9 Theory of Art

Art is a treasured element of mankind’s cultural heritage. In this chapter, we will clarify our attitude toward it. As you probably know, communists value their theory of art highly, because for them art is an efficient means for achieving revolution. Lenin said that all aspects of art—including literature—must be coherent with, and subject to, the policies of the Communist Party. Stalin said that artists are the engineers to reform and reconstruct men’s minds. The communist theory of art is called Socialist Realism, whose aim is to ensure that the content of art and the method of creating it meet with Party policies. When we look at the history of revolutions, we can see how important a role artistic activities have played in them. When I was young, there was a great deal of artistic activity conducted by the communists. They would often put on plays in a house they rented in the countryside. They had two favorite themes: one was about the Japanese occupation of Korea; the other, about the way landowners and capitalists harshly treated peasants and laborers. The effect was the same as openly publicizing their theories. Even now they still make use of different cultural groups—seemingly without any ideological purpose—under the pretext of improving cultural exchange. (These cultural groups are readily accepted in the free world, which stresses the freedom of artistic expression and has no standard or theory with which to distinguish true from manipulative art.) I cannot deny my fear that the engineers referred to by Stalin might indeed reform men’s minds. Clearly, we need a theory of art to oppose such manipulation.

Reverend Sun Myung Moon has begun artistic activities with the “Little Angels” group in order to inspire people to give joy to God. It is not good for art to be used for political contrivance; true art can never be made into a tool of politics, for true art is that which pleases God and man. Another reason why a theory of art is necessary is that when society is restored to its original state, it will be an artistic society, where the Purpose of Creation is completely realized. In that society, people will love one another; for that reason, they will want to dance, sing, and engage in various kinds of artistic activities. In the ideal society, economic problems will be solved; as a result, artistic activities will come to the fore. To those leaders who are trying to build such a society a theory of art is indispensible.

If it is our aim to construct a new culture, we must pay attention to art, for art is the essence of culture. First, we must protect the cultural heritage we already have. This heritage includes architecture, sculpture, music, painting, industrial design, and so on. Communism aims at destroying our cultural heritage. Of course, they act as if they were trying to protect art; yet they appreciate art, not for its own sake, but merely as something to be used for the purpose of publicity. They see no significance in a piece of art that has no propaganda-value. Those who are not well-informed have the impression that communism is protecting our traditional cultural heritage, but this is a fanciful notion.

When we consider such things, we feel responsible not only to inherit our own culture, but to keep it alive, and on this foundation, to develop a new culture. This new culture will come about through the integration of the best elements within the cultures of various nations and racial groups. So, keeping our national cultural heritage is a sine qua non for building a new culture.

I have developed the Unification theory of art deductively from the teachings and Unification Principle of Rev. Sun Myung Moon, making almost no reference to the traditional theories of art. Rev. Moon himself has a highly developed artistic sense, which I would like to make known through this theory. Based on this new theory, we must play a central role in constructing a new culture.

I. What Is Art?

Generally speaking, intellect is related to philosophy; will, to morality and ethics; and emotion, to art. So, art is the emotional activity of creating and appreciating beauty. The purpose of art is to produce joy. In other words, the purpose of creating and appreciating beauty is for people to be joyful. Therefore, in Unification Thought view, art is “the activity of creating joy through the creation and appreciation of beauty.” As explained below, appreciation is a form of creation; accordingly, we can simply say that art is “the activity of creating joy through creating beauty.”

Other scholars define it in various ways. Sir Herbert Read, for instance, said that “art is an attempt to create pleasing forms,”1 which is a view similar to that of Unification Thought.

II. Joy and Resemblance In Art

What is joy? I would like to discuss this point philosophically. The Principle of Creation contains many philosophical points that most people fail to notice when they first read it. The concept of joy comes from the Principle of Creation, and this is an important element in establishing our theory of art. The section in the Principle of Creation entitled “Object of Goodness for the Joy of God,” is related to the creation of works of art. The Principle of Creation says:

Joy comes when we have an object, whether invisible or visible, in which our own character and form are reflected and developed, thus enabling us to feel our own character and form through the stimulation derived from the object.

For example, man feels joy as a creator only when he has an object; that is, when he sees the product of his work, whether it be a painting or a sculpture, in which his plan is substantiated. In this way, he is able to feel his own character and form objectively through the stimulation derived from the product of his work.2

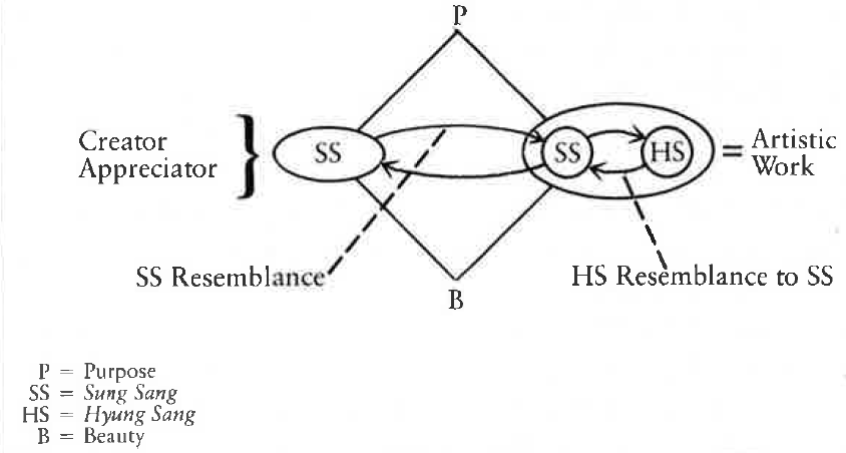

A plan—which belongs to the invisible Sung Sang—is substantiated (objectified) to form a work of art. Works of art, therefore, are objectified plans. The artist’s joy comes when he feels his Sung Sang and Hyung Sang as objectified forms, or as reflected objects standing in a position relative to him, through the stimulation from the object (work of art). In other words, when the subject and object resemble each other, the object stimulates the emotion of the subject; at that moment, beauty is appreciated and the experience of joy comes about.

Odebrecht said that joy is the feeling produced when one’s personality is released from all pressures. What does this mean? Man usually feels that his mind is oppressed by something, sometimes by his own conscience. When he is released from this pressure, he has a feeling of liberation. Odebrecht called this feeling joy. I think there is some truth in Odebrecht’s interpretation.

This reminds me of the effect of alcohol on a drinking person—even though I am aware of the essential difference involved. When someone drinks, the cerebral cortex, especially the frontal lobe, becomes dulled with the effect of the alcohol. As a result, he feels a sense of release, as if the pangs of his conscience had suddenly vanished; he sings and dances happily. What happens in the experience of art is quite different, of course, yet there is a point of similarity: in art, also, one can feel released, through the experience of losing oneself in the fascination of beauty—a kind of catharsis. An example of this would be the experience of joy and release one may feel when watching a fine performance of a play.

