11 Methodology

Man lives in a complex world, amidst complex phenomena, both natural and social. In order to find a way to live in the most advantageous fashion in this world, he needs understanding—that is, correct knowledge and correct cognition. But how should he go about obtaining it? What methods should he use in his search Heraclitus truth? These questions lead us to the subject of this chapter: methodology.

Scientists develop methodologies for their respective fields; every philosophical system, also, has a characteristic methodology. Marxism, for example, developed materialistic dialectics, claiming that it is the law of development of nature, society and man’s thinking.

What place does methodology have in Unification Thought? It is at the very base of it. Through methodology, certain fundamentals of the Unification Thought view are established. The problem of how things should exist and should relate among themselves; how man thinks; how he should dominate the creation; how he goes about finding the truth, and so on, are all questions to which Unification Methodology addresses itself.

In this chapter we will, first, investigate a few of the most representative approaches set forth in the history of philosophy; next, we will compare them with Unification Methodology; finally, and as a result of this process, we hope to clarify our viewpoint on these important issues.

I. Historical Approaches

A. Heraclitus (c535–c475 B.C.)

-The Dialectic (Dynamic Method)

Heraclitus, a Greek philosopher, is sometimes called the father of the dialectic. He considered arche (original substance) to be “fire”. All natural things, he asserted, are changing in a process of constant mutation. As one person is born, another dies. Everything is changing because of struggle.

In his methodology, Heraclitus was chiefly concerned with the problem of how nature exists and develops. Though he recognized harmony in nature, Heraclitus, nevertheless, advocated a concept akin to the dialectic, since, in his view, struggle is the cause of development in nature. His method can be called dynamic method, since he tried to catch the dynamic aspect of things.

B. Zeno of Elea (c490–c430 B.C.)

-The Dialectic (Static Method)

Zeno is usually called Zeno of Elea to be distinguished from Zeno of Citium (c336–c265 B.C.), the founder of Stoicism. Zeno of Elea supported Parmenides (the founder of the Eleatic school of philosophy) in opposing Heraclitus’ view that everything is changing. They argued that everything that really exists is unchangeable, being neither born nor destroyed. Existing beings seem to move, but actually do not; they seem to be born and destroyed, but actually are not; they seem to change, but are in fact unchangeable.

Zeno sophistically demonstrates this with his famous “Paradox of the Flying Arrow”. An arrow flies from point A to point C. In doing so, it passes through point B. When it passes through point B, however, it stops there. There are actually infinite such points between A and C, so the arrow must continuously be at repose. Even though the arrow is seemingly moving, in fact it is not moving, but is stationary.

Zeno gives another illustration, the story about “Achilles and the Tortoise”. Achilles, hero of the Trojan War, was very fleet-footed, but could not outstrip a tortoise. Letting it get a head start, he ran to the place where it had been when he started, but it was no longer there. Seeing it ahead of him, he ran to that place, but again it had gone a little further. Each time he reached the point where it was before, it had gone a little further. The tortoise, finally, won the race. This story, also, is very sophistic.

Marxism has a ready answer for the puzzle of the arrow: it is moving, and is at the same time stationary. If an arrow is stationary at any point, it is always stationary, and if it is not (i.e. if it does not exist at any point), there is no movement at all. Such an impasse can only be resolved by the dialectic, i.e. by the unity of repose and motion, Marxists hold. This is more sophisticated sophistry than Zeno ever managed to produce.

Time and space exist in a correlative interaction, just like Sung Sang and Hyung Sang. One cannot exist without the other. Movement, therefore, cannot exist without time and space. Assuming that time is T, and distance (space) is S, we can say that the velocity of a movement V = S/T. If we think, here, of such a point as has no space (i.e. S equals zero), time T necessarily becomes zero, and the equation becomes meaningless.

Accordingly, in the discussion of an arrow’s going through a point, we must consider a point which has definite space, however small it may be, since a mathematical point which has position but no size, does not exist in the physical world, but only in the world of thought. It is fallacious to combine an abstract point with actual motion.

The movement of a substantial being should be examined within a definite time and space. Then we can conclude that the flying arrow is moving at a point, since it moves through an infinitesimal space in an infinitesimal time. It is neither stationary at a point as Zeno asserts, nor stationary and moving as Marxism asserts.

As for “Achilles and the Tortoise”, Zeno reaches such a sophistic conclusion, because his discussion is limited to space only, neglecting time.

Zeno’s method was considered dialectical by Aristotle. It is called idealistic dialectic, or subjective dialectic. To Zeno, the dialectic was a debating device; he persuaded others by pointing out the contradictions in their arguments.

But, it is important that we do see an unchanging, or eternal, aspect in every being. There is, therefore, some validity in Zeno’s speculation. We may call his approach the static method.

C. Socrates (469–399 B.C.)

-The Dialectic (Dialogic Method)

Socrates deplored the fact that the sophists of his day prospered by confusing people’s minds. The Sophists said that, even if nature has objectivity and necessity, human problems are relativistic, so there is no objective truth in human society. Truth depends on time, place and man. Truth may be untruth; it is a matter of expediency. In the midst of a confused society, Socrates maintained that people must talk to each other with sincere hearts. Sophists pretended to know much, but knew nothing. “Know thyself!” he said. We cannot arrive at an ultimate, universal truth until we recognize that we really know nothing and begin to engage in earnest and sincere dialogue with one another.

D. Plato (427–347 B.C.)

-The Dialectic (Classification of Idea)

Plato’s method is dialectical. His dialectic is the method of connecting Ideas to form a hierarchy of Ideas—that is, the method of dividing the world of Ideas.

Plato maintained that what really exists is Ideas, the physical world being made up of shadows of Ideas. Ideas develop into substantial entities. In the world of Ideas there is no disorder, but a hierarchy, or stratified structure. In the same way that numerous cells are gathered to form the structure of man, numerous Ideas are gathered to form the hierarchy of Ideas. Just as scientists acquire knowledge about the physical world by analysis and synthesis, we can do likewise with the world of Ideas, by applying the dialectical method.

In the hierarchy of Ideas, the Idea of Good occupies the highest position (instead of God). The development of the universe has purpose—that is, the purpose of reaching goodness. Plato was the first thinker with a teleological cosmology.

