![]()

The Words of the Downey Family

|

|

The Words of the Downey Family |

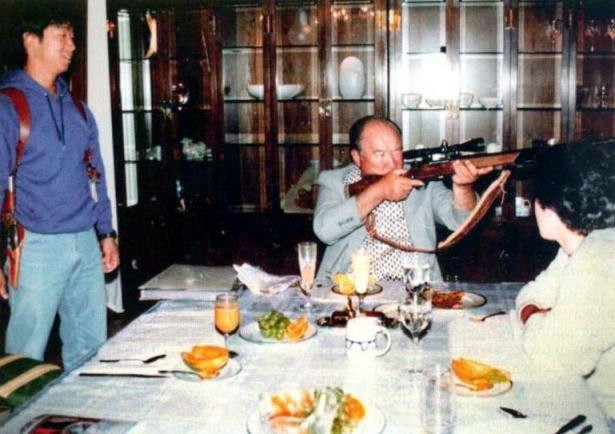

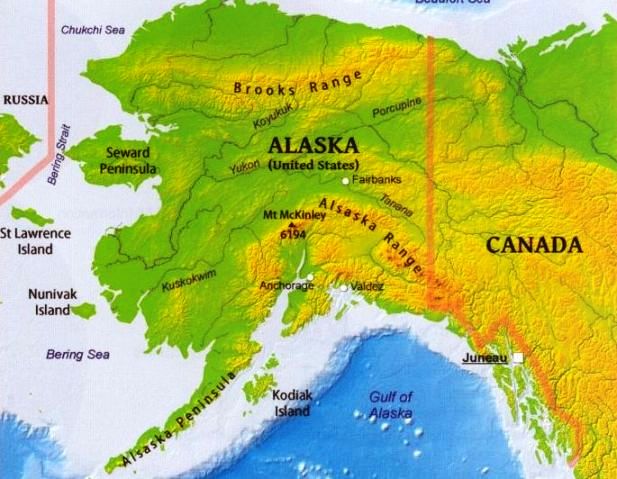

Alaska is a sportsman's paradise. Opportunities for world class fishing for salmon, halibut and other species abound. Once you fish in Alaska's rivers, streams, lakes and surrounding waters any other place is a letdown. I suppose the same can be said for hunting. People come from around the world to hunt in the Last Frontier. Trophy species such as the legendary brown bear, moose and mountain goat attract hunters from the lower forty-eight' as well as Europe, Asia and South America. Caribou, white tail and black tail Sitka deer are prized for meat by the locals and smaller game like ducks and rabbits are taken in season. For residents of Alaska, hunting is not only a sport but a way of life. Hunting to put meat in the freezer and a familiarity with firearms is a normal part of life for most men and many women too.

When followers of Rev. Sun Myung Moon arrived in Kodiak in 1980, they were not necessarily the pioneer or outdoor types. Most of them were probably more comfortable raising funds, giving lectures, sermons or working in an office. For the most part, when they moved to Kodiak to build and operate a seafood processing plant, they took to the local ways like fish to water. Fishing and hunting became de rigueur for our members. Running a small boat, catching and cleaning a fish and shooting and then butchering a deer became our new skills.

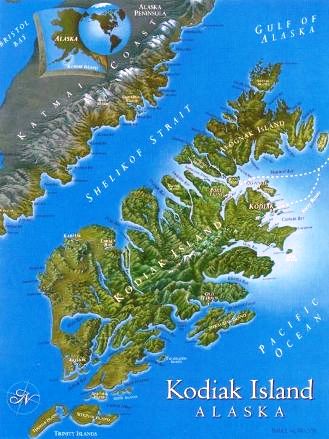

Of course, True father's vision was much bigger than just a business. For Father, the ocean, mountains and wilderness of Alaska were ideal training grounds for members and leaders from around the world. Over the years, lie brought church members and leaders from Korea, Japan and many other nations to experience the lifestyle and to train them personally. For several years, he brought Korean university professors, put them in rain gear and boots and trained them on the rivers and seas around Kodiak Island. He also brought forty Japanese women, all blessed in marriage to American husbands, to work and live the lifestyle. They sacrificed their family life for six years and brought a measure of stability and success to the operation. Later, Father sent them out to pioneer seafood businesses around the world.