A. Resemblance and Prototype

Resemblance is the precondition not only in epistemology and logic, but also in the artistic experience of joy and beauty. When there is resemblance, collation follows and cognition takes place. The same resemblance brings about cognition in some cases, beauty in others. How can this be explained? The concept of resemblance is based on the fact that man is the integration of the whole universe. He is a microcosm, or a contracted body, of the cosmos. Accordingly, the cosmos can be looked upon as the expanded body of man. This is why the subject (man), and the object (other created beings) resemble each other. If the resemblance were limited merely to Hyung Sang aspects, however, the experience of joy would not occur. Some elements of Sung Sang, also, must resemble, corresponding to the resembling Hyung Sang elements. In the subject, this is the so-called “prototype” mentioned in Epistemology. When the object (precisely speaking, the object’s image) and the prototype resemble each other, collation is performed and joy can come about. (See Epistemology, Section 3)

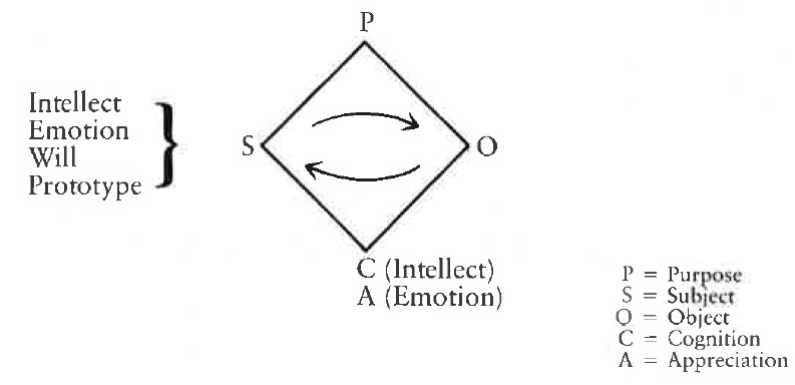

The collation of subject and object elements is accomplished through the give-and-take action between them. In the case of cognition, the give-and-take action is intellectual; in the case of art (when one feels beauty), it is emotional. Actually, intellect, emotion, and will are not independent of one another. It is just that in art, emotion is stronger than the other two. Deciding which of the three functions is more active is sometimes a problem. In appreciation, even though emotion plays the major role, it is always accompanied by intellect. Thus appreciation is accompanied by cognition. (Fig. 28)

B. Sung Sang Resemblance

Sung Sang resemblance means that the Sung Sang of the subject and that of the object resemble each other. The more they resemble each other, the greater the appreciation of beauty.

Let us take Millet’s painting The Angelus as an example. First, Millet must have had a motive (purpose) in painting, for no work of art can be produced without a motive. Millet’s motive might have been his desire to paint his impression of faithful peasants in a farming village. Then, too, the artist needed a theme, or a way to express the motive. In choosing a theme he had to decide, for instance, whether to make the church bell or the married couple the most prominent feature, which may have been difficult to decide. Finally, Millet needed a plan, or concrete details, such as where to put the church, where to place the married couple, and which colors to use. The motive, the theme, and the plan are part of the Sung Sang aspect of a work of art.

When we appreciate works of art, we need also to consider the painter’s way of thinking. To appreciate Millet’s works, for instance, we need to find out more about him as a person by reading his biography or by inquiring about him.

From 1830 (the July Revolution) to 1871 (the Paris Commune) there was a revolutionary atmosphere in France; it is said, however, that due to his aversion to the prevailing atmosphere of violence, Millet moved to a quiet farming village, where he painted farmers who were pure in heart. By learning about Millet’s backgro und , we can understand his mind more fully and feel closer to him; this will lead to a deeper understanding of his painting.

If we are to appreciate Millet’s works even more deeply, we need

to know more about his motive, theme, plan, and way of thinking at the time he created his works. In this way, more Sung Sang relationships of resemblance between us and the work of art will be formed, and greater beauty will become manifest.

C. Hyung Sang Resemblance to the Sung Sang of a Work of Art

The resemblance between the Hyung Sang and the Sung Sang of a work of art is also a necessary factor for the appreciator’s joy. In The Angelus, for example, physical conditions—such as lines, shapes, form, mass (thickness of paint), size, light, and shade are all part of the Hyung Sang aspect. These must be in harmony with one another; besides, they must be a good expression of Millet’s motive, theme, and plan (i.e., the Sung Sang aspect). When the Hyung Sang and the Sung Sang of the work are in harmony, the appreciator can feel beauty in the work. (Fig. 29)

III. What Is Beauty?

A. Definition of Beauty

There have been a number of theories of art, and almost all of them have been concerned with beauty itself. The Unification Principle defines love as “an emotional force that the subject gives to the object,” and beauty as “an emotional force that the object returns to the subject.” Both love and beauty are emotional elements (emotional forces); these two elements, however, are not always equal. In some cases, they are the same; in others, they are not. According to Rev. Moon, in human relationships there can be love both from the subject and from the object, and beauty both from the subject and from the object. The emotional force that the subject gives to the object is always a conscious force. If the object is a person, he or she may love the subject, too; but if it is a “thing,” it cannot do this, because it does not have a conscious emotional force. Whether the object is a person or a thing, it still gives emotional elements to the subject. These elements may be called emotional stimulation. Therefore, we can define beauty as “the emotional stimulation that the object gives to the subject.”

Some people may object to the term “emotional stimulation,” pointing out that, though people have emotions, things do not. Still, it is appropriate to use this term, because emotion is something subjective. Even when the stimulation coming from the object is only physical, the subject can receive it, not just physically, but also emotionally. On the other hand, even if the object is a person who is consciously giving emotion to the subject, still the subject does not necessarily have to receive it emotionally. When he does not, stimulation does not occur. A lot depends, therefore, on the subjective element.

Sir Herbert Read said that beauty is something that gives us a pleasant feeling. Cho Yo Han, a Korean scholar, said that beauty is a quality of the object that satisfies the (subject’s) desire for the spirit of beauty.

Kant, on the other hand, said that to feel beauty is to judge (beurteilen) the subjective purposiveness (subjective Zweckmassigkeit) of an object (Gegenstand) by the emotion (Gefuhl) of pleasantness (Lust) and unpleasantness (Unlust). Kant called this kind of judgment “taste judgment” (Geschmacksurteil). For Kant, therefore, the feeling of beauty can be called the feeling of joy coming from the subjective purposiveness of an object. I will give an example of what he means. Let us imagine a tree coming into flower. What is the purpose of the flower? According to Kant, the flower itself actually has no purpose, but since man has a desire to seek beauty, he looks at it subjectively as if it had the purpose of expressing beauty. In other words, he objectifies his subjective purposiveness in the object, and judges the objectified purposiveness (with an emotion of pleasantness) as beauty. To Kant, therefore, the object of beauty is the object with “purposiveness without purpose” (Zweckmassigkeit ohne Zweck). Kant said that there are two kinds of beauty: grace (Anmut, Grazie) and sublimity (Erhabene). Grace is something that generally gives us pleasure. Sublimity, on the other hand, seems not to give any feeling of pleasure; it does, however, stimulate our sense of beauty, conveying such feelings as wonder (Staunen), solemnity, reverence (Erfurcht), and awe. We sometimes experience the indescribable wonder of nature, or feel deep reverence toward a certain great man. Along the same lines, E. Burke, also, distinguished between the beauty that gives man pleasure and the beauty that inspires wonder, such as the one felt when facing something greater than human dimensions.

More theoretically, beauty can be defined also as “the object’s value felt as emotional stimulation,” for beauty is the object’s value and is, at the same time, an emotional stimulation. The object’s value is not limited to beauty; goodness and trueness, also, are values of an object. Moreover, not only beauty gives man joy; knowing the truth and learning of persons of goodness, also, can bring joy. So, beauty is the object’s value grasped emotionally. If the stimulus coming from the object is grasped volitionally, it becomes goodness; if grasped intellectually, trueness. I will. deal with this point in more detail at the end of this section.

B. The Determination of Beauty

How can we decide on whether or not something is beautiful? The Unification Principle says:

The original value of an individual body is not laten-t in itself as an absolute. It is determined by the reciprocal relationship between the purpose of the individual body (as a particular kind of object centered on God’s ideal of creation) and the desire of man (as the subject) to pursue the original value of the object. Accordingly, in order for an object to realize the original value of its creation, it must unite with man through give and take action, thus forming the original four position foundation by becoming the third object to God.3

This is the fundamental way to determine original value (beauty). Specifically, how is the beauty of anything determined? How, for example, is the beauty of a flower determined? The Unification Principle explains it as follows:

[The original beauty of a flower] is determined when God’s purpose in creating the flower and man’s spontaneous desire to pursue the flower’s beauty are in accord with each other-when man’s God-centered desire to find its beauty is fulfilled by the emotional stimulation he receives from the flower. This brings him perfect joy. In this way, the beauty of the flower will become absolute when the joy which man feels from the flower is perfectly centered upon the purpose of creation.