E. Aristotle (384–322 B.C.)

-The Deductive Method

The deductive method of Aristotle remained unchallenged for almost two thousand years. This method starts with a universal truth and then tries to arrive at concrete conclusions by analyzing this truth. The deductive method can be seen in the following example of a syllogism: (i) All men die; (ii) Socrates is a man; (iii) Therefore Socrates will die. Another example is (i) All beings with mass respond to gravity; (ii) An apple has mass; (iii) Therefore an apple responds to gravity (i.e., will fall to the ground from a tree). This may seem quite obvious, but it illustrates that the deductive method is used as a means to ascertain concrete facts from universal truths. There is a lot of truth in it, so it has been universally recognized.

In the Middle Ages, theology reigned supreme. That God created all things was the universal truth. All beings were His creatures. All things and phenomena were explained from the universal truth that God created the whole of nature and humans. The deductive method was a useful aid for theological arguments, so it did not undergo any alterations, but remained unchallenged all through that period.

F. Bacon (1561–1626)

-The Inductive Method

The Renaissance was the beginning of scientific development, and a challenge to dogmatic deductivism. Francis Bacon maintained that the only way to gain new knowledge from nature is through experimentation and observation, and that it is impossible to obtain it through speculation, i.e. through the deductive method. If I already know for certain that all men are mortal, for instance, then when I say that an individual will die I am not stating anything new; this is not new knowledge, but an obvious fact.

Bacon maintained that we should throw away prejudices in order to gain true knowledge and insights. He called these prejudices that we all harbor Idola (Idols), of which we have four types: Idols of the Tribe, Idols of the Cave, Idols of the Market Place, and Idols of the Theater.

The Idols of the Tribe are the prejudices of the human species; illusions of the senses, and the tendency to personify things. Because of this, people once thought that when a rock fell over a cliff, some great manlike power might have pushed it.

The Idols of the Cave are the prejudices which come from individual customs, opinions and education. This is the attitude of judging everything based on one’s own narrow view of life.

The Idols of the Market Place are the prejudices which come from the inaccuracy of the words men use in daily life. They sometimes use words which indicate things that do not exist at all.

The Idols of the Theater are the prejudices of authority. People are apt to believe blindly the various philosophical treatises which represent worlds of their own creation; i.e. theaters.

Bacon asserted that, after taking away such Idols, we should make observations and experiments on nature, and obtain by abstraction the general concept of the things. This is the theory of induction.

G. Descartes (1596–1650)

-The Methodical Doubt

After he had doubted all things, Rene Descartes realized that what he could not doubt was that he was thinking. Reason, or thinking, finally became a surety for him, so he maintained that reason is the only subject of cognition in which we can believe. Methodical doubt is to seek to obtain truth by doubting all things, especially experiences. From this method came rationalism.

Descartes doubted the certainty of all existence, except the fact that he was thinking. He went on with his thinking, and decided that what is clear and distinct in thinking is certain, because God guarantees it. We can only say this, however, if we accept that God exists. Does God exist? Descartes said that man knows the idea of God naturally (a priori), and that the idea of the perfect Being, the idea of God, cannot come from the imperfect being, man, therefore God exists.

I think that it is not unreasonable to say, “I think, therefore I am” (cogito, ergo sum), because there is no one who doesn’t think, but to assert that God exists from the above reasoning is dogmatic, for not all people think of God, and among those who do, there are endless disagreements about what or who God is. The rationalism, in which experiences are considered unimportant, fell into dogmatic metaphysics when it came to Wolff through Leibnitz.

H. Hume (1711–1776)

-Idealistic Empiricism

When empiricism came to David Hume, it turned into skepticism. The knowledge obtained from scientific observations seem to be true, but may not actually be so. Suppose we see a flash of lightning and hear a peal of thunder a few seconds later. Light and sound are completely different. We see light with our eyes, and hear sounds with our ears. Nonetheless, we think that the sequence is causal, because one comes before, and the other follows it. But how about a cock crowing just before dawn? Can we say that the sun rises because the cock crows? Of course not!

We can only say that the relationship between lightning and thunder—like that between the cock and sunrise—is one of before and after. To say that the relationship is causal is to insert our own subjectivity into the judgment, a mistake we often make.

There is also the matter of “substance” (substantia, ousia). We should not assume that the substance of a flower exists. We do not feel the flower itself, but only experience its color, shape, aroma, etc. With our eyes, we see its color and shape; with our nose, we smell its aroma; with our hands, we touch its softness. Only the perceptions (impressions and ideas) coming from these sensations actually exist; existence is nothing but a bundle, or collection, of perceptions. We cannot, therefore, say that the substance of a flower—or of anything—exists in reality. Starting with empiricism, Hume became skeptical, for he doubted the existence of objective beings which are independent of the subject and are the source of experience.

I. Kant (1724–1804)

-The Transcendental Method

Immanuel Kant wanted to unite rationalism and empiricism, since both have good points. He said that both reason and experience (subject and object) are necessary for cognition, since forms of intuition and forms of synthesis come from the subject, whereas sense-impressions come from the object.

The attributes of an object reach our senses in the form of sense-impressions (content), yet this is not enough for us to recognize the object. We need ‘forms of synthesis’, or ‘thinking forms’, in order to reach the judgment, “This is such and such”. These thinking forms exist a priori. There are twelve thinking forms. One of these is causality. Because of this form, we can judge whether or not two successive events have a causal relationship. In an electrical storm, for instance, the sensible qualities are light (from the lightning) and sound (from the thunder). Because we use our causal thinking form, we understand light to be the cause and sound to be the effect.

Besides these thinking forms, we need also forms of intuition: space and time. When we see an object, we always see it through the forms of space and time. It seems, therefore, that all things exist in space and time.

Kant’s attempt at unifying rationalism and empiricism into a new way of understanding cognition was an effort to overcome the then prevailing skepticism and dogmatism in the philosophical world. We have forms of intuition and forms of synthesis inside us congenitally, or a priori; yet the sense-impressions—such as color, shape, aroma—actually come from the outside.

With his transcendental method, Kant tried to make it clear how an experience can become an objective cognition. So, in the Critique of Pure Reason, he maintained that a priori forms are necessary in man’s cognition.

