| When's the last time you went to church? The chances are that, because

this is a men's issues newsletter, it's been quite a while, if at all. If you did go, the

chances also are that you and the other men were in the minority. ARMIES

OF WOMEN

Fact is, most

Christian churches in the West have high female majorities. It's been that way for a long

time. That's the message in Leon Podles' The Church Impotent, The Feminization of

Christianity. (Dallas, TX: Spence Publishing Co. 1999.) His first chapter,

"Armies of Women," starts with this statement: "Despite the constant

complaints of feminists about the patriarchal tendencies of Christianity, men are largely

absent from the Christian churches of the modern Western world. Women go to church; men go

to football games." He then declares, "Men say they believe in God about as

often as women do, but they attend church much less frequently than women, and they engage

in private religious activities far less often ... The clergy have long had the reputation

of not being very masculine" which is another reason why men tend to stay away. To

most men, religion is a gal thing. Fact is, most

Christian churches in the West have high female majorities. It's been that way for a long

time. That's the message in Leon Podles' The Church Impotent, The Feminization of

Christianity. (Dallas, TX: Spence Publishing Co. 1999.) His first chapter,

"Armies of Women," starts with this statement: "Despite the constant

complaints of feminists about the patriarchal tendencies of Christianity, men are largely

absent from the Christian churches of the modern Western world. Women go to church; men go

to football games." He then declares, "Men say they believe in God about as

often as women do, but they attend church much less frequently than women, and they engage

in private religious activities far less often ... The clergy have long had the reputation

of not being very masculine" which is another reason why men tend to stay away. To

most men, religion is a gal thing.

It wasn't always that way. Podles tells how it once was and might be again, and in

the telling he provides still another way of recovering the past, rescuing the truth about

our pre-1970 lives from the feminist mythology that now obscures it. One of the myths has

been that the big Christian churches, particularly the Roman Catholic Church, are bastions

of patriarchy. The truth is that the RCC in particular has been increasingly feminized

since the early middle ages, one reason for the Protestant Reformation.

The RCC has an all-male clergy, for which it is constantly damned, and still asks

her (that's right, we speak of the RCC as a "she") faithful to pray to a God the

Father and His Son, Jesus. But, as Podles points out, a large number of the male clergy

rank low in the masculinity scale, and they have supported a strong feminist movement

within the Church which has relentlessly pushed for an "inclusive" clergy and

gender neutral language for the deity. They are thus further feminizing a Church that has

suffered feminization for almost a millennium, and, if not stopped, will turn it into a

goddess cult.

In his discussion

of Judeo-Christianity's origins, Podles exposes another feminist myth: that "the

patriarchy" began as a monster system to oppress women. It began instead, he reports,

as a masculine ideology into which males were initiated, part of a process found in nearly

every society. Men are born male but become masculine only by separating themselves from

(the) feminine in which they have been immersed during their early lives and then

immersing themselves in masculine communities. There is a temporary period of misogyny

during which the male tries to distance himself from whatever looks or sounds feminine, in

particular the primarily female drive toward intimacy and communion. In his discussion

of Judeo-Christianity's origins, Podles exposes another feminist myth: that "the

patriarchy" began as a monster system to oppress women. It began instead, he reports,

as a masculine ideology into which males were initiated, part of a process found in nearly

every society. Men are born male but become masculine only by separating themselves from

(the) feminine in which they have been immersed during their early lives and then

immersing themselves in masculine communities. There is a temporary period of misogyny

during which the male tries to distance himself from whatever looks or sounds feminine, in

particular the primarily female drive toward intimacy and communion.

Masculinity separates. Femininity unites. And for a while, the male must separate

from the feminine in order to achieve an identity which will enable him to re-unite with

the feminine, not as oppressor but as lover, protector, and provider. Masculinity is an

ideology of sacrifice and service: duty ... honor ... country.