Man’s desire to pursue the beauty of creation is the desire to feel his own character and form objectively. When God’s purpose of creating the flower and man’s desire to pursue its value are found to be in accord, the subject and object form a state of harmonious oneness.4

The essential points concerning the determination of beauty are found in these passages.

I would like to explain philosophically how beauty may be determined. In general terms, beauty is determined through the give-and-take action between subject and object. Beauty i not something that “exists,” but something that is “felt.” A fact “exists,” but value can only be “felt.” Value is felt by the subject when there is a relationship between the subject and the object. Beauty, therefore, does not exist objectively; it is obtained by the reciprocal give-and-take action between the subject and the object. That does not mean that there is nothing in the object; it must contain something that can give rise to the emotional feeling of beauty. This is actually the essence of value within the object. As explained in “Axiology,” the essence of value consists of (1) purpose of creation (plus theme and plan, in a work of art); (2) the harmony of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang, and that of correlative elements within Hyung Sang (such as the harmony of lines, shapes, color , shades of light, masses, and the harmony expressed in space and time).

What requisites, then, should the subject have in order to be able to appreciate beauty? First, he should have the desire to seek value (beauty) from the work or art; furthermore, he should have a certain standard of way of thinking, view of life, individuality, education, interests, hobbies, ideas, etc., in order to understand and make resemblance with the Sung Sang of the work of art; finally, he should have the harmony of spirit-mind and physical mind and the harmony of the Hyung Sang elements.

In judging actual beauty, the subject’s activeness and concern—which work on the basis of his desire to seek value—are also important. The subject can creatively add his own way of thinking, individuality, ideas, and so on, to the work of art. Accordingly, in the very process of appreciating beauty, an appreciator can, to some extent, create beauty as well. This is called subjective action.

Kant said that the judgment of beauty is a subjective judgment of how much the object is in accordance with the appreciator’s purpose. The feeling of pleasantness, in this judgment, is beauty. Since Kant went little further than to recognize that man requires God, he could not say that all beings were created with a purpose. Accordingly, for Kant, objects such as flowers and birds do not have a purpose to exist. Man, the subject, gives the purpose to them, and the judgment of how much the object lives up to this purpose is the judgment of beauty. Unification Thought agrees with Kant’s view in that beauty is judged subjectively; yet it also recognizes objective purpose, which Kant did not. As all works of art were created according to a certain purpose, so, also, were all created beings. There is harmony in nature because there is purpose. Man’s emotions are stimulated when he perceives this harmony, and a feeling of beauty is generated.

The judgment of beauty is subjective. It is always accompanied by subjective action—that is, the inevitable addition of subjective elements to the judgment of beauty. In judging beauty, the appreciator tries to unite with the work. By creating a resemblance to the work of art, he can appreciate it much more deeply.

Lipps refers to this with the concept of empathy (Einfühlung), which means feeling into or projecting oneself into, the form of the work of art. When someone is crying, we only need to see his tears and look at the expression on his face to realize he is sad. He does not have to say anything. Since we have had the experience of crying when we were sad, we can understand his sorrow by feeling how we would feel if we were in his place.

Empathy corresponds to subjective action in Unification Thought. An actor sometimes pretends to weep, even though he is not at all sad. Special make-up techniques give him the appearance of crying real tears. The audience sympathizes with him and also starts to cry. We can say that the actor has tricked the audience through empathy. An incident that happened in 1945 may be given as an illustration of how empathy works. At that time, F.D. Roosevelt had just died, and a photograph of Stalin, crying, appeared in the newspapers. One journalist said, “Stalin’s eyes are crying, but his mouth is laughing.” I, also, felt that perhaps he was just acting. Though he was probably pleased, yet he could not openly display his satisfaction, because he was afraid of what the American people might think. So, he pretended to cry. He was able to make his eyes look sad, but did not manage as well with his mouth. Stalin, also, may have made use of empathy.

Empathy, here, corresponds to “subjective action” in Unification Thought. Subjective action means that subjectivity is projected upon the object.

C. The Cause of the Feeling of Beauty—Harmony

A work of art contains various elements that can give emotional stimulation to man and can, therefore, be perceived as beauty. What, exactly, is the basis for emotional stimulation in man? It is the perception of harmony in the object. Through perceiving harmony, man can have emotional stimulation and thus obtain the experience of beauty. Accordingly, when the physical elements of a work of art, such as lines, shapes, and colors, are well balanced and harmonized with one another, we can perceive them as beauty and can derive joy and satisfaction from them.

Man can feel this harmony because he himself is originally a harmonious being. Just as the cosmos is a harmonious system, the physical body of man is a harmonious system; in other words, the various elements within his body are in harmony among themselves. Though man has fallen into a sinful state, his mind and body also have a tendency to be in harmony. In this sense, man, originally, is God’s best work of art. Thus, man (the appreciator) can resemble works of art by his own inner harmony. Conversely, if he is not in a harmonious state, he cannot understand the real beauty of a work of art when he sees it. When we appreciate works of art, therefore, we must empty our mind of mundane thoughts and be very calm. When we purify our minds and maintain a harmonious state, we can easily experience beauty from a work of art. This is called contemplation. At the moment of contemplation, the appreciator, who is in a state of harmony, forms a common base with the artistic work, and beauty is experienced.

H. Read said, “The work of art has an imaginary point of reference (analogous to a center of gravity) and around the point the lines, surfaces, and masses are distributed in such a way that they rest in perfect equilibrium. The structural aim of all these modes is harmony, and harmony is the satisfaction of our sense of beauty.”5 Henri Matisse said, “A work of art implies a harmony of everything together.”6 Paul Cezanne said that verisimilitude matters little and the harmony of form and color is the essential for great art.7 The opinions of these artists and philosophers concur with the conclusion drawn from the Unification Principle—that is, when harmony is achieved, a great work of art is produced.

There are two kinds of harmony: harmony in space and harmony in time. Painting, architecture, sculpture, handicrafts, calligraphy, and so on, are examples of harmony in space. In Greece we can find great spatial harmony in the ancient buildings and sculptures. Celadon porcelain (bluish green porcelain) made during the Koryo Dynasty in Korea, is one of the most famous examples of such harmony in space as far as handicrafts are concerned. Novels, poems, music, and so on, are examples of harmony in time; these forms of art express beauty through a passage of time. Whichever of the two kinds of harmony a work may express (dancing expresses both), harmony is what makes it beautiful.

D. The Relationship Between Beauty and General Values

Value usually refers to trueness, goodness, and beauty. Suppose there is an object and that it gives a certain stimulation to the subject. When that subject (a man) grasps an object’s stimulation with his intellect, it is called trueness. Man desires to obtain not only information, but also trueness. There can be falseness in information, but no falseness in trueness. In this case, man wishes to know trueness rather than mere information, and the stimulation from the object is now trueness. Scientists, also, study in order to obtain trueness, if possible, not just information and knowledge.

When the same stimulation is grasped by man’s will, it becomes goodness. Even things that have no will—such as plants and minerals—can be viewed as good, when grasped by will.

God created the universe, and on the sixth day He proclaimed everything as good. Since the universe was just as God had intended it to be, it was good. He appreciated it with His will; had God appreciated it with His intellect, He might have said, “It is true.” On the other hand, if He had appreciated it with His emotion, He might have said, “It is beautiful.” Depending on the way a man appreciates the same object, it becomes either true, good, or beautiful. Value, then as mentioned before, is appreciated differently according to which one of the three functions of the mind—intellect, will, or emotion—is emphasized. In this sense, value is decided upon by the reciprocal relationship between the subject and the object.

So far, the subjective element has been emphasized; nevertheless, there must be a latent (potential) element of beauty within the object itself. This element, when perceived by man, can give him the emotional stimulation that may result in the experience of beauty. A flower, for instance, has no active emotional function, but it can give stimulation. Since man receives the stimulation emotionally, it is the same as saying that emotion has come from the flower. Accordingly, we can say that beauty is produced by an emotional stimulation coming from the object.

