is transferred to the subconscious in the lower parts of the brain;

- or the newly acquired information goes to the frontal association area in the frontal lobe, to become data for the function of reason, will, emotion, and creativity. (The information sent to the memory center can also be forwarded to the frontal association area any time it is needed.) In the frontal association area all the necessary knowledge acquired through experience can be gathered and integrated in the creation of new plans to be used in practice.

In conclusion, cerebral physiology supports the theory of three-stage cognition of perception, understanding, and reason, for it gives a clearly distinguishable physiological base for each of these theoretical stages. Furthermore, cerebral physiology also supports the theory of the unity of cognition and practice, by showing how newly acquired knowledge can be used to create new plans.

B. Elements of the Inner World and Cybernetics

Now I would like to discuss certain activities of the body, as an effort to present a scientific base for the theory of the existence of consciousness in the cell (protoconsciousness). Cybernetics is the. study of the adjustments and control functions of self-regulating mechanisms. The term can be applied both to living beings and to automatic machines, as both can make appropriate responses to outside stimuli, especially through feedback. For the purpose of this discussion, feedback can be understood as the process whereby a living organism detects a stimulation and uses it to control the process producing the stimulation. (The operation of a thermostat to control room temperature can be given as ai:i example of how feedback works.) Cybernetics can also be described as the control mechanism operating to attain and maintain homeostasis. As applied to our physical body, homeostasis refers to a tendency of organs within our body to maintain their composition and function through a coordinated response to stimuli tending to affect them. Stimuli can come from the environment (physical and social surroundings) as well as from within man himself—from organs (heart, stomach, lungs, liver, etc.), from tissues, and even from cells. Homeostasis keeps the organism stable in its relationships to the numerous stimuli from the environment and from within the body.

If the weather is hot, for example, pores at the root of the hair open, and heat is released through sweat. If it is cold, we begin to shiver in order to keep the body warm. If there is too much light, the iris contracts; if not enough light, it dilates. Pulse rate increases when a person runs and returns to normal soon after he stops running.

If someone has appendicitis, certain nerves send directives to the inflamed part to try to restore it. Soon the muscles in that area tighten in order to protect that area, which is called the MacBarne point, or the oppressive pain point. If the person is pressed in the lower right region of the abdomen, he will feel pain because of the tautness of the muscles. At the same time, white corpuscles are sent in to heal the inflammation. This again, is homeostatic, or reflex activity. Even a cell displays homeostatic functions: the nucleus responds immediately to externally caused cytoplasmic disturbances.

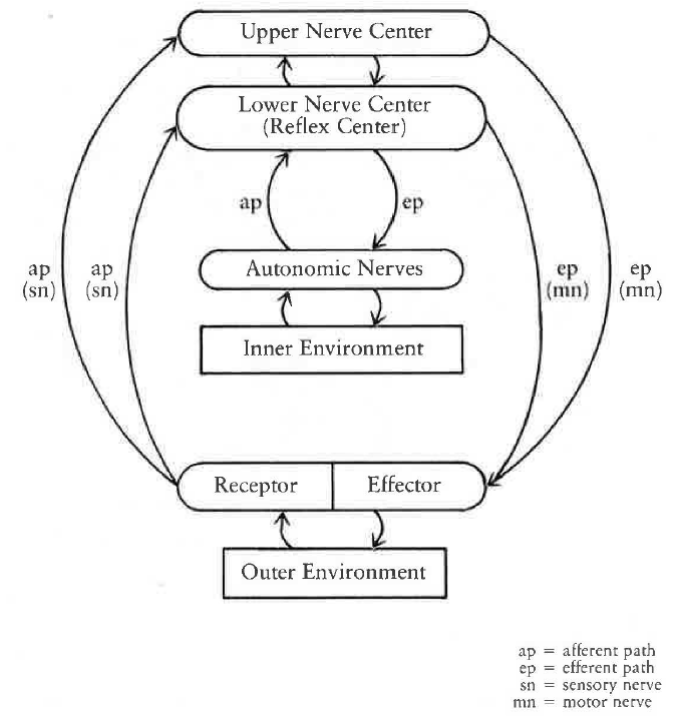

Homeostatic activities are controlled by the lower nerve center of the body, which is also called the reflex center. The lower nerve center (LNC) comprises the limbic system below the neocortex, the interbrain (thalamus and hypothalamus), the midbrain, the hindbrain (cerebellum, pons, medulla), and the spinal cord. The control of the dilation and contraction of the iris, for instance, takes place in the midbrain. When information cannot be handled by the midbrain, it is sent to the hypothalamus. Almost all internal information, however, is dealt with in the part of the brain below the hypothalamus. It is said that it is now certain that the hypothalamus is controlled by the limbic cortex. (Fig. 19)

This is similar to the administrative processes of a nation. In Korea, for example, information that cannot be handled by the Myeon (subcounty) is sent to the Gun (county); if it cannot be handled there, it is sent to the Do (province); if necessary, it can finally be sent to the central government. Almost all information, however, is dealt with below the Do.