As Podles puts it, a man "must give up being mothered before he can become a

father. He must reject the feminine in himself, cultivating a  distance from the world of women, so that he can one day return to it, not as

a recipient but as a giver. To be masculine, a man must be willing to fight and inflict

pain, but also to suffer and endure pain. He seeks out dangers and tests of his courage

and wears the scars of his adventures proudly. He does this not for his own sake, but for

the community's, to protect it from its enemies, both human and (otherwise). Masculine

self-affirmation is, paradoxically, a kind of self-abnegation. A man must always be ready

to give up his life [and accept the knowledge of his expendability.] A woman faces danger

in childbirth, a risk that she cannot (in pre-contraceptive societies) escape. A man has

to accept danger freely and willingly, or else he is not masculine. Men nurture their

society by shedding their blood, their sweat, and their semen, by bringing home food for

both child and mother, and by dying if necessary in faraway places to provide a safe haven

for their people." Masculinity is not a natural endowment. It is a difficult

achievement. distance from the world of women, so that he can one day return to it, not as

a recipient but as a giver. To be masculine, a man must be willing to fight and inflict

pain, but also to suffer and endure pain. He seeks out dangers and tests of his courage

and wears the scars of his adventures proudly. He does this not for his own sake, but for

the community's, to protect it from its enemies, both human and (otherwise). Masculine

self-affirmation is, paradoxically, a kind of self-abnegation. A man must always be ready

to give up his life [and accept the knowledge of his expendability.] A woman faces danger

in childbirth, a risk that she cannot (in pre-contraceptive societies) escape. A man has

to accept danger freely and willingly, or else he is not masculine. Men nurture their

society by shedding their blood, their sweat, and their semen, by bringing home food for

both child and mother, and by dying if necessary in faraway places to provide a safe haven

for their people." Masculinity is not a natural endowment. It is a difficult

achievement.

It is these same dynamics which makes God masculine. As feminists perpetually

deplore, the God of Judeo-Christianity is masculine, a He who has a Son. He is not male.

God is spirit, neither male nor female ... but, Podles emphasizes, He is necessarily

masculine, for two reasons. "He transcends creation: it is not part of him, nor did

it come out of him — he spoke, and it was. God is therefore, utterly separate from

creation, that is, he is holy. To be holy is to be separated, set apart from common or  profane use ... Though God transcends his

creation, he loves it, and is involved in it. A transcendent God is a masculine God, a

feminine or bisexual God is an immanent God, one who is part of creation or the creation

is part of him-her. profane use ... Though God transcends his

creation, he loves it, and is involved in it. A transcendent God is a masculine God, a

feminine or bisexual God is an immanent God, one who is part of creation or the creation

is part of him-her.

Such a concept of the deity is more than a matter of religious preference, as good

as any other. It is for example the precondition for science. Some today are in the habit

of seeing religion and science as antagonistic, but the monotheistic masculine God of

Judeo-Christianity is actually the precondition from which science can emerge. It is

because of its fundamental separations: creator from creation, observer from object, law

giver from laws. There is, in the concept of such a deity, the presumption of a single

source of order and unity in the cosmos.

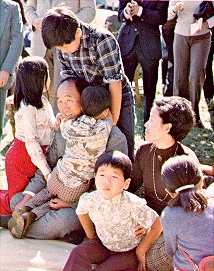

It is also the precondition for patriarchy, a system that disciplines men for

fatherhood, which is a man's way of imitating God. "Patriarchy," Podles writes,

"is not simply an affirmation of masculinity; it is not 'a synonym for male dominance

or for a system in which male traits are valued over female ones.' Still less is it simply

a synonym for exploitation and domination, though that is the current feminist usage.

Patriarchy is a system in which fathers care for their families and find their emotional

centers in their offspring. In ancient Israel, the image of father was not primarily one

of authority and power, but one of adoptive love, covenant bonding, tenderness, and

compassion. Patriarchy, we can easily forget,  was and is a great achievement in the face of the male tendency

to promiscuity and alienation from children and the women who bear them. It is ... one of

the greatest achievements of any religion." was and is a great achievement in the face of the male tendency

to promiscuity and alienation from children and the women who bear them. It is ... one of

the greatest achievements of any religion."