IV. Types of Beauty

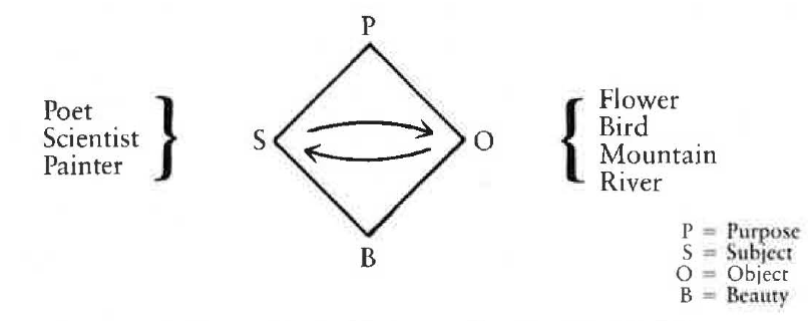

Beauty is determined by the give-and-take action between a subject (man) and object, centering on purpose. There are numerous kinds of objects, such as flowers, birds, mountains, and rivers; Accordingly, numerous kinds of beauty can be perceived. Furthermore, the same object displays different kinds of beauty when perceived by different subjects. Flowers, for example, are perceived by a poet differently from the way they are perceived either by a scientist or by an artist. When considering the varieties of quadruple bases, this diversity is inevitable. (Fig. 30)

A. Kant’s Classification of the Types of Beauty

Kant recognized two kinds of beauty: “grace” (Grazie) and “sublimity” (Erhabene). Grace can be subdivided into “free beauty” (freie Schönheit), “appendant beauty” (anhängende Schönheit) and “pure beauty” (Reinschöne). Free beauty is unrestricted, whereas appendant beauty is slightly restricted. Suppose there is a great variety of clothes, but only a few items that suit me. I consider those that suit me as especially beautiful, but the kind of beauty I see in them is dependent upon the restrictions of my limited purpose; hence, it is called appendant beauty. Pure beauty is that which contains moral elements, such as the beauty expressed in religious paintings. Sublimity is that which we feel when we see something great; it is a feeling of solemnity, awe, and reverence. In other theories of art one finds also “comic beauty” and “tragic beauty.” An example of “tragic beauty” would be a soldier going to the front line, risking his life for the sake of his nation.

Kant, as well as other theorists, was actually unable to set forth a solid philosophical standard for classifying beauty. Scholars generally make subjective classifications, based on their own experiences. A philosophical basis for classifying beauty, however, is necessary; this can be derived from the Unification Principle, as shown below.

B. The Unification Thought View of the Types of Beauty

In the Unification Principle, beauty and love are inseparable. There is no beauty apart from love. When considering the types of beauty, therefore, we need, first of all, to think about the types of love. Take parental love, for example. The more parents love their children, the more beautiful the children become. The relationship between love and beauty is reciprocal. When the subject loves the object, the love of the subject is perceived by the object as beauty. Reversely, when the object gives beauty to the subject the object’s motive (starting point) should be love.8 What types of love are there? There are three types of love in the Unification Principle: parental love, conjugal love, and children’s love. Then, what concretely are the types of beauty corresponding to the three types of love? I would like to clarify this question by explaining love more deeply.

Parental love is either paternal or maternal. When parents love their children, their love is perceived emotionalJy by the children as beauty. I visited a certain family some time ago, and asked the children, “Whom do you like best, your father or your mother?” They answered, “We like both.” “But whom do you like best?” I insisted. One child answered, “Father”; and another said, “Mother.” To like someone is to feel that he or she is beautiful. The children felt that their parents were beautiful because the parents gave them love.

Paternal love becomes paternal beauty for the children. Fathers do not always give their children tender, warm love. When the children are disobedient, fathers may punish, or scold, or frown at them. Although children may feel bad at that moment, they are usually thankful later. Strictness, also, can be an expression of love. Not only spring-like warmth, but also autumn- or winter-like strictness are expressions of the same love. This kind of love, also, may be felt as beauty by children. This may be called sublime beauty. Suppose a child makes a mistake and comes home fearing he is going to be scolded but his father forgives him saying, “That’s all right.” The child feels a certain kind of paternal beauty at that moment. It could be called beauty of generosity, which seems as wide a the ocean. In receiving various kinds of love from their father, children experience various kinds of beauty.

When we see the ocean, or majestic mountains, or a waterfall that cascades over a high cliff, we feeI a kind of awesome beauty. Where does this feeling come from? This type of beauty in nature is a modified extension of the paternal beauty we felt in our childhood.

Many people lose their father at a young age, but can still experience paternal love indirectly, through older relatives or friends, through teachers at school, or even through watching movies and television programs. I once saw a television drama in which a scientist and his son were kidnapped. Someone came to the rescue, but surprisingly enough, the child did not want to be rescued. He preferred to stay with the kidnapper because he was receiving more love from him than he had ever received from his father. The man who came to rescue them, however, treated the child also with love and kindness. So, he finally allowed himself to be rescued. That particular child had not received love from his father; yet he was able to experience paternal love from someone else. Children, therefore, can experience paternal love and paternal beauty, either directly, from the father, or indirectly, from another person.

Maternal love is different from paternal love. A mother is gentle, kind, and peaceful. Children perceive maternal love as what may be called peaceful beauty or graceful beauty. We may feel such beauty when we see, for instance, a statue of the Virgin Mary. After we have experienced such maternal beauty, we may feel it transformed into the peaceful beauty of the natural world.

With regard to conjugal love, a husband’s love for his wife is felt by her as masculine beauty; her love for him is felt by him as feminine beauty. Since everyone has a different character, there are a great number of different kinds of masculine and feminine beauty—among persons as well as in nature. Though there are cases in which the husband has an effeminate character, yet the wife can still experience masculine beauty, by observing it in other men. Reversely, there are cases in which the wife has a masculine character; here, also, the husband can still experience feminine beauty, by observing it in other women, through reading novels, watching plays and movies, and so forth.

What is children’s beauty? Children with a loving heart look beautiful to their parents. The original nature of a child is to make the parents happy. They do that through little things, such as showing their parents something they have painted or drawn, or making them laugh, or romping cheerfully about. This is children’s love; parents see it as charmingly beautiful. Sometimes children show their parents actions and gestures that are ludicrous and comical. This is “comical beauty.” As children grow, the beauty they express changes.

Once we have experienced children’s beauty, we can begin to perceive such beauty all around us. For example, young animals—such as baby chicks—are lovely; flower buds, also, are delicately beautiful. These things are extension of children’s beauty. In a family, the father sees the beauty of his children differently from the way the mother does. Similarly, a man and a woman probably see different aspects of the beauty of nature. In the family there is yet another kind of beauty, which comes from love among brothers and sisers; it is a kind of children’s beauty. The extension of such beauty can be found in nature as well. Our experience of beauty, therefore, is an extension of our experience of paternal, maternal, conjugal and children’s beauty. Since there are as many such kinds of beauty as there are individuals, there are innumerable kinds of beauty.

In summary, the types of beauty correspond to the types of love. Parental love is felt as parental beauty (paternal and maternal beauty); conjugal love, as conjugal beauty (masculine and feminine beauty); and children’s love, as children’s beauty (includjng brothers’ and sisters’ beauty). These three kinds of love are God’s love expressed divisionally through the basis of the family. Accordingly, beauty, as well as love, originates in God. This is the philosophical basis for the different types of beauty.