J. Hegel (1770–1831)

-The Idealistic Dialectic

Most idealists begin with God and explain the phenomenal world deductively. Hegel’s theory is deductive, too. Hegel, however, in The Phenomenology of Mind tries to grasp the Absolute epistemologically, starting from sense-consciousness and reaching absolute knowledge, through self-consciousness and reason. Then, he explains deductively how the absolute knowledge, or Logos, develops into the world in the Science of Logic.

Perhaps Hegel questioned why Almighty God created all things, why He did not keep silent eternally. Thus, He developed the concept of Being-Nothing-Becoming. The thinking of God starts from Being, which is pure Being without any determination or feature. Accordingly, Being is at the same time Nothing. For example, we consider that an eraser has weight, shape, and color, but, said Hegel, if we remove its contents we have to say that it merely exists. It exists as indetermination (Bestimmungslosigkeit) and emptiness (Leerheit). This is the same as Nothing. I think that Hegel’s establishment of Being is quite arbitrary.

He explains that, the thesis, Being, and antithesis, Nothing, are in contradiction, and the unity or synthesis of Being and Nothing is Becoming (Dasein). Becoming is the Being which has overcome Nothing. Being becomes Nothing once and then once again becomes Being, only this time it is an enriched Being. The enriched Being then develops into the new dialectical process, Being-Essence-Notion (Idea), which has already been explained in Chapter 5 Logic.

This explanation is very difficult to understand. The reason, I think, is that Hegel did not treat what is true as truth, but wanted to pass something untrue for truth, using complicated logic to do it. Isn’t it enough for us to call an eraser ‘eraser’? The starting point of Hegel’s dialectic is unreliable, so it is natural that it was difficult to develop his logic. It seems somewhat forced.

I will explain his dialectic a little more concretely. The notion (Begriff) develops through the three stages of thesis-antithesis-synthesis. Consider a hen. The notion of ‘hen’ exists in God before the actual hen exists. Next, there appears a notion that denies the hen—the notion of ‘egg.’ Finally, the notion of ‘chicken’ comes to deny egg. The initial notion, therefore, has developed through the three stages of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, or hen, egg, and chicken. Thus, actual hens, eggs, and chickens come to appear.

According to Hegel, nature is what the Idea has developed into in the form of otherness. This is a kind of pantheism, the view that all things are the materialization of the Logos (God) and can be regarded alternately either as God or as matter. Clearly, it is easy to edge into materialism from here; pantheism, therefore, can become the foundation for pan-materialism.

For Hegel, thinking (Logos) develops through the three stages of thesis-antithesis-synthesis, accordingly the phenomenal world develops similarly through the three stages. Therefore, Hegel’s dialectical method is the way of thinking and at the same time the way of development of the world.

K. Marxism

-The Materialistic Dialectic

Marx and Engels constructed the materialistic dialectic by turning Hegel’s idealistic dialectic upside down from the standpoint of materialism. It is the science of nature, human society and thought.1

Although both Hegel’s idealistic and Marx’s materialistic dialectic are those of contradiction—a thing or a state which contains its negation, there is no mention of real struggle in Hegel’s dialectic, in which inseparability and correlativity are stressed, except in an explanatory note2, while the real struggle becomes essential in Marx’s dialectic.

The fundamental laws of the materialistc dialectic, according to Engels are: (1) the law of transformation of quantity into quality, (2) the law of the unity and struggle of opposites and (3) the law of negation of negation.

The first law states that qualitative changes occur only through quantitative changes, and that the quantitative change suddenly brings about a qualitative change at a certain point. The second law states that everything has contradictory elements (opposites), which oppose each other and at the same time cannot be separated from each other, i.e. in the relationship of unity, and that motion and development are caused by the struggle of opposites. The third law states that, in the development of things, the negation of a state leads to a new state and further negation leads to the restoration of the original state, which is not, however, the same as the original state but is the original state in a developed form.

Among these three laws, the most fundamental law of the materialistic dialectic is the law of the unity and struggle of opposites, or the law of contradiction. In fact, Lenin considered it the most fundamental law of the materialistic dialectic. He stated that the unity of opposites is conditional and relative, while their struggle is absolute, and that everything develops through the struggle of opposites. Accordingly, in the final analysis, “the struggle of opposites” is the core of the materialistic dialectic.

L. Husserl (1859–1938)

-The Phenomenological Method

Edmund Husserl said we must understand things as precisely as we do in mathematics. Mathematical precision is the first characteristic of Husserl’s philosophy.

Cognition has three stages. The first is that of seeing things as they are. “To the fact itself” (zu der Sachen selbst) was Husserl’s motto. When we see a flower, we should not think “Oh, this is the beautiful flower I have been dreaming of”. We must take away our subjectivity and see it objectively. In this stage of cognition we see the “fact” (Tatsache), which is purely objective. During this stage we must have a natural attitude (naturliche Einstellung).

A flower, however, is always changing. First it is a bud, then a bloom, and finally it withers and dies. We cannot really say we understand a flower if we do not understand its essence—i.e., what is unchanging in it and what makes it as it is. The change from seeing the actual flower to seeing its essence is called formal reduction (eidetische Reduktion).

The cognition of essence, called ideation (Ideation, Wesensan-schauung), is made by free variation (freie Variation), a process in which the subject freely changes individual beings and finds what is universal in them. The essence of a flower, for example, is obtained, first, by thinking about variety freely (free variation), such as a rose, a tulip, a bud, and a withered flower; then, by taking that which is unchanging and common to all of them.

The final stage of cognition is that which deals with pure phenomena (reines Phanomen). Even if there is a phenomenally existing flower, the essence of it is shaped in our consciousness; we must, therefore, consider consciousness, if we want to have correct cognition.

If we exclude (bracket, einklammern) the actual object and essence of it by the method of suspension of judgment (Epoche), the field of consciousness comes to be the remainder (Residuum). This remainder is called the phenomenological remainder (das phanomenologische Residuum). This is actually pure consciousness (reiner BewuPtsein). Such a procedure is called transcendental reduction (transzendentale Reduktion). The two methods of reduction, formal and transcendental, are together called phenomenological reduction (phanomenologische Reduktion). The attitude of seeing the pure consciousness by phenomenological reduction is called phenomenological attitude (phanomenologische Einstellung).