Patriarchy has its risks and inner tensions among which is the female disinclination

toward separation and objectivity and rationality. In its first thousand years

Christianity, like the Judaism out of which it emerged, was strongly masculine and, by the

middle ages it was becoming, with its scholastic theology, hyper-rational, at least as the

female faithful saw it. There then began those developments which set Christianity toward

the widespread feminization that threatens it today. One was a subtle shift in the

mystical belief in brideship. The Church was understood as the bride of Christ, that is

the entire Church as a community. But in the early middle ages the belief was altered to

mean that each individual was Christ's bride ... passive, obedient, receptive ... and that

was a role which men in increasing numbers felt uncomfortable with. In addition there was

something of a feminist movement at the time, the "Frauenbewegung" which brought

more women into religious orders. And more women meant increasing trends toward mysticism,

which emphasizes the emotional bonding with God.

Such developments led to near heretical beliefs which deeply concerned the Church

fathers and, in the long run, contributed to the female moral vanity which has blossomed

in feminist ideology. One was Quietism, which declared that "man's highest perfection

consists in a sort of psychical self-annihilation and a subsequent absorption of the soul

in the Divine Essence. From this comes

Illuminism, the doctrine that the perfected soul, since it is God, or so closely united

with him as to be indistinguishable from him, cannot sin. From this comes

Illuminism, the doctrine that the perfected soul, since it is God, or so closely united

with him as to be indistinguishable from him, cannot sin.

It is easy to see in this belief the origin of the feminist belief that a woman can

do no wrong. You see it most prominently displayed in the concept of "choice" as

it applies to aborting a child or setting up a fatherless family. Such choices are morally

right not because they correspond to a universal law but because they correspond to a

woman's personal assessment of her needs. It is "right for her" and therefore it

is right. (My emphasis. RFD)

This self-referencing morality and gender egotism — which feminism has been

preaching to a widespread female congregation, was already manifest in 19th Century

America, helped along by a largely feminized clergy. "By the nineteenth

century," writes Podles, "the home, mother, and God were joined in a Victorian

Trinity, and Heaven was the restoration of the family circle beyond the grave: Women,

confined to the home, already lived half in heaven ..." Throughout that century

ministers and women worked together against men, especially young men; 'It was  often as a covert crusade to salvage not

the alcoholic but the woman at his mercy. The drunkard, usually a male, destroys by his

debaucheries himself and his saintly wife, mother, daughter, or sister who loves him and

would draw him from the saloon to the fireside; Women took over the leadership of family

prayers; men were obviously unsuitable." often as a covert crusade to salvage not

the alcoholic but the woman at his mercy. The drunkard, usually a male, destroys by his

debaucheries himself and his saintly wife, mother, daughter, or sister who loves him and

would draw him from the saloon to the fireside; Women took over the leadership of family

prayers; men were obviously unsuitable."

One wonders if all this stomach turning sentimentality and woman worship was what

was driving men to drink in the first place.

Podles describes the masculinity at the heart of Judeo-Christian patriarchy as a

"natural ideology." That is, it is natural for men to seek masculinity. Boys

want to separate from the feminine and become men, and they will enter societies that

helps them with that effort. But not all masculine societies will turn boys into men and

men into fathers who will return to women as lovers and protectors. Masculinity has a

propensity toward fascism as happened in that hyper-masculine cult that Hitler organized.

It is also happening in street gangs, where boys go to find a masculinity denied them in

our increasingly male-hostile society.

All of this

suggests still another variation of Churchill's dictum: that Judeo-Christian patriarchy is

the worst of all the masculine societies , except for all the others. All of this

suggests still another variation of Churchill's dictum: that Judeo-Christian patriarchy is

the worst of all the masculine societies , except for all the others.

Which is also another reason to worry about feminism and feminization, because, for

the last thirty years feminists have busily trashed Judeo-Christian masculinity. It is for

them the Satan System which oppresses women. They believe that on its ruins they can build

a non-masculine society that will produce males who are nicer to women.