V. The Dual Aspects of Artistic Activity and the Dual Aspects of Purpose and Desire

Now I would like to discuss the philosophical basis for the activities of creation and appreciation. Looking at the world of artistic expression today, we have reason to be concerned. When people create and appreciate art, do they always have a truly aesthetic attitude? Can the activity of creation be totally separated from that of appreciation, and vice-versa? Why is creation necessary? Why is appreciation necessary? Are creation and appreciation compatible? These are a few of the many questions that require the establishment of a true philosophical foundation for art. The purpose of this section is (1) to show how the fundamental truth of the universe relates to creative activity; (2) to establish a solid philosophical foundation for artistic expression; and (3) to help creative persons find the right direction for developing their creative talents. As mentioned before, the Principles set forth here are based on the teachings of Rev. Sun Myung Moon, especially the Unification Principle. The section in the Principle entitled “Purpose of Creation” explains the reason why the universe was brought into being. God created man and all of creation in order to obtain joy from them; each created being has two purposes: the purpose for the whole and the purpose for the individual. In man’s case, the purpose for the whole is to give joy to God and to the whole (i.e., mankind, nation, society, and family, which represent God to him).

But God cannot be happy if man is sorrowful. When man is happy; God, also, can be happy. Man is created to be happy; this is the purpose for the individual. He wants to be happy not only by pleasing God and the whole, but also by seeking value from his objects—that is, creation and the persons in the object position to him. He should put the purpose for the whole first, and the purpose for the individual second. Some artists have a sense of mission in their work because they are unconsciously aware of this purpose for the whole. In the ideal world, all artists will have a similar sense of mission.

In order to achieve these two purposes, one must have will and desire. God, therefore, has given man the desires to realize value and to seek value, in order to achieve the purpose for the whole and the purpose for the individual. The desire to achieve the purpose for the whole is the desire to realize the values of trueness, goodness, and beauty. Man tries to serve the whole by living truthfully, by doing good deeds, and by creating beauty for others and for God. The desire to achieve the purpose for the individual is the desire to receive joy through obtaining values from one’s objects.

On one hand, man creates things with the desire to realize value, by which he tends to fulfill the purpose for the whole (man as a creator); on the other hand, he appreciates created things with his desire to seek value through which he tends to fulfill the purpose for the individual (man as an appreciator). Of course, man himself is pleased when he creates something, yet his primary purpose should be to please others with his creative works; this is from his desire to realize value. Furthermore, man feels joy by looking at the natural world, by admiring paintings, or by reading literature; this comes from his desire to seek value. We have always known that these kinds of desire exist, but perhaps have not clearly understood the reason why. This has now been explained.

VI. Requisites for Creative Activity

A. Subject Requisites (Artist)

1. The Establishment of Motive, Theme, and Plan

The first requisite is that the subject (artist) must have a purpose for engaging in creative activity. Just as the universe has the Purpose of Creation, so the work of art should have the artist’s own purpose of creation which is the motive. Rodin, for example, was inspired by Dante’s “Inferno” to design The Gate of Hell. He wished to create a figure of a poet overlooking the scenes of hell, meditating on the pain of hell fire and pondering upon what kind of life man should lead on earth . This is the motive for his sculpturing The Thinker in The Gate of Hell.

An artist, then, sets up a theme based on the motive. Rodin’s theme is a thinking individual. After determining the theme he still had to decide on how to express it. Would it be a sitting or a standing figure? Perhaps it was only after deep consideration that he decided to sculpt a sitting figure, with its back bent. This is the plan. With a concrete plan, he was ready to begin his work of art.

Millet, also, first established a plan for The Angelus, as do all artists in creating their works of art. The plan corresponds to Logos in the Creation process. The process through which an artist forms a plan for his work of art corresponds to the process of the development of the Logos within the Original Image. ln the case of painting, the plan must include all aspects of the work—color, form, size, etc. In abstract art, the theme of a work may not be readily apparent, as there is no attempt on the part of the artist to represent anything in the natural world. Instead, the theme is hidden, and it may be necessary to analyze the artist’s motive and plan quite thoroughly in order to discover it. The title of the work itself may be a helpful clue in this direction.

The motive or the purpose of creation, is established by heart, the emotional impulse. An artist’s way of thinking, individuality, interests, view of life, ideas, education and so on are engaged in making a plan. Accordingly, both an artist’s emotional element and an intellectual element are involved in the creation of a work of art.

Tolstoy said that art is the activity of transmitting the feeling of the creator. H. Read made an amendment to it and said, “The real function of art is to express feeling and transmit understanding.”9 They have expressed ideas along similar lines to the Unification Theory of Art.

2. The Attitude of the Artist (Object-Consciousness)

Now that the reason why artists have creativity (to achieve the purpose for the whole, through creation, and the purpose for the individual, through appreciation) has been clarified, we can also come to understand the attitude an artist should have in creating a work of art. This attitude may be called object-consciousness.

First, it should be an attitude of comforting the Heart of God, who has been sad throughout history. In other words, the artist’s creative works should be centered on God. Art is the activity of creating joy; its first requisite is that of being comforting to God. God, an artist Himself, endowed man with His creativity so that man, also, could create works of art. God created man and the universe in order to receive joy from them; accordingly, man’s first concern should be to please God. Owing to the Fall, however, artists, as a rule, have not thought of pleasing God in their creative activity. This is a sad thing for God indeed. Throughout history, God has endeavored to establish the Kingdom of Heaven on earth. He gave man creativity so that man might play an important part in building the Kingdom. Because of the Fall, however, numerous artists have not believed in God, which has been a cause of grief for Him. Artists, therefore, must endeavor to comfort the historically sad God.

Second, the artist should comfort Jesus and the saints, who were persecuted by fallen people. To comfort them, now in the spirit-world, is to comfort God, who sent them to people on earth in order to realize the Kingdom of Heaven.

Third, the artist should record and publicize the good, virtuous, and righteous deeds that are being performed now or were performed in the past. Innumerable good deeds have been done, but most of them have been disregarded by sinful man. Actually, a great number of righteous men were miserably persecuted, not only in the past, but also in the present. Such good deeds are surely still being performed. Artists, therefore, should attempt to portray them in their works; by doing so, they will be cooperating with the providence of God and helping to counter the tendency of today’s mass media to publicize only man’s evil deeds.

Fourth, the artist should proclaim the coming of the ideal world, having firm confidence in the future. Without such an attitude, his works will not be as beautiful as they possibly could be. In the Renaissance, for instance, artists usually displayed a great deal of hope and idealism—which many of them derived from a strong faith in Christ.

Fifth, artists should try to give glory to God by depicting the wonders of nature. God created nature in order for man to have joy upon seeing it. Because of the Fall, man has been unable to really see beauty in nature. If he had perfected his personality through completing the first blessing—thus becoming the perfected object of God—man would have been able to see the brilliant and wondrous side of nature. Flowers, trees, rivers, etc., would have looked exquisitely beautiful. Nature is the manifestation of God’s attributes; artists, therefore, should portray nature so as to manifest God’s mysterious, profound, and wondrous attributes, giving Him glory and returning deep thanks to Him for bringing nature into existence.

Good works of art are created only if the artist has a fundamental attitude of serving the whole and pleasing others. Undoubtedly, a lot of fine works of art created during the Renaissance have this object-consciousness. Actually, a great number of artists of that period were pious people. Raphael, for instance, made use of religious themes in a large number of works; Michelangelo did likewise and produced famous works, such as The Last Judgment. They painted those works of art in order to give glory to Jesus and to God, as well as to help the development of Christianity. This is object-consciousness. For this reason, I think they received a great deal of cooperation from the spirit-world. The highest form of object-consciousness is to wish to offer glory to God, the supreme Subject.

3. Individuality

Man is a being with individuality, created resembling a particular Individual Image in God; individuality, therefore, is an essential characteristic of the original human nature, as explained in “Theory of Original Human Nature.” Accordingly, in the creation of a work of art, the individuality of the artist should be expressed, since the work is a manifestation of the artist himself. Man’s purpose includes the free display of his individuality, in order to please God; this is especially true of artistic activity. Artists should fully display their God-given individuality, so as to please God and mankind. Thus, even though maintaining an object-consciousness, artists can, nevertheless, express their own unique personality and ideas.