In the study of consciousness, it becomes clear that consciousness consists of noesis and noema. Noesis is the functional part (thinking part), and noema is the objective part (thought part). True phenomenological cognition is the understanding and cognition of this structure consisting of noesis and noema.

Some people manage to reach the second stage of cognition, but Husserl wants to enter the stage of pure consciousness. He tried to describe man’s consciousness in a strict way. Natural science observes and records facts, trying to eliminate all subjectivity. Ontology considers the essence of the object, and how it exists. The fundamental ontology, which was later developed by Heidegger, however, considers pure consciousness or pure experience.

M. The Analytic Method

Many thinkers have emphasized the study of actual facts in their quest for truth; analytic philosophers, however, tell us that philosophers need not concern themselves with the study of them. Why not? Because we should leave that up to scientists-physicists, biologists, astronomers, botanists, zoologists, and so on; they are the ones who should study actual facts.

Philosophy, science, and all of man’s systems of truth are written in words. First and foremost, therefore, we must study and examine words, to see whether or not they are correctly used. Philosophers have established gigantic philosophical systems; yet, if we analyze the words they used we can find a great number of false expressions. Besides, if we exclude as meaningless that which is not provable or which is ambiguous, a lot of these philosophical systems are doomed to collapse.

Analytic philosophy is positivistic and empirical in every point, largely excluding from its investigation that which man cannot, or does not, experience. So, it considers God as unnecessary for philosophy. Analytic philosophers algebraize words in order to analyze them, since they can acquire mathematical precision by doing so. This, then, is a method for correcting man’s thinking, rather than a method for pursuing truth.

In this section I have outlined the methodologies of representative philosophical systems. Having done this, I would like to introduce Unification Methodology.

II. Unification Methodology

The Give-and-Take Law

Unification Methodology is based on the Unification Principle, and may also be considered as a methodology chat has unified traditional methodologies. The basic law of Unification Methodology is the law of give-and-take action, or briefly, the give-and-take law.

A. Kinds of Give-and-Take Action

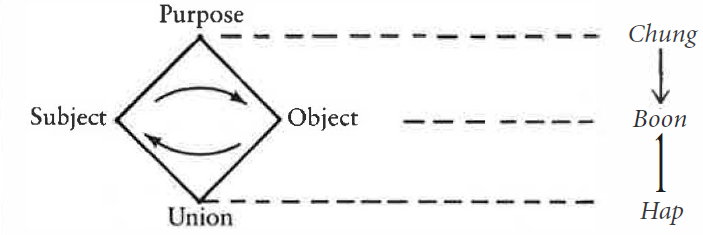

Give-and-take action is the foundation both of the Quadruple Bases and of the Origin-Separation-Union Action or Chung-Boon-Hap (C-B-H) Action. The Quadruple Ba es represent the structure of the attributes of God; the C-B-H action, on the other hand, describes the process of forming the Quadruple Bases from the perspective of time. The Quadruple Ba es consist of Heart (Purpose), Subject, Object, and United Body. When seen from the time perspective, we find that Heart (Purpose) is first; next, Subject and Object conduct give-and-take action; finally, they become one in the United Body. This process is called Chung-Boon-Hap Action. (Fig. 34)

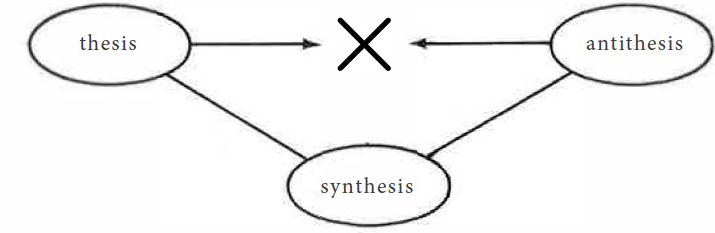

Boon, in the C-B-H action, represents two separate elements in the world of creation relating between themselves as subject and object. These separate elements are not to be understood as divided parts of Chung. Chung, in fact, is purpose established by Heart, and the two elements, centering on Chung, enter into give-and-take action to become Hap (United Body). Of course, God is not a divided being. In God, Boon means not two divided elements, but two relative attributes of the one God. These relative attributes engage in the give-and-take action centering on Chung to become Hap. The meaning of Chung, in the Chung-Boon-Hap of Unification Thought, then, is different from that of ‘thesis,’ in the thesis-antithesis-synthesis of Hegel and Marx.

As explained in “Theory of Original Image,” there are four kinds of Quadruple Bases: Identity-Maintaining, Developing, Inner, and Outer. These derive from the four kinds of give-and-take action—that is, the Identity-Maintaining Give-and-Take Action, the Developing Give-and-Take Action, The Inner Give-and-Take Action, and the Outer Give-and-Take Action.

1. Identity-Maintaining and Developing Give-and-Take Actions

Everything in the natural world has an unchanging, identity-maintaining aspect. Although the universe is always moving and changing, its shape is relatively unchanging. A galaxy revolves, maintaining its shape of a convex lens. Our solar system revolves around the center of our galaxy (a nuclear system of fixed stars), taking two hundred and fifty million years for one revolution; its shape is always elliptical, and it is always at roughly the same distance from the center of the galaxy. Similarly, the nine planets including the earth in our solar system orbit the sun, maintaining their relative positions and shapes.

Nations come and go, since they are not built by God; yet a few of their aspects do not change, even in the non-principled world. The principle of ruling and ruled (in whatever form of national government), is one such example. In the family, the relationship between parents and children has an unchanging, eternal aspect. Every individual has a few characteristics that do not change during his life. In the human body, cells change with body metabolism, yet each part of the body maintains its function and position. With regard to water, whether it be in the form of liquid, steam, or ice, the molecular structure of H20 is unchanging.

The origin of all these identity-maintaining functions is God, the Cause of the phenomenal world for one of God’s attributes is eternity, or unchangeability.

According to the Unification Principle, when a subject and object enter into give-and-take action, all power necessary for its existence, action, and multiplication is generated. Multiplication in the Unification Principle means development and generation; action means movement and change. The multiplication and action of all things are caused by the developing give-and-take actions.