They're in for a colossal disappointment, which many of them are already

experiencing. Because if they didn't like the kind of men traditional society was

producing in the twentieth century, they are going to like even less the kind of men a

feminized society will produce in the twenty-first century.

|

It is a

straightforward fact that half of the human population is born male. Being a male and

becoming a man, however, are two different things. To become a man, a boy has to undergo a

process that is often stormy and perilous.

It is a

straightforward fact that half of the human population is born male. Being a male and

becoming a man, however, are two different things. To become a man, a boy has to undergo a

process that is often stormy and perilous. Boys who are growing into men need

guidance. If a boy tries to become a man on his own, he will probably fail, and in any

society where a significant number of men never grow up, there will be suffering. For

unmanly men tend to two extremes: either soft and selfish, unwilling to support or defend

others, or harsh and violent, accustomed to brutally taking whatever they want.

Boys who are growing into men need

guidance. If a boy tries to become a man on his own, he will probably fail, and in any

society where a significant number of men never grow up, there will be suffering. For

unmanly men tend to two extremes: either soft and selfish, unwilling to support or defend

others, or harsh and violent, accustomed to brutally taking whatever they want. Wherever they do remain, masculine

traditions are derided as irrational. Of course they are irrational. But manhood is not

rational. It is not rational to die to protect others. Manhood is a cultural invention

that is practical (indeed, vital) for society. But it is not built on individual reason.

Wherever they do remain, masculine

traditions are derided as irrational. Of course they are irrational. But manhood is not

rational. It is not rational to die to protect others. Manhood is a cultural invention

that is practical (indeed, vital) for society. But it is not built on individual reason. It is very, very

easy for a boy unguided by the inheritance of the traditional male script to go wrong.

Critics who attack "patriarchy" and the teaching rituals of masculinity are

wrong if they think the result will be a gentler, more androgynous society. It will be

gangsta rappers and — beyond them, when the chaos becomes intolerable — the dark

shadows of nihilism and the black uniforms of the S.S.

It is very, very

easy for a boy unguided by the inheritance of the traditional male script to go wrong.

Critics who attack "patriarchy" and the teaching rituals of masculinity are

wrong if they think the result will be a gentler, more androgynous society. It will be

gangsta rappers and — beyond them, when the chaos becomes intolerable — the dark

shadows of nihilism and the black uniforms of the S.S. In his discussion

of Judeo-Christianity's origins, Podles exposes another feminist myth: that "the

patriarchy" began as a monster system to oppress women. It began instead, he reports,

as a masculine ideology into which males were initiated, part of a process found in nearly

every society. Men are born male but become masculine only by separating themselves from

(the) feminine in which they have been immersed during their early lives and then

immersing themselves in masculine communities. There is a temporary period of misogyny

during which the male tries to distance himself from whatever looks or sounds feminine, in

particular the primarily female drive toward intimacy and communion.

In his discussion

of Judeo-Christianity's origins, Podles exposes another feminist myth: that "the

patriarchy" began as a monster system to oppress women. It began instead, he reports,

as a masculine ideology into which males were initiated, part of a process found in nearly

every society. Men are born male but become masculine only by separating themselves from

(the) feminine in which they have been immersed during their early lives and then

immersing themselves in masculine communities. There is a temporary period of misogyny

during which the male tries to distance himself from whatever looks or sounds feminine, in

particular the primarily female drive toward intimacy and communion. distance from the world of women, so that he can one day return to it, not as

a recipient but as a giver. To be masculine, a man must be willing to fight and inflict

pain, but also to suffer and endure pain. He seeks out dangers and tests of his courage

and wears the scars of his adventures proudly. He does this not for his own sake, but for

the community's, to protect it from its enemies, both human and (otherwise). Masculine

self-affirmation is, paradoxically, a kind of self-abnegation. A man must always be ready

to give up his life [and accept the knowledge of his expendability.] A woman faces danger

in childbirth, a risk that she cannot (in pre-contraceptive societies) escape. A man has

to accept danger freely and willingly, or else he is not masculine. Men nurture their

society by shedding their blood, their sweat, and their semen, by bringing home food for

both child and mother, and by dying if necessary in faraway places to provide a safe haven

for their people." Masculinity is not a natural endowment. It is a difficult

achievement.