Summer after summer, Father led the worldwide movement from North Garden. In the process, those of us working in Kodiak witnessed firsthand True Father's daily life. He was at the dock every morning at oh dark thirty, except in the most inclement, dangerous weather. From first light to last light each day, Father labored on the ocean. The marine climate around Kodiak and the sea conditions are more often than not rough, wet and cold. Father always went out in an open boat as close as possible to the sea. There was never a chance for even ten minutes shelter from the harsh environment. He ate rice balls, Hershey's chocolate bars and bit-o-honey for lunch without a pause in his fishing. He urinated in a bucket like everyone else. Father's boat almost always came back after dark. Of course, they held dinner for him. Over the evening meal a lucky few were able to share a few more intimate moments with True Parents. Usually the day's events were reported and discussed. Leaders took this time to report and to seek Father's advice and direction for their activities. After dinner Father began speaking. For two, three or even four hours, Father poured out his heart and directed the worldwide movement. It was always after midnight when Father retired to his rooms for a few hours' sleep. Before long, he was up again and ready to go back to sea. Mr. Joo Chan Choi, International Seafoods of Alaska (ISA) president, took to sleeping on the floor in front of Father's door, because several times Father was up and out the front door before anyone else in the house was awake. We watched Father live this way day after day, year after year and tried to keep up.

We that were part of the permanent staff tried to live the life as much as possible. We fished, worked on boats and in the fish-processing factory. We all owned guns. It was almost required. Every year at the end of the salmon season, in late August or early September, Mr. Choi held a halibut fishing and hunting contest in appreciation of all the members' hard work. As far as I know, only men participated in the hunting but everyone fished. Misako Whitmore won first prize by landing a 322-pound halibut one year.

Prizes were awarded in several categories. Pistols, rifles, shotguns, knives, fishing rods and reels and the occasional so- called assault rifle were handed out to winners. Sometimes, I wonder what happened to the M-16 rifle that Masako san won.

Mike

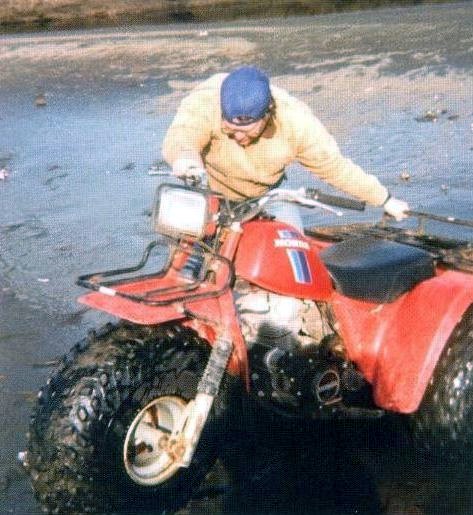

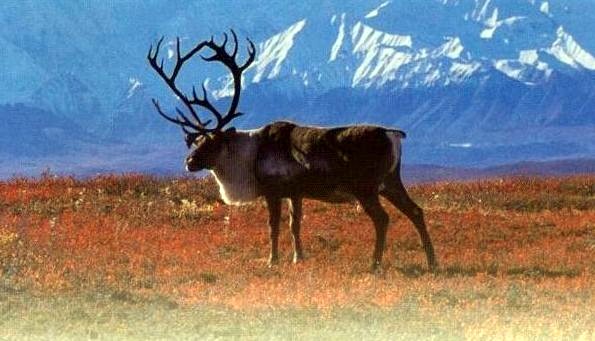

Downey struggling with an All-Terrain Vehicle (ATV) over the

difficult Alaskan terrain, and with a recently killed caribou that

provided meat for the members working for International Seafoods of

Alaska. In Europe, caribou are called reindeer. In Alaska only the

semi- domesticated ones carry that name.

Living in Alaska was a dream-come-true for me. I loved working on the ocean. Fishing was just an excuse to be on a boat at sea. Likewise, I enjoyed shooting. Getting out in the vast Alaskan wilderness was an added bonus. During one of the annual hunting contests, another guy and I were dropped off by skiff in a cove on the west side of Kodiak Island. We waded through the surf, crossed a narrow beach, chose a likely slope and started up the mountain. It was late August and the plan was to hightail it up to the summit and (we hoped) surprise a black tail buck when he broke cover to graze in the warm sunshine. The thick alder cover slowed us down, but we worked our way up through it knowing that it would yield to alpine meadow somewhere around the eight-hundred foot elevation. My partner was somewhat of a fireplug with two pistons for legs. Before long, he was well ahead of me and showed no sign of slowing down for me to catch up. I just let him go. By the time I got out of the alder, he was long gone. Winded from the climb, I sat down to rest and take in the view, which was spectacular. The mountains and valleys seemed to go on forever in three directions with the waters of the Shelikof Strait forming a backdrop. No sign of human habitation was visible anywhere, no buildings, vehicles or roads. It was the very definition of pristine. The higher peaks in the distance were snowcapped, even in August. The lower mountaintops were almost treeless, covered with low grasses and lichens. Vegetation covered the valley floors, mostly thick alder but interspersed with pine forest. Thick moss hung from the lower branches creating a sub-tropical feeling. High overhead, clouds drifted across the blue sky casting shadows, changing the color of the mountains, forests and the sea. Once my heavy breathing abated, all was silent. Slowly I began to notice the sound of running water coming from a small brook about ten yards to my left. The water was so cold it hurt my teeth when I took a drink. I thought once again that this is why people climb mountains.