All things develop and change; in the short-term, however, development appears to be a phenomenon characteristic only of living beings. The main factors that initiate development are autonomy and dominion. Autonomy refers to the spontaneity of life, dominion refers to its nature of influencing other beings. Autonomy and dominion are actually different expressions of the function of life; the former applies to the individual truth-body aspect of a living being; the latter, to the connected-body aspect.

In our discussion of development, I will limit my explanation largely to the aspect of autonomy. When a being has autonomy, it develops and grows. Autonomy is an expression of life; it is a kind of latent consciousness, or latent will. From man down to single-celled organisms, all living things have consciousness. God’s Sung Sang can be fully expressed in man’s consciousness, whereas in the consciousness of lower forms of life, only the abilities to grow, to replicate, to respond to stimuli, etc., are expressed. The millions of cells in the body, also, have consciousness (autonomy), and each cell controls itself to a certain extent.

Since autonomy is latent consciousness (or latent will), it has purpose. A living being grows and develops according to this purpose. Development, therefore, has direction. If we sow apple seeds, apple trees will sprout up and eventually bear fruit. The apple seed already has in itself the plan of an apple, and the direction of its growth is to develop into an apple-bearing tree.

Development is the result of the give-and-take action between subject and object in a living being, as for example, between an embryo and albumen in a seed, but in actual fact, not only living beings exhibit the quality of development. The whole universe may be looked upon as a living organism which has developed and expanded over a period of billions of years. The development and expansion of the universe is the process of Creation. As a part of this process, the earth has developed from a gaseous to a molten state, and then to a solid state, with the subsequent appearance of plants, animals, and man.

God’s creation process begins from oneness. All things develop from a simple state to a complex one, from a lower state to a higher one, and from old to new. The complexity of the countless heavenly bodies has arisen from a relatively simple state. Though complex and developed, the heavenly bodies, nevertheless, maintain correlative positions and relationships in the process of expansion; they have developed, keeping their identity.

2. Inner Give-and-Take Action and Outer Give-and-Take Action

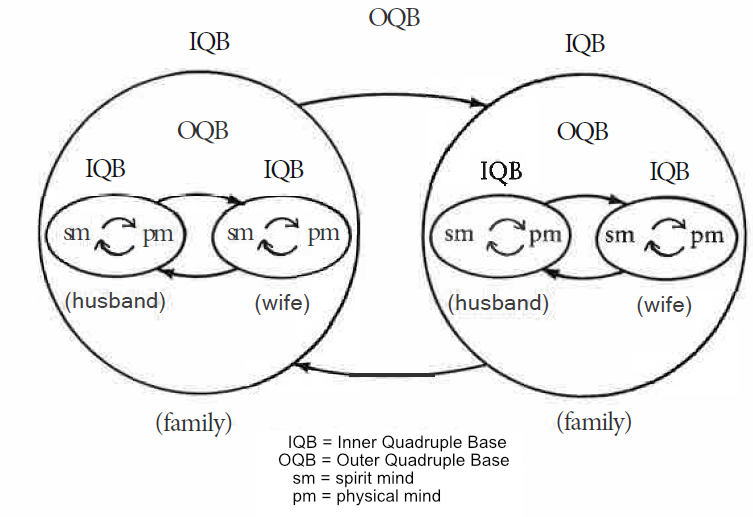

The give-and-take action between a man’s spirit-mind and physical mind is an example of inner give-and-take action, since it makes an inner quadruple base; whereas the give-and-take action between persons (e.g., husband and wife) is outer give-and-take action, since it forms an outer quadruple base. (Fig. 35)

Every existing being engages both in the inner give-and-take action and the outer give-and-take action, but it should be noted that these are relative not absolute concepts. In the Great Macrocosm, there is the spirit-world and the physical world. Relatively speaking, give-and-take action within the physical world can be seen as inner give-and-take action; in this case, the give-and-take action between the physical world and the spirit-world is outer give-and-take action. When considering the solar system in the galaxy, the relationship between the sun and the earth is inner give-and-take action, whereas the relationship between the sun and the galactic center is outer give-and-take action. Furthermore, when considering the earth in the solar system, relationships within the earth are inner give-and-take actions, whereas the relationship between the earth and the sun is outer give-and-take action. This means that inner and outer give-and-take actions are always performed unitively in every stage; in other words, no being exists by itself.

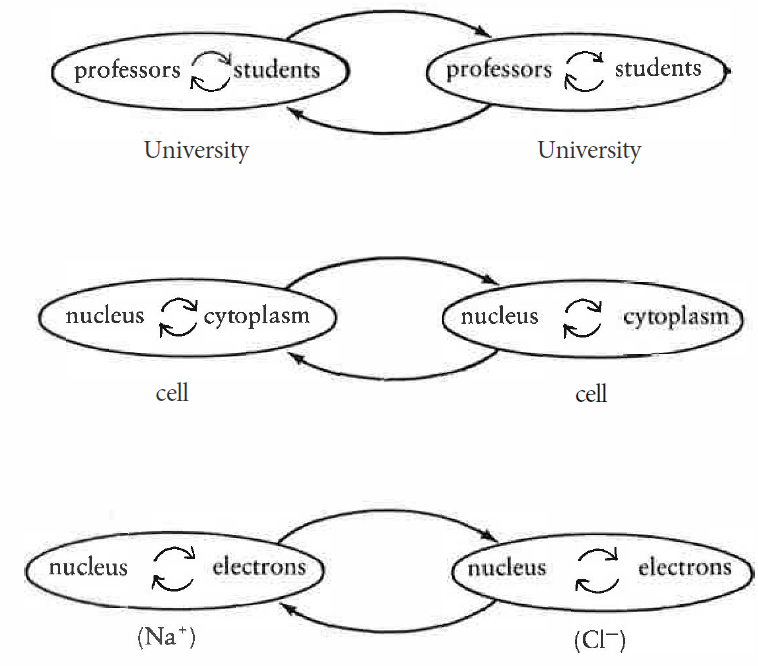

In a nation, the inner give-and-take action between the government (subject) and the people (object) makes the inner quadruple base, whereas the outer give-and-take action between that nation and other nations makes the outer quadruple base. The inner quadruple bases are formed in a university by the inner give-and-take actions between the university president and the professors, between the professors and the students, between faculty members, etc.; at the same time, the university engages in outer, give-and-take action with other universities and organizations, which form outer quadruple bases. The inner give-and-take action between the nucleus and cytoplasm in a cell form an inner quadruple base, and the outer give-and-take actions between that cell and other cells form outer quadruple bases. The same applies for nucleus-electron and atom-atom relationships. (Fig 36)

From the smallest particles to the massive heavenly constellations, all things exist and develop according to inner give-and-take action and outer give-and-take action. If all these relationships are not conducted in a harmonious, principled way, the result will be confusion and ruin.