B. Object Requisites (Work of Art)

The harmony between the Sung Sang and Hyung Sang elements is the most important requisite for the object. By Sung Sang elements I mean the motive, theme, and plan; by Hyung Sang elements, such things as shapes, lines, and material elements. In Rodin’s The Thinker, for instance, Hyung Sang elements would be such things as the head, the back, the chest, the curved lines, and the material element (bronze). Collation should take place between the Hyung Sang elements and the motive, theme, and plan. Of course, the Hyung Sang elements themselves should all harmonize with one another to create a well-harmonized whole.

When the artist sees harmony between the Sung Sang and the Hyung Sang elements, as well as among the various elements within the Hyung Sang, he experiences beauty and joy. This is because the harmony of the elements within the object (work of art) resembles the harmony of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang and the elements within the Hyung Sang, of the artist himself.10

The terms “content” and “form” are often used in art. In this context, content corresponds to motive, theme, and plan (Sung Sang elements); and form, to the material elements (Hyung Sang elements). The harmony of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang elements, therefore, can be expressed also as harmony of content and form. As mentioned above, artists have various viewpoints about art; yet many of them agree that balance and harmony are the most important characteristics of a fine work of art.

C. The Technique and Method of Creation

1. Technique

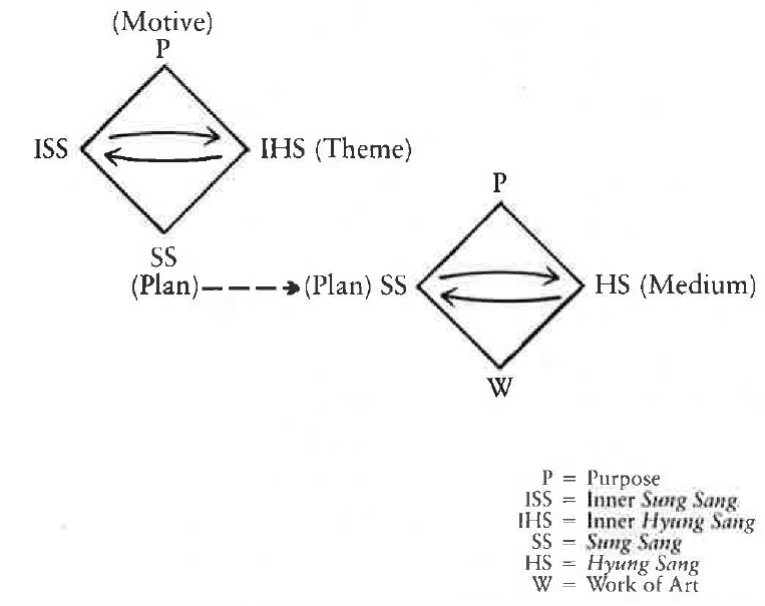

Technique corresponds to the skill in expressing beauty according to the two-stage structure of creation. The two-stage structure means, first, that the Logos is formed through the give-and-take action between the Inner Sung Sang and Inner Hyung Sang centering on purpose, and second, that an art work is created through give-and-take action between the Logos and Hyung Sang, centering on purpose. We have, therefore, an inner quadruple base and an outer quadruple base. Whenever creative activity—such as manufacturing in a factory, the ploughing of fields by farmers, or research by scholars—takes place, skill is always applied, according to this two-stage structure of creation.

Since there is Purpose within the two-stage structure of the Original Image, purpose is necessary in the creation of an art work as well. Why are motive, theme, and plan necessary? Because they were also necessary for God. In the created world, all phenomena, except those originating from the Fall, came from the Original Image. When God created the universe, He had an irrepressible impulse to create an object of joy. This was His motive for creating the universe. Then what should He create? He decided to create man in His likeness. This was His theme, the idea of man. Then he pondered upon where to put the head, eyes, legs, internal organs, and so forth. This was the plan, or Logos. Finally, He created an actual man through give-and-take action between His plan, or Sung Sang elements, and the appropriate Hyung Sang elements.

Man is God’s masterpiece. God gave man the ability to create his own object of joy by giving him even His Creativity. Probably God would have said to man, “Have motivation as I have, have your own themes, and create.” A true artist uses all the creative powers at his command to create a work of art, because that is what God did in creating man. Since man is made in the likeness of God, he has an irresistible impulse to conduct his creative activities following a pattern similar to that established by God.

2. Formation of the Outer Quadruple Base

Technique, in the context of creative activity, refers specifically to the skill to form .the outer quadruple base (i.e, the second stage of the two-stage structure of creation).

In the formation of the quadruple base, materials are necessary. There are two kinds of materials: subject-matter and medium. The subject-matter corresponds to the theme and is referred to as the Sung Sang material; the medium corresponds to physical materials employed and is referred to as Hyung Sang material. The formation of the outer quadruple base means the preparation of Hyung Sang materials to actualize the plan.

An author uses his experiences, imagination, or actual events as his subject-matter. A sculptor sometimes uses a model as his subject-matter; he needs marble, or wood, or some other material, as well as tools. A painter needs paint materials, brushes, canvas, an easel, and so forth. These physical materials are the medium (Hyung Sang material) in the second stage of two-stage structure of creation. Furthermore, the quality and quantity of physical materials must be decided upon: how much marble to use, how hard it should be, what kind of gloss it should have, etc. (Rodin’s works, for example, have considerable gloss.) As we can see, the artist must take into account a large number of factors when choosing his materials. This is the preparation of the Hyung Sang.

To create the actual object of art, an artist must perform give-and-take action between the plan (Sung Sang) and the medium Hyung Sang). For example: in painting, the artist performs give-and-take action with brushes and other materials, while following a plan.11 In order to carry out this give-and-take action harmoniously, artists need to develop skills—which means that they need art education. (Fig. 31)

3. Method

Method is the way of realizing the two-stage structure of creation. The first stage is when the Inner Sung Sang and Inner Hyung Sang, centering on the purpose, engage in give-and-take action. Variety comes about if any of the three factors—that is, purpose, Inner Sung Sang, or Inner Hyung Sang—is changed. Of course, if the Hyung Sang (medium) of the second stage is changed, the work will vary also.

Suppose we decide to paint a certain autumn scene. One person might paint the red leaves of a maple tree; another, a lonely scene of trees without leaves. The Inner Hyung Sang (theme) varies, depending on the artist. Even though the theme is the same, the substance of each picture is different, influenced by the individuality, or style (which is related to the Inner Sung Sang), of the artist.

Artistic expression, therefore, can vary endlessly, according to the artist’s individuality. If, for instance, other sculptors had been assigned the task of creating a statue similar to Rodin’s The Thinker, each statue would have been different. Nevertheless, different kinds of artistic expression often share common characteristics, and thus may be classified under various styles. I would like to say a few words in explanation of the main styles and their characteristics.

(a) Realism. Realism is usually called 'actualism' in philosophy. Realists try to express the object photographically, with precision and vividness of detail. Realist art tends to be intellectual, real, and objective.

(b) Idealism. Artists of idealism do not paint things as they appear, but select only those elements that suit their motive or theme. In painting a man, for example, they paint an idealized man, one worthy of respect, who may be, however, a vulgar person in real life. Many works of art in the Renaissance are examples of Idealism. Tolstoy and Lee Kwang-Soo, for instance, may be called idealists.

(c) Expressionism. Expressionists try to manifest their own views about life, as well as their thoughts, ideas, and emotions, through artistic works. They express what is in their minds, rather than objects as they appear to the eyes. Thus their style has a tendency to be subjective. The works of Van Gogh and Edward Munch are examples of Expressionism.

(d) Classicism. Classical art was popular in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Classical artists respected the arts of the ancient Greeks and Romans and tried to continue in the same style. Classicism respects intellect, universality, harmony, and completion—and attaches great importance to form.

(e) Romanticism. Romantic art, popular during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, was just the opposite of Classicism. Romanticists expressed man’s dreams of an ideal. Passionate love between man and woman is a common theme, and the term ‘romantic’, used today to refer to this love relationship, comes from Romanticism. Artists attached more importance to content than to form. A representative writer of this period is Byron. Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Goethe’s Faust, also, are examples of Romantic style.