The cerebral cortex is what would correspond to the central government of a nation. It is the location of the “awake” consciousness, dealing primarily with stimuli from the outer environment. When the lower nerve center (LNC) cannot deal with internal stimuli, it sends a message to the upper nerve center (UNC), metaphorically saying, “l cannot deal with this stomach ache; please do something.” The UNC judges the information and may reply something like, “This needs to be treated in a hospital at once.” We must recognize in this the existence of selectivity in the LNC. Selectivity implies consciousness.

Stimuli reach the nerve centers through different nerve pathways, according to their origin and nature. Those from the outer environment go to the UNC (cortex) through the sensory nerves; a suitable response is given by the UNC through the motor nerves (moving hands, legs, or whatever). On the other hand, information from within the body reaches the LNC through the afferent autonomic nerves; the LNC, in turn, sends an appropriate response through the efferent autonomic nerves. This is the reflex pathway. Reflex actions are initiated in our subconscious mind; we are largely unaware of their operation. (Fig. 20)

As we can see, there are myriad functions happening simultaneously in order to keep our physical body balanced and well-maintained. Innumerable bits of information are received at the nerve centers, analyzed, and classified; an equally fantastic number of decisions are made, and orders are issued according to those decisions. What, then, is the subject of all these activities? What judges the information received at the nerve center and issues appropriate orders? In other words, what causes the homeostatic functions of the body to take place?

As mentioned above, the LNC usually deals with stimuli from within the body, through reflex action and control. At times, however, the LNC sends certain types of information to the UNC , to be dealt with at the cerebral cortex. This means that the LNC “knows” that there is a problem, takes action to solve the problem, and has the ability to discriminate among the various stimuli, choosing the ones to be forwarded to the UNC. The fact that the LNC can understand and analyze stimuli and can make necessary decisions—including even that of whether or not to send information to the UNC-means that it actually has consciousness. The cybernetic phenomena within a cell—that is, the cell’s ability to cope with something wrong inside it or to make appropriate responses to outside stimuli—imply that even a cell has consciousness, or more precisely, protoconsciousness. This conclusion is not only derived from the Unification Principle view—which says that every existing being has both Sung Sang and Hyung Sang aspects—but is also affirmed by physiological science.

This conclusion is also supported by the fact that actions that are normally performed through the reflex control of the LNC can at times be performed through the intentional control of the UNC. Yogis, for example, who have spent a lifetime disciplining themselves, have shown that certain physiological processes can be controlled at will—such as pulse rate and the temperature of different parts of the body. In the case of the iris, it should contract when too much light is coming in and dilate when there is not enough light, as mentioned above. This is a reflex process. There are those, however, who can cause the reverse procedure through intentional control.

Another example, which you may have heard, refers to people who have asked to be buried alive, only to emerge as large as life when unearthed weeks later. There is a scientific explanation for this. In the heart, blood is pumped from the atria to the ventricles, and from there into the arteries. There is a valve between the atrium and the ventricle, which opens and closes like a door. By ordering the valve of the heart and the heart muscles to slow down, these people can induce a state of hibernation and stay buried for weeks. Such experiments have been carefully observed by skeptical scientists. Another example is the baffling case of islanders in the South Pacific who practice walking on scorching hot stones in bare feet, without incurring the slightest burn.

In these instances of intentional control, we cannot but recognize that the upper nerve center is controlling the lower nerve center.

This shows that the consciousness of the LNC is of the same quality as that of the UNC, except that the former is hidden (subconscious), whereas the latter is apparent. In other words, there is no essential difference between intentional control and reflex control, since in both cases consciousness is the subject. This is a key point for verifying the existence of protoconsciousness.

Accordingly, there are various levels of consciousness, or life, in man. The higher the position in the brain, the more precise and dear the consciousness becomes. As explained before, life is a manifestation of God’s Sung Sang. It can manifest itself in various levels—such as the level of a single cell or the level of man’s cerebral cortex, which manifests God’s Sung Sang to the highest degree.

That a cell can respond to stimuli points to consciousness within it. Though on a small scale, the cell does carry out cybernetic activities. The consciousness (life) of the lower nerve center is of a slightly higher dimension than that of individual cells, tissues, and organs; the LNC, in fact, stores, judges, and integrates information from the cells, tissues, and organs. This means that the prototypes that reflect the inner environment—that is, the prototypes before one’s experiences with the outside world—seem to be stored in the LNC, especially in the limbic system.

The limbic system is said to be directly related to instincts and animal-like emotions. Information from the cerebral cortex may also be stored here. Emotion and instinct are closely related to memory. Although a memory center appears to exist in the temporal lobe—as discussed above—information from experiences is said to be stored in the area centering in and around the archicortex (hippocampal formation). Accordingly, this area has the functions of recording, retaining, and recalling information.