B. The Sphere of Give-And-Take Action

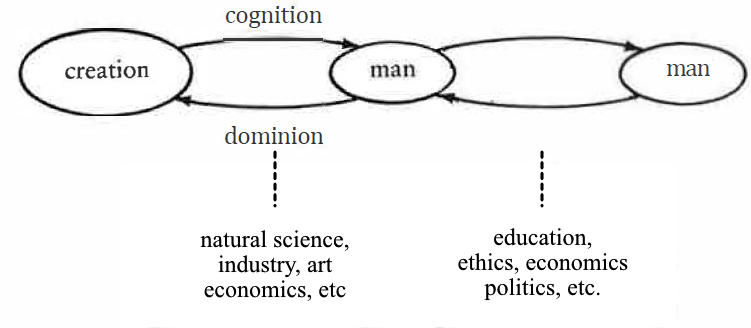

The give-and-take actions thus far discussed are mainly ontological in nature. We should, however, consider other aspects as well, such as the relationships between man and the rest of creation. There are basically two kinds of relationships: in one, man simply recognizes the things to which he relates; in the other, he dominates them as well. The give-and-take action for recognition is epistemological; that for domination is related to such enterprises as natural science, industry, economics, art, and so on.

We should, likewise, consider interpersonal give-and-take actions in the fields of ethics, education, politics, economics, etc. (In economics, which is a field of man’s domination over creation, human relations are of paramount importance.) (Fig. 37)

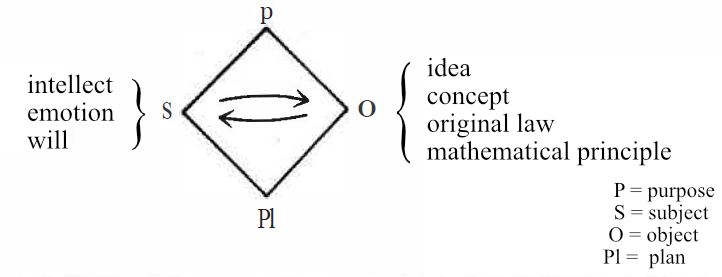

The world of thought, which is related to logic, obeys give-and take laws. The subject (functional) part of the mind consists of intellect, emotion, and will, while the object part consists of ideas, concepts, original law, and mathematical principles. Thinking is achieved by the give-and-take action between the subject and object parts. (Fig. 38)

The concrete contents of the object part are the impressions of what has been experienced. When we want to go on a picnic, we base our thinking on past experiences and may conclude by stating for example, “That’s a good mountain, let’s go there!” Since God is the Creator, He did not need past experiences upon which to base His original thinking; but man does. Man creates new ideas by the combination and synthesis of ideas from past experiences. Ideas from past experiences are gathered and made to enter into give-and-take action with the intellect, emotion, and will, in order to create new plans and ideas.

Judgment, also is based on the give-and-take law. The judgment, “This flower is a rose,” is based on the collative give-and-take action between ‘this flower’ and ‘a rose’, the former being an idea formed from sense-impressions from the outer world, the latter being an idea previously existing in man’s mind. Conversation also, is based on the give-and-take law. If I mumble on randomly, you will not be able to understand what I say. If, however, you can understand what I say, it is because your laws of thinking and my laws of speaking coincide. Truly, all phenomena occur through the give-and-take laws, and we can say that we have a unique and universally true methodology.

C. Types of Give-and-Take Action

1. Bilateral Autonomic Type

You are listening to my lecture now. We are engaged in give-and-take action, with myself in the subject-position and you in the object-position. In this case, both you and I are engaged consciously. The type of give-and-take action in which both the subject and the object are engaged consciously is called bilateral (mutual) autonomic give-and-take action. Other examples are: man as subject and an animal as object, animals as subject and object, etc.

2. Unilateral Autonomic Type

The give-and-take action I am conducting with this piece of chalk in writing on the blackboard is unilateral autonomic give-and-take action, since I am doing so consciously, but the chalk is not. When only one party is engaged consciously, the relationship is called autonomic give-and-take action.

3. Unconscious Type

During the daytime, plants emit oxygen and take in carbon dioxide, while animals always exhale carbon dioxide and inhale oxygen. Plants do not intentionally emit oxygen for the sake of animals—it happens to be a by-product of photosynthesis; neither do animals exhale carbon dioxide to oblige plants—it is a by-product of respiration. By doing so, however, both help each other in what may be termed unconscious give-and-take action. In unconscious give-and-take action, neither the subject nor the object engage consciously, even if both or one of them have consciousness (autonomy).

4. Heteronomous Type

When both subject and object are inanimate beings and they are engaged in give-and-take action by the will of an outside agency, this type of give-and-take action is called heteronomous give-and-take action. The earth and the sun are engaged in give-and-take action in the solar system, since they are forced to do so by God. The parts of a clock are engaged in give-and-take actions in such a way as to tell time, since they are forced to do so by the will of man who made it. These are examples of heteronomous give-and-take actions.

5. Contrast Type (Collation Type)

When man contrasts or collates two or more beings (elements) and he finds harmony in them, he considers that they are engaged in give-and-take action, which may be called contrast type (collation type) give-and-take action. In many cases, the contrast is performed unconsciously. We feel harmony and beauty when we see mountains, the sea, clouds, and flying birds, or we see a house with a red roof in the middle of a green forest. These feelings of harmony come from the contrast type of give-and-take action. In this give-and-take action, what generally happens is that man unconsciously places one of the things in the subject position, and the others in the object position; their being engaged by an observer means that the give-and-take action is of the contrast type.