(f) Symbolism. Symbolism, a movement that began in France at the end of the nineteenth century in reaction to the rigidity of naturalism and realism, expresses subjective feeling (emotion) in symbols, rather than depicting objects as they appear. Lyricism in poetry belongs to symbolism.

(g) Impressionism. The impressionist movement in fine art, at the end of the nineteenth century, sought to convey the brightness of a fleeting impression of a scene through the use of points of primary colors. Instead of depicting the natural colors of things, impressionist painters allowed the observer’s eyes to mix the colors on the canvas and thus form the color of the objects depicted in the painting. In this way, impressionist paintings create an impression of freshness and life. In literature, impressionists portray a subjective and sensuous impression of things in the natural world. Monet, Pissaro, and Sisley are representative impressionist painters.

Other styles, such as Cubism, Fauvism, and Surrealism have developed in the twentieth century, but I will not deal with them here. From the styles mentioned, we can see that if the methods of expressing something are different, the same theme will be expressed in a different manner. Why do the various styles appear? Philosophically, it can be said that when the four factors—that is, purpose, Inner Sung Sang, Inner Hyung Sang, and Hyung Sang—change according to the artist, the result (here, the work of art) cannot but change as well. This is the reason for the appearance of the different schools of artistic style.

VII. Requisites for Appreciation

Art has a close connection with ethics, since love and beauty are complementary. Ethics refers to the practice of love, while art is the creation of beauty. The practice of love is realized on the basis of the harmony between the spirit-mind and the physical mind. The spirit-mind seeks to attain the values of trueness, goodness, and beauty; the physical mind pursues physical things, such as food, clothing, and shelter. The two minds have a subject–object relation ship. Thus, the first requisite for appreciation is a harmonious relationship between the spirit-mind and the physical mind of the appreciator. In other words, the appreciator must lead an ethical life, approaching art with a pure mind, free from mundane trivialities.

Upon this foundation, the appreciator must also have his own way of thinking, individuality, interests, hobbies, view of life, ideas, education, and so on. He needs a basic understanding of culture in order to understand art in any real depth. Of course, even if he knows nothing about it, he may still feel beauty, but not very deeply. In addition, his interests and hobbies should be congruent with the work of art; if they are not, it will be difficult for him to feel beauty, since appreciation involves the aspect of creativity. Heart and love, which are prerequisites for artistic activity, should be considered as well; these qualities will enable the appreciator to be emotionally stimulated by the right kind of atmosphere. In fact, art galleries are so constructed as to provide a conducive atmosphere for the appreciator, for one cannot easily appreciate art in a crowded or noisy environment.

Another requisite is that the subject should have a healthy physical body (Hyung Sang). Though he need not have unusual strength, he should, at least, have sound optic and auditory nerves in order to judge beauty, for he appreciates a work of art with his eyes and ears. It is very difficult fully to appreciate a work of art—no matter how splendid it may be—if one’s physical capabilities are impaired. Beauty is determined through harmonious give-and-take action between the work and the appreciator. The appreciator will be able to enjoy art only to the extent that he has these requisites for appreciation.

As I have said before, creation and appreciation are not entirely different. Creation is closely related to will, and appreciation, to intellect, but both activities are performed centering on emotion. Will and intellect cannot be separated, so there is appreciation in creation, and creation in appreciation. A painter feels beauty by appreciating the picture while he is in the act of painting it. In appreciating the object, the appreciator modifies it into something more beautiful, by adding his own subjectivity to it, which is a kind of creation. Thus, creation and appreciation are divided, in this explanation, only for the sake of convenience.

The one who appreciates works of art must have Sung Sang requisites, as explained above. At the same time, he must understand the Sung Sang aspect of the creator. The artistic work can best be understood when the Sung Sang aspect of the appreciator and the Sung Sang aspect of the work of art are united. Beauty does not appear without resemblance. Since the appreciator has harmony within himself, he may feel the beauty of a work immediately upon seeing it; if he wants to feel beauty more deeply, however, he needs to understand the Sung Sang aspect of its creator.

Once created, a work of art cannot be transformed to be the way the appreciator wants it to be because it has already been completed. In order for harmony and unity to come about between the Sung Sang aspect of the appreciator and the Sung Sang aspect of the work, the appreciator himself must endeavor to attain a closer resemblance to the work. That’s why it becomes necessary to understand the creator’s way of thinking, planning, etc.

The subjective action already explained in this chapter is also significant in the appreciation of a work of art. An appreciator creatively adds his own way of thinking, individuality, ideas, and so on, to the work of art, in order to establish a closer resemblance between the work and himself.

VIII. Unity in Art

Artistic activity is, in a word, activity of unificati on. Art is the unity of various correlative activities and elements in creating beauty. There are several kinds of unity, which can be classified as follows.

A. Unity of Creation and Appreciation. Creative activity and the activity of appreciation in art should be carried out in unity. I have explained this already.

B. Unity of Content and Form. When the content, of the Sung Sang elements of motive, theme, plan, etc. are in accord with the form, or the Hyung Sang elements of line, form, color etc., a fine work of art is produced. Thus, content and form should be one.

C. Unity of Universality and Individuality. An artist himself is the unity of universality and individuality. He can be a Japanese and, at the same time an individual named Takahashi. As a Japanese, he has characteristics common to Japanese people in general—including customs and language—and, at the same time, his own individuality. If he paints a picture, and if the style of painting in Japan tends toward romanticism, for example, he will probably paint in a romantic style; within this style, however, he will express his own individuality and character. Universality and individuality, therefore, are united in his person, as well as in his work.

Japanese art has been influenced by other cultures in different periods of history. Greek artistic influence, for example, appears to have entered Japan by way of India, China, and Korea. Greek art was internationally influential, and so corresponds to universality. After entering Japan, it was integrated with indigenous art; thus, we can say that Japanese art, also, is a unity of universality and individuality.

The relationship between the unified culture and national cultures will be important in the future. Communism says that destruction is inevitable when constructing something new, which means that old traditions would have to be annihilated upon global communization. If that were God’s way, He would have destroyed mankind after the Fall and created a new Adam. We know, however, that He could never have done such a thing. On the contrary, He has worked to restore them and to build a new world based on the Principle. In the same way, we will create a new culture by preserving existing cultures and restoring them.

The basis for the unity of universality and individuality, according to the Unification Principle, is that one of God’s own attributes is the unity of the Universal Image and the Individual Image. Thus, every created being, also, is the unity of universal and individual images. Because man’s way of creating a work of art resembles the way God Himself creates, universality and individuality appear also in man’s works of art.

D. Unity of Eternity and Temporality. Historicalness is another word for eternity in a work of art, and actualness is another word for temporality. The unity of eternity and temporality can be seen in Millet’s The Angelus. The church and the scene of the people praying represent the eternal (historical) aspects of the painting; the countryside and the landscape—which are peculiar to a certain period and region—represent the temporal (actual) aspects. Their clothes, also, can be seen as part of the painting’s actualness or temporality. In this way, historicalness and actualness are united in The Angelus.

Let’s take another example. Suppose there is a vase with beautiful roses arranged in it. The unity of eternity and temporality is also expressed there. The beauty of roses is unchanging, and the form of a rose is the same now as it was in the past and will be in the future. On the other hand, the unique arrangement of the roses, as well as the vase that contains them, are peculiar to the present time and may be seen as the aspects of actualness, or temporality. Thus seen, the vase and the roses are an example of the unity of eternity and temporality. When we realize this, we can appreciate their beauty even more deeply.

IX. Art and Ethics

Creation and appreciation are activities of dominion. If man had not fallen he would have grown through the three stages of formation, growth, and completion and would have been given authority of dominion by God. To grow is to perfect one’s individuality, and to perfect one’s individuality means to become fully united with the Heart of God, or to perfect one’s personality. In other words, it is to become an ethical person by experiencing God’s love. Such a man is given the right of dominion. True dominion is dominion through love. For this reason, the practical activity of art is inseparably connected with ethics.