The upper memory storage center of the archicortex is connected with many lower centers-such as the hypothalamus, mid-brain, hindbrain, and spinal cord. All of them can be said to form the memory system. The various bits of information are stored as prototypes in their appropriate positions. Prototypes acquired from the external environment as well as those acquired through reflex processes are stored in this way. As explained before, these prototypes can be recalled to the consciousness of the cerebral cortex to be collated with outer information, as part of the process of developing new cognitions.

C. Transmission of Information

Why don’t messages stop when they come to the tip of a neuron (nerve fiber)? The sending tip (telodendria) of a sensory neuron leads to the receiving tip (dendrite) of a neuron in the central nervous system. There is, however, a gap (synapse) between them, which is filled with a fluid; the information has to be transmitted across this gap. The fluid is not only in the synaptic gap, but surrounds the nerve fiber.

The transmission of information through the axon (long, cord-like part) of a nerve fiber is an electrical process. The nerve fiber is enveloped by a membrane which in its resting state is polarized: the outside has a positive charge, while the inside has a negative charge. When the information is passing through the fiber, the polarization vanishes (depolarization). The area of depolarization (the impulse) moves along the fiber. While the impulse is passing, the outside of the membrane is negatively charged, but it reverts to its positive state after the impulse passes.

This negative wave reaches the tip of the fiber, and the impulse (information) is transmitted across the gap filled with fluid, which includes chemical substances, such as potassium, sodium, chlorine, phosphate, and special enzymes. With the aid of enzymes, conveyers (acetylcholine, adrenaline, etc.) are formed at the tip of the nerve fiber. These chemical substances move across the fluid and stimulate the tip (dendrite) of the next fiber, in which the same negative wave appears. The transmission process across the gap (synapse) is purely chemical.

The process of depolarization, though not yet fully understood, is, however, known to be related to the movement of potassium and sodium ions in and out (penetration or permeation) of the membrane. The membrane appears to have selectivity with regard to the permeation of ions; enzymes seem to be connected with this activity. The discrimination of impulses occurs to a certain degree at the

connecting point of the peripheral nerves with the central nerves; a decision is made whether they should be sent directly to effectors in a reflex arc, or should be carried to the brain. This means that conscious action (selection by the consciousness) is at the root of the physiochemical process, controlling both the electrical processes in the fiber (axon) and the chemical processes across the synapse. This understanding is based on the Unification Principle, which says that every Hyung Sang process is necessarily accompanied by a Sung Sang process.

This completes my explanation of the existence of the protoconsciousness of the cell, with its protoimages and images of form, as well as its connection with the consciousness of the cerebral cortex.

D. Spiritual Cognition

The Unification Principle says that the spirit-man receives vitality elements from the physical body and gives living spirit-elements to the physical body. I think that both are spiritual elements and are like refined electricity; among the various physical processes in our body, electrical processes are the most refined. Based on the statement that the spiritual senses develop on the basis of the physical body, we can quite easily link an underlying spiritual function with the electrical flow in the nerve fibers. It may be helpful to think that the spirit-man has nerve fibers that work in correspondence with, and in a similar fashion as, the nerve fibers of the physical body.6

In some cases, spirit-men other than one’s own may help in one’s cognition. Spiritual influence can be exerted in all three stages of cognition—i.e., in the perceptual stage, the understanding stage, and the rational stage. Cognition with spiritual accompaniment is finer and faster than ordinary cognition.

IV. Critique of the Epistemologies of Kant and Marx

A. Critique of Kant

The first problem in Kant’s epistemology is related to his explanation of ‘a priori forms’, which is partially right and partially wrong, from the Unification Thought viewpoint. He considers the subjective thinking form (category), but fails to include the objective existing form. Kant said that time and space are a thinking form; in actuality, they are also an existing form. Two successive phenomena are not just cognized with the thinking forms of time and space; they are indeed caused within actual time and space in the objective world. With regard to plurality (Vielheit), it is not that we just happen to see things in great numbers; a great number of things actually do exist.

The second problem is related with the thing-in-itself (Ding-an-sich). Kant says that the thing-in-itself can in no way be cognized. In the Unification Thought view, however, thing-in-itself corresponds to Sung Sang; we can understand the Sung Sang of something by observing its Hyung Sang, since the two are inseparable, and the Hyung Sang resembles and expresses the Sung Sang.

The third problem is that of imagination (Einbildungskraft), which is said to unite the forms of intuition and the forms of synthesis, either consciously or unconsciously. According to Unification Epistemology, cognition is reached by the give-and-take action between the prototype (image) of the subject and the image of the object. In other words, in the mind, give-and-take action appears between the prototype and the image of the object. This means that we collate the two images to see if they coincide. The mind, or consciousness, does the collating; consciousness, therefore, is necessary in cognition. Kant’s position that unity between intuition forms and understanding forms occur without consciousness cannot, therefore, be considered correct.