![]()

The Words of the Cooper Family

|

|

The Words of the Cooper Family |

Perhaps we should explain what we all get up to at our Chung Pyung training center with liberating spirits and healing. What about putting a section in the 'about' on our site which explains about returning resurrection and the relationship between spirits and people on earth and how to manage that reality in a positive way. The following is an article from Timesonline:

The Rev Canon Ken Gardiner has spent the past five decades exorcising demons from his flock in commuter-belt Kent. The octogenarian, in dog collar and grey blazer, could be straight out of The Exorcist -- the calm and authoritative man of God with an unshakeable belief in the power of Jesus. Pouring me a cup of coffee in his bungalow near Rochester Cathedral, where he is a canon emeritus, he takes me on a tour of a life on the dark side of Christianity.

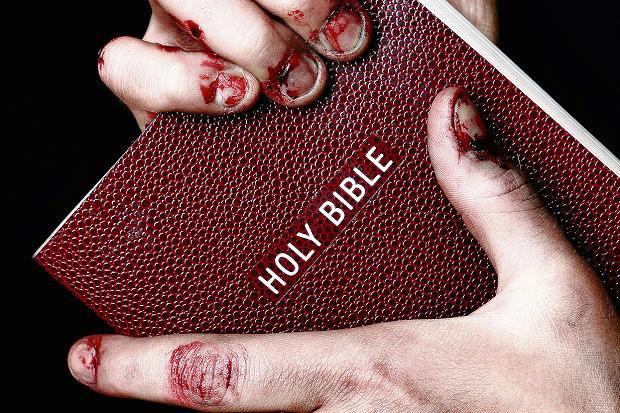

"How many exorcisms have I done? Things that go bump in the night -- countless, but people needing deliverance, perhaps 40-plus," he says. His tools are the age-old weapons of the Anglican exorcist -- prayer, holy oil, the cross and Bible. In his book The Reluctant Exorcist he recounts a lifetime of battles with demons. There's the mother who keeps waking to find that shoelaces have bound her wrists, the customs officer possessed by an evil spirit, people talking in tongues and the Satanist university student.

This case illustrates how a modern exorcism can come about. During a drink on the last day of term, the student told friends that she had become deeply involved with a Satanic society and wanted to escape. The friends brought her to Gardiner's house, where she went rigid, her eyes rolled back in her head and she began saying "what sounded like 'sausage' ", over and over again. After a few minutes, Gardiner realised that she was actually saying Jesus backwards.

He'd have been forgiven for throwing her out, thinking it an elaborate end-of-term joke, but Gardiner had no doubt that she was possessed by a demon. He pulled out his Bible and asked her to read a passage, which she did "backwards and at an astonishing speed". He made the sign of the cross over her and "she uttered a roar of anger … and a voice, coming from her, screamed 'kill her'. She put her head down and tried to run into the wall behind me." It was only after hours of spiritual struggle that the demon left her body "with a loud scream".

Gardiner is one of the Church of England's 44 exorcists, one for every diocese, appointed by the Archbishop of Canterbury. In 21st-century Britain, where one in four of us will apparently suffer a mental illness in any given year, combating unusual behaviours with exorcism might seem outdated. However, if you talk to mental health professionals in the NHS, a different picture starts to emerge.

Dr Rob Waller, a consultant psychiatrist and an honorary clinical lecturer at the University of Edinburgh, used to work for Bradford District Care Trust, and was part of a medical support group for the local Catholic exorcist. It met monthly to discuss cases and whether they should be dealt with by church or doctor. "There was a similar set-up with local imams, and the Church of Scotland has links with psychiatrists and considers exorcism."

The relationships were established after a case in 1974 when a man tore off his wife's face with his hands after undergoing an all-night exorcism in his local church. The man was reported to have been discovered bloodstained and naked in the street shouting "it is the blood of Satan". The Archbishop of Canterbury at the time, Dr Donald Coggan, then laid down strict guidelines for the ritual. Exorcisms, now termed by the Church as "deliverance" (from evil), were to be undertaken only by an appointed diocesan exorcist after consultation with a doctor.

Although exorcism is an area of its ministry that the Church of England shields from public view, it seems that demand is rising. A report, A Time to Heal, published by The Archbishops' Council in 2000, has a chapter headed Deliverance from evil, which says that "the deliverance ministry has spread in the Church of England".

Waller thinks that every consultant psychiatrist will see a "handful of patients" in their career requiring "some kind of deliverance ministry". He tells the story of a man brought to hospital by the police. "He was talking about being pursued by evil, about voices in his head. We contacted the [hospital] chaplain, who prayed with him, and there was follow-up from a local church. There was definitely no mental illness, quite clearly not schizophrenia. The situation resolved itself without treatment," says Waller, who is director of Mind and Soul, an organisation exploring Christianity and mental health.

Professor Robin M. Murray, head of Psychiatric Research at Kings College's Institute of Psychiatry, who this year was awarded a knighthood for his services to medicine, says: "Not all psychiatric problems respond to conventional treatments. So while I don't know of any scientific evidence that exorcism works, I would have thought it reasonable for a [hospital] chaplain to carry this out."

The NHS has often been criticised for over-reliance on drugs in its mental health treatment. Perhaps this partnership forms a more pastoral approach? According to Professor Christopher Cook, who has written a new set of guidelines on spirituality for the Royal College of Psychiatrists: "There is a spiritual dimension to all health-related issues and exorcism might be appropriate in some cases."

Not all his colleagues agree. Dr James Woolley, consultant psychiatrist at the Springfield Hospital in southwest London, does not believe in the concept of demonic possession or exorcism. The DSM-IV, known colloquially as the "psychiatrists' bible", cites many psychiatric syndromes characterised by a patient believing that he or she is possessed and, for that reason alone, Woolley says, it would be "reckless and unprofessional" to recommend exorcism as an avenue of treatment. "The psychosis could get worse, and being in a highly paranoid state is associated with the risk of harm primarily to yourself and potentially to other people," he warns.

The Department of Health is keeping a low profile. Charles Whitney, a spokesman, says: "Exorcism is not something we have policy on or can comment on." Others are similarly reticent. The Archbishop of Canterbury's personal adviser on exorcism admitted that there were internal disputes over the secrecy surrounding the subject, but I was still refused an interview.

None of this matters to Gardiner. He doesn't doubt for a second that his lifetime's work has been worthwhile. "I have seen exorcisms succeed," he says. "People came to me in a state and, in the name of Jesus, I've commanded whatever was there to leave. Their families tell me, 'I've finally got my wife/son/daughter back'," he smiles. "So if it wasn't using the name of Christ [that worked], you tell me, what was it?"