Even fallen men have known this and, to a certain extent, have attempted to acquire this ethical aspect of personality. Since, however, they had little philosophical understanding of why artists, also, should be ethical, they sometimes became discouraged. When in financial difficulties, they would often brush aside their ethical principles and produce works that could be sold easily. Man is to be given the authority of dominion after having grown through the formation, growth, and completion stages. Only when artists understand this in detail will they seriously endeavor to become truly ethical.

Numerous artists have dealt with themes of love in their novels, plays, movies, and other art forms, but very rarely were the artists themselves persons of high ethical standards. In fact, a great number of them spent their lives wantonly. Oscar Wilde, for instance, a well-known writer of the nineteenth century, was a typical case: he pursued immoral love and was put in prison for violating the law. In the Unification Principle view, the kind of love mundane artists have usually portrayed is not God’s love, but fallen love—that is, the fallen love of the archangel, who deceived Eve, as well as the fallen love of Eve, who deceived Adam. As a rule, artists have done nothing but modify and embellish fallen love—though some of them have sincerely tried to express original human nature and original love.

Accordingly, artistic beauty has been expressed on the basis of fallen love, not of true love, or God’s love. Only when artists realize God’s love in their lives—that is, when they realize the unity of art and ethics—will they be able to create a true work of art.

X. Critique of Socialist Realism

Socialist realism in the communist theory of art stresses expressing things as they really are. Communists say that artists in the capitalist society will not express contradictions within capitalism, but will only express its good qualities, idealizing them. They are, therefore, idealists and romanticists. Socialist realism demands that artists express the conflict between capitalists and laborers, or the miserable lives of laborers and farmers. Socialist realism asserts also that an artist should create in order to help realize a socialist society; that is, he should help to incite public antipathy toward the capitalist society, and lead people toward the socialist ideal.

Lenin said that all literary men should commit themselves to the Party. Stalin said that artists are the engineers who reconstruct men’s minds. Gorky, a Russian proletarian writer who was awarded the Stalin prize, said that a writer is a teacher of the proletariat, and that an artist is a gravedigger who buries capitalism, as well as a midwife who helps give birth to socialism. Proletarian art is well and truly under the control of the Communist Party.

Although modern communist art pretends to depict man’s original nature, in fact it does not. The communist philosophy of art can never change, because it is based on communist ideology. Under communist regimes, some artists may express divergent views of art, but they are not considered as being representative of the proletariat.

According to historical materialism, art, being a part of social life, is supposed to belong to the superstructure. Since the superstructure is based upon a foundation, it changes when the foundation changes. Communist theory claims that it is the duty of the newly built superstructure to nourish and protect the development of the new foundation and help destroy the old foundation. The foundation consists of the production relations—i.e., the social system. Socialist art, therefore, should contribute to the preservation and development of this newly established social system.

This assertion is based on the materialist idea that spirit comes from matter. The communist theory of art, also, is based on this idea; as long as communists have this idea, art will be a tool for realizing a communist society. It is a lie to say that their art is for the protection of democracy. If they wanted to protect democracy honestly from the bottom of their hearts, they would have to announce that they are giving up the whole of communistic thought, because the principle of democracy can never be produced from communistic materialism and the dialectic. They would have to confirm publicly that their theories of “dialectical materialism,” “historical materialism,” and other theories based on Marx’s Capital, Communist Manifesto, etc., are all quite mistaken. But then they would also have to do away with the name “Communist Party,” because when they have given up their whole system of thought, the name “Communist Party” becomes devoid of meaning.

Pasternak took part in the Russian Revolution, putting much hope in communism. He later realized he was wrong, and it was then that he wrote Dr. Zhivago. The communists criticized him severely, calling him “a bourgeois writer,” and a “reactionary element.” Although he received a Nobel Prize from the free world, he and his work were criticized by the communist world as being evil and ugly, obviously from completely different standards of value.

H.E. Read criticized the Soviet Union, saying that it is wrong to compel someone to create a work of art in support of a certain dogma. G. Mittal, in India, said that Communism is the major enemy of man’s freedom of thought. Ehrenburg, who once received the Stalin prize for Peace, later regretted accepting it. He criticized the writing of one of his friends, which depicted a girl in a textile factory, saying that the girl described in the book was like a machine, with no personality. It is true that people in the Soviet society are regimented and have very narrow scopes within which to develop their individuality.

Andre Gide wrote the famous Return from the U.S.S.R., after his trip to the Soviet Union. He observed that wherever he went people would give him the same answers to his questions. This showed him that their freedom was restricted. We cannot accept that Soviet art is the honest expression of an individual’s heart.

I would like to criticize Soviet art from the standpoint of the Unification Principle. In one of his books, Marx admits that he found some difficulties in his theory. In his words,

The difficulty we are confronted with is not, however, that of understanding how Greek art and epic poetry are associated with certain forms of social development. The difficulty is that they still give us aesthetic pleasure and are in certain respects regarded as a standard and unattainable ideal.12

According to Marx, therefore, art is a part of the superstructure and develops on the basis of the economic foundation. So, the superstructure, theoretically, can never remain, after the foundation has been changed. Throughout the two thousand years since the Greek downfall, however, the foundation (social system) has changed several times, whereas some elements of the superstructure (for example, interest in art) did not change. This is the difficulty to which Marx refers; it is counterevidence to his theory of history.

He said that Greek mythology—such as Homer’s epic poems Iliad and Odyssey—can still be aesthetically pleasing to persons living today. According to his historical materialism, the superstructure, including our interest in Greek art, should have vanished completely by now, since the foundation of Greece was completely destroyed long ago. Nevertheless, our interest in Greek mythology remains.

This means that his philosophy, including his theory of art, is wrong. His consideration that art belongs to the superstructure, which is built on an economic foundation, is quite mistaken. He cannot but be mistaken, because his theory is based upon materialism which asserts that spirit comes from matter. The shortcomings of this notion have already been pointed out in other parts of this book. His theory of art loses its credibility with the loss of the credibility of materialism and the dialectic.

Seen from the standpoint of the Unification Principle, human history has been the history of struggles between good and evil, because of the Fall. The goal is the ideal world, the Kingdom of God. Human history is the history of restoration. Although man has not been conscious of it, God has been working through man’s conscience to lead history in the direction of righteousness, goodness, and love.

We can regard the Trojan War, for instance, as the struggle between good and evil. In the Odyssey, Odysseus found, upon returning home, that his wife had been faithful to him during his ten-year absence after the Trojan War. Several men had attempted to seduce her and to take her away, but she remained chaste to the last. This is a story of righteousness. In making the effort to remain faithful to her husband, she went in the direction of restoration. We unconsciously know that God’s providence has continued in every period of history, and feel joy to hear stories of faithfulness that are in accord with it. Although Lenin banned the works of Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and others, factory workmen read them in secret. Why do they read them? Stories about people who walked the way of restoration and suffered a great deal in pursuing trueness appeal to man’s heart. These books contain such stories.

Notes

1 Herbert Read, The Meaning of Art (Faber & Faber, London, 1968), p. 18.

2 Divine Principle, 2nd ed. (HSA-UWC, New York, 1973) p. 42.

3 Ibid, p. 46.

4 Ibid., p. 47.

5 Herbert Read, The Meaning of Art, p. 35. tibid., p. 264.

6 Ibid., p. 264.

7 Ibid., p. 200.

8 Accordingly, the relationship of love and beauty is that of inner and outer, and so the types of beauty can be said to correspond to the types of love.

9 Herbert Read, The Meaning of Art, p. 266.

10 In the next section of this chapter I will discuss what takes place in the process of appreciation.

11 This type of give-and-take action, whic h occurs between a conscious party (the artist) and an unconscious one (paint, brush, etc.), will be further discussed in “Methodology. “

12 Marx, A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1977),p. 217.