distance from the world of women, so that he can one day return to it, not as

a recipient but as a giver. To be masculine, a man must be willing to fight and inflict

pain, but also to suffer and endure pain. He seeks out dangers and tests of his courage

and wears the scars of his adventures proudly. He does this not for his own sake, but for

the community's, to protect it from its enemies, both human and (otherwise). Masculine

self-affirmation is, paradoxically, a kind of self-abnegation. A man must always be ready

to give up his life [and accept the knowledge of his expendability.] A woman faces danger

in childbirth, a risk that she cannot (in pre-contraceptive societies) escape. A man has

to accept danger freely and willingly, or else he is not masculine. Men nurture their

society by shedding their blood, their sweat, and their semen, by bringing home food for

both child and mother, and by dying if necessary in faraway places to provide a safe haven

for their people." Masculinity is not a natural endowment. It is a difficult

achievement. profane use ... Though God transcends his

creation, he loves it, and is involved in it. A transcendent God is a masculine God, a

feminine or bisexual God is an immanent God, one who is part of creation or the creation

is part of him-her.

profane use ... Though God transcends his

creation, he loves it, and is involved in it. A transcendent God is a masculine God, a

feminine or bisexual God is an immanent God, one who is part of creation or the creation

is part of him-her. was and is a great achievement in the face of the male tendency

to promiscuity and alienation from children and the women who bear them. It is ... one of

the greatest achievements of any religion."

was and is a great achievement in the face of the male tendency

to promiscuity and alienation from children and the women who bear them. It is ... one of

the greatest achievements of any religion." From this comes

Illuminism, the doctrine that the perfected soul, since it is God, or so closely united

with him as to be indistinguishable from him, cannot sin.

From this comes

Illuminism, the doctrine that the perfected soul, since it is God, or so closely united

with him as to be indistinguishable from him, cannot sin. often as a covert crusade to salvage not

the alcoholic but the woman at his mercy. The drunkard, usually a male, destroys by his

debaucheries himself and his saintly wife, mother, daughter, or sister who loves him and

would draw him from the saloon to the fireside; Women took over the leadership of family

prayers; men were obviously unsuitable."

often as a covert crusade to salvage not

the alcoholic but the woman at his mercy. The drunkard, usually a male, destroys by his

debaucheries himself and his saintly wife, mother, daughter, or sister who loves him and

would draw him from the saloon to the fireside; Women took over the leadership of family

prayers; men were obviously unsuitable." All of this

suggests still another variation of Churchill's dictum: that Judeo-Christian patriarchy is

the worst of all the masculine societies , except for all the others.

All of this

suggests still another variation of Churchill's dictum: that Judeo-Christian patriarchy is

the worst of all the masculine societies , except for all the others. In the book Defending

the Family: A Sourcebook edited by Paul C. Vitz and Stephen M. Krason Leon is an

"anthology critiquing contemporary anti-family trends and provideing a scholarly

defense of the family. One article is by Leon Podles titled "The Destiny of Men: Patriarchy or

Crime." We haven't read this article but the title makes

it clear that where there is no patriarchy and especially where there is matriarchy like

in the slums there is more crime than there is where there is strong male leadership.

In the book Defending

the Family: A Sourcebook edited by Paul C. Vitz and Stephen M. Krason Leon is an

"anthology critiquing contemporary anti-family trends and provideing a scholarly

defense of the family. One article is by Leon Podles titled "The Destiny of Men: Patriarchy or

Crime." We haven't read this article but the title makes

it clear that where there is no patriarchy and especially where there is matriarchy like

in the slums there is more crime than there is where there is strong male leadership.