![]()

The Words of the Bowles Family

|

|

The Words of the Bowles Family |

Claire Bowles was one of the original foreign missionaries of 1975 before joining her husband in Thailand.

I had been trying for months to get a "camp pass" from the government, which would enable me to visit the Vietnamese refugee camp of Sikieu where International Relief Friendship Foundation (IRFF) of Japan has a medical team working. Finally, it was arranged and I went to see the camp. I had already been to several refugee camps with my journalist husband, so I was prepared for what I would see there. We had gone to both Laos and Cambodia border camps. We even went inside Cambodia and visited camps in the "liberated zone."

That is the kilometers of land that the resistance army liberated from the communists. There is a constant tugging back and forth for those few miles; the resistance takes it and the communists take it back again (aided by the Soviets, of course) and so on. We had met Laotian, hill tribe, and Cambodian refugees, talked with them, interviewed them, laughed with them, felt for them. But I had never met Vietnamese refugees or been to a Vietnamese camp.

I arrived at the Sikieu camp in the morning and the IRFF workers were already busy. The hospital was crowded with patients waiting to see the doctors and pick up the prescriptions. I made a big splash, being the only blonde among thousands; all the IRFF workers are Japanese, so many of the children had never seen light hair before. There were many big, dark eyes on me as I made my greetings to the team. I had met them all in Bangkok so no introductions were necessary, except for the Vietnamese medical workers who had backgrounds in medicine back at home and, after escaping the communist regime of Vietnam, volunteered to help at the hospital in the camp. These were very strong, capable people who wanted to help their people while waiting for their future to be decided by governments such as America, France or Canada.

All refugees were waiting for resettlement in a third country, and those governments can accept and reject whom they wish. Everyone we met told proudly of his brother in Canada, his sister in Oregon or Ohio, or his niece in France. These will be accepted by any country, most likely.

As my tour of the camp began, I quickly acquired several volunteers to guide me around. These young men were from the seminary run in the camp by a Catholic mission. They all looked much younger than their age. All of them had been in Communist "re-education" camps back in Vietnam for more than five years. They laughed when they called them "reeducation" camps because, my guides told me, they are really prisons and there is no education involved except hard work. Most of the people in these prisons were connected with the American army in some way and posed a threat to the communist government. I learned that all three of my guides had been to America during the Vietnam War to train in the military. Two had been helicopter pilots and one was an explosives expert. They told of their escape from Vietnam after being released from prison. One man had set sail at night in a small boat with 38 people. They were attacked by pirates who wanted their boat. The pirates threw everybody overboard and took the boat... 25 people died. The strong ones swam. "I swam 5 hours. I was surprised that I made it." He laughed.

They took them to the "Minors' Center" which is an orphanage for the children whose parents are either dead or still in Vietnam. Many families pay large sums of money to have their child accompany a group of boat people, even though they are often strangers and the future of their child is extremely questionable. Somehow, they find this better than life in Vietnam. The child is given over to the "Unaccompanied Minors" official upon arrival at their camp. Sikieu has over 200 of these kids, some of them only three years old. They have a large, bamboo building, lots of bamboo beds (no mattresses or pillows) and blankets, because it is sometimes very cold in Thailand. Fifteen Vietnamese volunteers help out at the minors' center, taking care of the children, cooking, counseling, trying to arrange American sponsors by helping with all the paperwork.

I toured the living areas next where the 7000 refugees live and do their chores. They have no privacy, no luxuries, and very little water. (Only one bucket per person per day). Many receive money from their relatives in America or France, but there is little to buy besides soap and extra food.

Back at the hospital I toured all of its seven rooms. Each room is double-purposed. One is office/pharmacy, another is laboratory/pediatrics, another is minor surgery/obstetrics, etc. I spent several hours watching in the various rooms as patients came in with wounds to be cleaned, illnesses to be diagnosed, new-born babies to be washed and checked over. There was a constant stream of people, old and young, until evening. Our brothers and sisters worked constantly, with only one short break at noon to visit the camp "cafe," where we ate boiling soup under a plastic and bamboo canopy.

The Japanese sisters were amazing to watch. They seemed so quiet and gentle when talking to them, delicate and sensitive. But when there was an infection to lance or a deep wound to wash, they went at it with a strong concentration that seemed totally unruffled by the tears or groans of the patient.

I spent a lot of time watching a young woman (again, probably older than she looked) volunteer from Vietnam as she washed babies who were between 2 and 15 months old. The fathers usually brought the babies to the hospital while the mothers rested or worked at home. I held each baby and spoke to each father, even if he spoke no English, although most of them did speak at least a little. Besides fathers, lab workers, the "baby-washer" and myself, there was a stream of curious children and adults who peeked in or came in unchecked just to see what was going on and find out who this strange woman, "the American," was. In these small rooms, no one seemed to mind when people came to watch the proceedings.

When the last baby was washed and wrapped and given back to the nervous father, who would hold it like it was a big soap bubble, I had a chance to speak to this attractive young woman and hear her story. She had brought her 11-year-old daughter with her on the boat from Vietnam. Her husband was in prison there, and she seemed to have some hope that he would be released soon and would try to escape by boat himself. Her boat had been attacked by Thai pirates, as most boats are, and she had been raped along with all the women on her boat. Fortunately they let the boat continue on its way, after robbing them of anything they had. She had tears in her eyes as she told this, but she never said anything to win my sympathy or my pity. It was her story and the story had played an important part in her life, so she told it. She smiled even as she told it, in her broken English, and I felt again how brave and strong these people are.

I saw several women being treated for syphilis which they had contracted from rapists on the boat from Vietnam. A long, slow, painful series of injections will cure them of this disease, but what can cure their spirit now? Though they don't seem bitter or angry, they can't help but be scared by the terror and misery of their life.