This type of give-and-take action is often applied intentionally, in order for man to obtain joy. Art is a good example. Artists apply it to arranging colors, light and shadow, lines, concave and convex parts, and so on, in order to produce a harmonious work of art.

Even in logic, thinking is formed through this type of give-and-take action. For instance, the proposition, “This flower is a rose,” is formed by a process of give-and-take action. ‘This flower’ is subject; ‘a rose’ is object; and ‘is’, which is a logical term, is the contrasting, or judging element of the action. In cognition, we collate the sense-impressions of the object we see—that is, shape, color, aroma, etc.—with the corresponding prototypes we have inside us.

By the way, it must be noted that a contrast type give-and-take action is always accompanied by a unilateral autonomic type give-and-take action between man, who contrasts, and things, which are contrasted with each other.

D. Characteristics of Give-and-Take Action

The characteristics of give-and-take action are as follows: (1) correlative elements (paired elements); (2) purpose and centrality; (3) order and locality; (4) harmony; (5) individuality and relationship; (6) identity-maintenance and development; (7) circular motion (in space and time). These have already been explained as the Seven Natures of Cosmic Law, in “Ontology.”

III. A Critique of Traditional Methodologies Viewed from Unification Methodology

The purpose of this critique is to provide additional clarification of Unification Methodology.

A. Heraclitus

Heraclitus, in saying that all things in the universe are changing and growing, considered only the equivalent of the developing give-and-take action in Unification Methodology. He neglected the identity-maintaining aspect.

B. Zeno

Zeno tried to prove that everything is unchangeable, immovable, immortal, and not-born. Contrary to Heraclitus, Zeno was concerned only with the identity-maintaining aspect, and he neglected the developing aspect.

C. Socrates

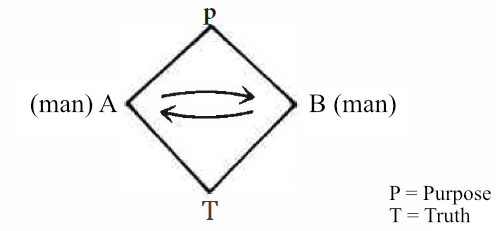

A and B initiate a dialogue in order to arrive at truth. This is outer give-and-take action between A and B centering on the purpose of finding truth, and their multiplying new truth is the outer developing quadruple base. Socrates’ dialogic method, then, demonstrates the outer developing give-and-take action in Unification Methodology. (Fig. 39)

D. Plato

Plato studied the world of Idea. He can be said to have studied, unintentionally, the world of the Inner Hyung Sang of God. There are numerous ideas and concepts in the Inner Hyung Sang. Plato classified these, making a hierarchy of Ideas. Classifying them involves a collative give-and-take action. For example, collating the concept of ‘animal’ with the concept of ‘horse’, we conclude that the concept of ‘animal’ is generic, while the concept of ‘horse’ is specific. All this is collation type and inner give-and-take action.

E. Aristotle

Aristotle’s deductive method employs syllogisms, in which a universal truth is stated, then a more limited truth, and from these a conclusion is finally obtained. The conclusion (C) ‘Socrates will die’ is obtained by collating the two propositions: (A) ‘All men die’ (major premise) and (B) ‘Socrates is a man’ (minor premise). This inference is a collation type give-and-take action. Moreover, the proposition, ‘Socrates is a man’, is itself obtained by comparing ‘Socrates’ and ‘a man’; i.e. by a collation type give-and-take action. Aristotle’s deductive method, therefore, is an expression of the collation type and inner give-and-take action. The collation type completing quadruple bases, which I have explained in Chap. 5 Logic, are formed through this give-and-take action, both in making a conclusion in the syllogism and in establishing each proposition.

F. Bacon

Bacon maintained that we must free ourselves from our prejudices (idola) and make careful experiments. and observations in order to arrive at the truth. Suppose the results of observations A, B, and C are all P. We can then make a general law, with P as the conclusion. For example, Mr. A dies, and so do Mr. B and Mr. C. We can then make the general law, ‘All men die’. This is the inductive method. The inductive method, therefore, involves contrast-type give-and-take action.

The inductive method is based on experiments and observations which involve outer give-and-take actions. Also, it involves collation type give-and-take action, since a conclusion is drawn by comparing various observations. We see, therefore, that Bacon emphasized outer give-and-take action and collation type give-and-take action.

G. Descartes

Descartes doubted the existence of all things; he doubted the real existence of mountains, of rivers, even of his own body. Then he arrived at the famous proposition, “I think, therefore I am”. For him, this proposition is the only believable truth. From the viewpoint of Unification Thought, the setting up of his proposition is the equivalent of his recognition of the inner quadruple base both in God and in man. But how was Descartes able to arrive at that proposition? Doubting all matter (Hyung Sang) means denying God’s creation of the world. Then, what is left? It can be nothing other than God’s thinking before beginning Creation. Descartes can be said to have unconsciously dealt with God’s thinking, which, is actually His Sung Sang (Inner Quadruple Base).

H. Hume

The relationship of cause and effect is not purely subjective—as Hume maintained—but is both subjective and objective, as explained in Epistemology. (See ch. 4, I, B, 2.) Besides denying the existence of the material substance, Hume denied also the substantial reality of the self, saying that the self is nothing but a bundle of perceptions (impressions and ideas). He considered a bundle of perceptions the only believable existence. In Unification Thought terminology, Hume limited himself to the study of the Inner Hyung Sang, which contains perceptions.

I. Kant

According to Unification Principle, man is the integration, or encapsulation, of the universe; thus, he possesses all the elements of the outside world representationally as prototypes inside himself. As explained in the previous section, one of the characteristics for give-and-take action is correlativity. Cognition cannot be achieved with an outer element only. Both inner and outer elements must be related.

The inner element may seem to be transcendental, and Kant was convinced that it is, but actually it is not. A newborn baby, as he has only an incomplete prototype, does not understand anything clearly. His prototype is gradually completed with his growth. What he has experienced is included in his prototype, and the new prototype becomes the standard of cognition for the next experience. The prototype in Unification Thought, therefore, has both a transcendental and an empirical element. (We call this concept priority of the prototype, as explained in Epistemology.)