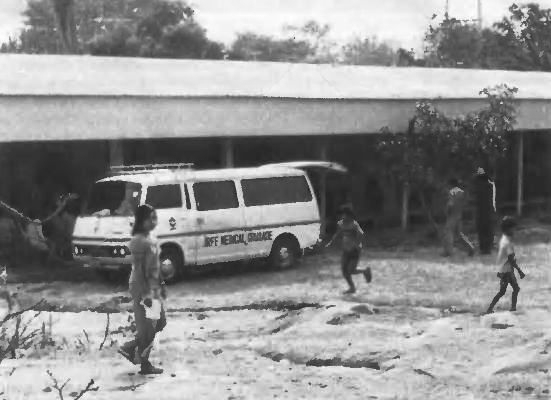

I was very weary at the end of the day and happily climbed in the van with the Japanese brothers and sisters to go to their home in a nearby town to spend the night. These Unification Church members seemed tired but happy on the way home. Some dozed, some talked, some sat together quietly.

Their home is very simple, a Thai-style house right beside a stream that rushed noisily past. The house stood amid an orchard of Thai grapefruits and jasmine bushes. After dinner, the members studied individually, either English, Thai, or Divine Principle. I slept, after a short prayer, so tired from all the new and intense impressions I had received. It was so very quiet and peaceful there, without traffic or noise of any kind except the stream running by endlessly. But I knew the people in the camp were not sleeping as well as I was. Each family in their tiny cubicle, separated from the next family by a curtain of woven bamboo. Hundreds of people in one huge building; children, young couples, old grandfathers, the sick and the healthy.

I didn't cry till I got home to Bangkok the next evening, and not until I was safely in my own bed. Suddenly everything poured in on me. All the children's faces; all the women, so many of them violated sexually and humiliated; all the young men who were strong and brave but helpless now to do anything for their country; all the young mothers looking at the future of their children wonderingly. I wept then as all their eyes and faces came back to me. I could understand God's heart and what He must feel as He looks at our world. I could understand True Father's decisions to take up this mission offered to him so many years ago. I was grateful that there are many people, like this medical team, in many countries who are giving their lives to do something about the pitiful situation humanity has found itself in.

Ikuko joined the Unification Church in 1973. For seven months she worked in Nichi 'chi Clinic which is run by the church in Japan. She arrived in Thailand in June of 1982.

I love one child at the camp so much that he almost feels like my own. His mother is still in Vietnam so he missed her very much. He comes every day to the hospital to visit me and I make a little time for him. Recently the "minors' center" was built which holds 200 orphans here in Thailand. Now I work in the surgery, but if I have time I like to make a puppet show or something to help in education. Under communism the children could not go to school because of soldiers and officials who fought against communism. I am afraid of their future.

When we cooperate with the Vietnamese workers they always smile, but their hearts are miserable. Sometimes I feel their heart so much that it's difficult for me to talk with them. When it's cold at night they can't sleep because they have so few blankets. Their eyes are swollen in the morning. Because of that I become so angry at communism. At this time we cannot witness to the Vietnamese people but I hope we'll meet some of them who can understand God's work.

Keiko was trained as a medical student before she joined the U.C. in 1975. From 1978 she worked in Isshin hospital.

I have only been at the Sikieu camp for three months so I don't have contact yet with many people in a deep way, but I know one lady very well.

Her father escaped from Red China so she was the second generation to escape from communism. She wished she could go back to her father's house in China, but she hates communism.

Through this, I realize that Asia is almost taken over by communism. Father said a long time ago that Korea, Japan, and Taiwan must unite, but I couldn't understand it until now.

Joined in 1979 and has always worked in Isshin hospital as a pharmacist.

When I came to Thailand at first I wanted to defend Thailand against communism, but now I am worried about the children's education.

I want to explain about the sanitation camp. Everything is bad: water, toilet facilities, their living places, even the air. The number of patients we see every day will decrease when these things are taken care of. One brother who recently went back to Japan started a water chlorination program. Since the water is being chlorinated our diarrhea cases have decreased.

We don't want to give only material things to the refugees, but especially moral education.

Toshiko joined in 1977. She worked for two years at a University hospital in pediatrics, and from 1979 to 1981 in another hospital in surgery. She came to Thailand in January 1982.

I feel very sorry because the refugees have many suffering experiences. I have none like that, so I think I have learned how to control a large group of people in the camp. The people used to crowd in and almost overpower me since I was the first to receive their prescriptions and get their medicine. But now I can handle the situation.

They are more mature than me. I want to learn how to love. I couldn't love myself and give love before I joined the Unification Church. But here at the camp I learned already to give more and more of myself and ask nothing from others.

Now, after working and living together with them, I respect the refugees very much.

Joined the church in 1970 and worked for more than a year at Isshin hospital. She has been in Thailand for a total of 18 months.

Our situation is not very good. On the other hand all camps have problems. Actually our camp is even better off than others in many ways. Even though we don't have enough money or medical equipment we must give 100 percent of ourselves, our heart. Through contacting us I hope the Vietnamese can get inspiration from God and feel His heart. We must give to them things in His place like comfort and hope for the future. Vietnamese people are being resettled. I hope they can meet True Parents in their new country of resettlement and learn why their own country has had such a miserable situation and what they must do to get it free again.

Joined in 1975 and continued his medical school and passed his final exams for medical school in 1981 and from then on worked in the Isshin hospital.

Before I came to the camp I didn't like Vietnamese. I thought they were barbarians. But when I met them I was surprised to come to know that they have a very high culture. For example they speak French and English very well. They are very honorable and have respect for elders. This is even expressed very much in their language. I learned how sad a person is without belonging to a country of his own: no visa, no passport, illegal immigrants.