Both Kant and Unification Thought are in accord in considering that cognition is accomplished through the reciprocal relationship between outer and inner elements. For Kant, what comes in from the outside are sensible qualities, such as color, shape, aroma, etc., and what is in the inside are the forms of intuition and the forms of synthesis. The object of cognition is synthesized by these a priori forms inside.

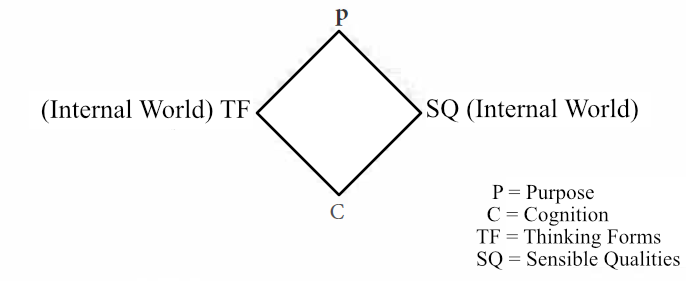

According to Unification Thought, however, what is inside are content (image of content) as well as thinking forms—prototypes consist of both of them—and what is outside are sensible qualities (content) with existing forms. For Kant, the object of cognition is synthesized by the subject. In Unification Thought, however, subject and object are collated in cognition. Kant’s transcendental method (theory of synthesis) can be said to be Kant’s style of manifesting the theory of collation, which is established on the basis of the give-and-take action theory. (Fig. 40)

J. Hegel

Instead of explaining the development of thinking and that of the universe as the process of Chung-Boon-Hap, Hegel explained it as the process of thesis-antithesis-synthesis. Also, he thought that God is Logos. Logos, however, is not God Himself, but the multiplied being of the give-and-take action between Inner Sung Sang and Inner Hyung Sang in God. Logos is the product of the Inner Developing Quadruple Base, which performs give-and-take action with the Hyung Sang, centering on Purpose, to create existing beings.

Hegel had no concept of Quadruple Base, but thought that the universe had developed directly from the Logos. Accordingly he had to create an antithesis (Nothing) to explain this development. He regarded the relationship between thesis and antithesis as one of contradiction, and thought that new things were born as the synthesis of the interaction between these contradictory elements. This can be said to be his style of understanding the manifestation of give-and-take action between correlative elements, but they are quite different. He did not know that the development is brought about by the give-and-take action centering on purpose, that is, by the formation of a quadruple base. (Fig. 41)

K. Marxism

The fault of the most fundamental law of the materialistic dialectic, the law of the struggle of opposites (the law of contradiction), has already been mentioned in Chapter 2 Ontology. In the Unification Thought view, development is made not through contradiction, that is, through the struggle of opposites, but through the harmonious give-and-take action of the correlative elements in nature, society and thinking.

With regard to the law of the transformation of quantity into quality, Unification Thought asserts that quality (Sung Sang) and quantity (Hyung Sang) are relative aspects of an existing being, so quality and quantity develop simultaneously. In the Unification Thought view, quality is expressed through quantity since quality and quantity are in the relationship of subject and object, contrary to the materialistic dialectical view that quantitative change is the cause with qualitative change as the effect. Also, Unification Thought asserts that a sudden change of quality is not a general phenomenon, but a gradual change of quality is a general one.

With regard to the law of negation of negation, which claims that a new state is attained by the negation of an old one, Unification Thought asserts that the new state is attained affirmatively from an old one through the give-and-take action of the correlative elements in it. Materialistic dialectic claims that the original state is restored in a more developed form through the negation of negation without any reason. Unification Thought, however, clarifies that such a restoring phenomenon appears through circular motion in time (spiral movement), one of the characteristics of the give-and-take law, by which every living being maintains its eternity. Clearly, such a phenomenon cannot be applied to the social revolution as Marx claimed.

L. Husserl

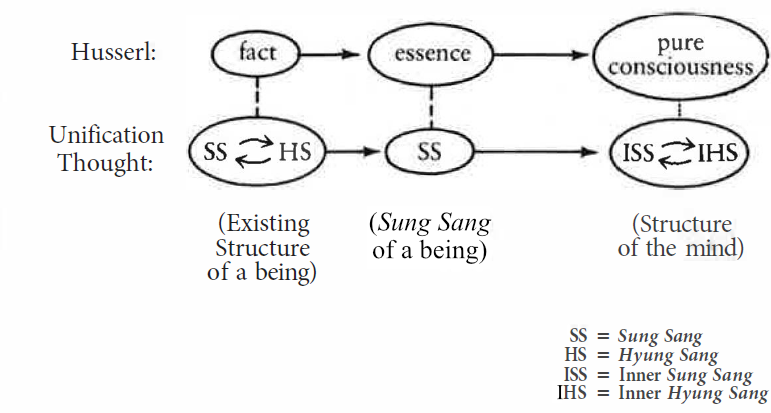

Husserl describes three stages of cognition: the cognition of reality (the fact, without the perceiver’s subjectivity), the cognition of essence, and the cognition of pure phenomena.

The realm of the ‘fact itself’ (Sachen selbst) is the realm of scientific cognition. In Unification Thought, this is the cognition of the united body of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang of the existing being. (Most scientists, however, study only the Hyung Sang aspect.) Essence in the second stage corresponds to the Sung Sang of that being. Husserl asks us to suspend our judgments of the outside world (phenomenological epoche) in order to analyze pure consciousness. Having done this, we can understand that pure consciousness consists of a thinking part and a thought part-that is, a functional part and an objective part. This is no more than the equivalent of the Inner Sung Sang and Inner Hyung Sang of man’s mind in Unification Thought. (Fig. 42)

M. The Analytic Method

Analytic philosophers are concerned only with the mathematical accuracy and logical consistency of a system of thought. Their analytic process is carried out through an intellectual inner give-and-take action. We have seen in the chapter on logic, (see Ch. 5, III, B) however, that inner give-and-take action includes both an intellectual aspect (logos) and an emotional aspect (pathos). We can say, therefore, that the analytic method deals only with one aspect of the inner give-and-take action.