For a long time, I had no inclination to move. Slowly I became aware of a sound. At first it was far off, a low grumble and a roar. I sat up, listened more closely and looked around. What was it? I scanned the skies for aircraft. The sound got louder and my eyes were drawn by it to the long narrow valley directly in front of me. As I listened, the direction of the grumbling roar became clearer. It was moving down the valley toward my observation post. Now it sounded like it was a diesel truck roaring down the valley at full throttle. I guess the valley was about three miles long. By the time the roar had gotten to the halfway point, I began to hear crashing sounds of breaking branches. Next, I could hear actual grunts. My god, was it a bear? What else could it be? I had my binoculars out by this time and focused on what I perceived as the path of this monster. There it was. I could clearly see the crashing movement of something big moving down the valley through the heavy underbrush and pine trees. Now it was more like a freight train tearing down the valley in a straight line not moving right or left to avoid brush or trees but running over them. Finally, I began to catch glimpses of the beast. It was huge. A mixture of honey brown and a darker brown with a huge head and shoulders, it galloped on all fours with its head down. Although I was high above on the hillside, in little danger of it charging me, I felt the thrill of fear grip my belly. At end of the valley where the small stream emptied into the cove, the cover became sparse and the bear was clearly visible. It turned on a dime, splashed across the shallow water, charged into the alder and up the opposite hillside from my spot. Without slowing down he climbed a third of the way up, rounded the mountain and was gone. The Kodiak Brown Bear, largest in the world with no known predators, why was he running? I have no idea; maybe he was late for lunch.

On another day, I was hunting off the road system with another guy. It was a warm October afternoon and we were out for a walk and for meat. We parked off the dirt road and started up the mountain through the alder and pine forest. As always, it was rough going and by the time that we had cleared the alder, I was soaked through with sweat. As often happens, we separated and each followed our noses in different directions with a promise to meet back at the truck an hour before sunset. I could have climbed higher, but I decided to move around the mountain. Through a large flat area, I followed a small stream amidst the thinning pines and after a short time came upon a football-field-sized' clearing with a lake in the middle of it. It was downright pretty to look at. As was my habit, I found a small rise in the sunshine and sat down for a rest. The stream that I had followed in meandered through the grass of this flatland and fed into the lake about seventy yards away. I took out my binoculars and glassed the lakeshore looking for a deer drinking. The edges of the lake looked very marshy, with knee high grass most of the way around. The far end of the lake appeared at first to be a brown mud bank devoid of grass. On closer examination, I realized it was a beaver dam. I started looking for the engineer. A short time later, I spotted two Vs in the water moving from the far side of the pond toward the dam. When they got to the dam one after the other, two beavers climbed out dragging pine boughs four inches thick and five feet long.? They moved the branches into place, trimmed them and packed them down. Then they in turn slid off the clam and dove down under the right side. A few minutes later, they reappeared under the left side of the fortress-like structure. Next, the Vs glided back across the water to the far side and they lumbered out of the water and into the pine forest. Not too long after that, they re-emerged with more building material and headed back to the construction site. I watched them for almost three hours. Back and forth, back and forth, it was fascinating. At one point, I lay back on nature's mattress, closed my eyes and napped in the warm sunshine. When I awoke, they were still at it. I clearly understand where the expression "eager beaver" comes from. Finally, I had to rouse myself, saddle up and head back to the rendezvous. On the way, I stumbled across a yearling, dropped it and butchered it out; meat for the freezer.

Hunting on the Alaskan Peninsula is quite different from hunting the mountains of Kodiak Island. The main reason is the terrain, which on the Alaskan Peninsula is all tundra. From the air it looks flat with a few rolling hill and is dotted with what seems like a million lakes. From the ground, the tundra is not flat at all. Hue to the thawing and freezing of the ground above the permafrost, or permanently frozen soil, the earth is shoved up into moguls, tiny hillocks anywhere from two to six feet high. Some of the valleys created by these hillocks are small enough to step into and break a leg. Some are big enough to swallow an ATV. It is a treacherous landscape. Several species draw hunters to the area including moose, brown hear and caribou. Caribou, a large species of arctic deer, still roam the tundra as I imagine the buffalo once roamed the plains. They are big animals with magnificent velvet covered antlers. They migrate in huge herds, as many as mow animals, to and from winter and summer grazing grounds. If you are there at the right time of year, you can watch the Alaskan Peninsula herd approach and swim the Egegik River several miles upriver from the village. Once I sat on hill and watched the herd cross for four hours. A trophy hunter can glass the herd and chose the bull that he wants, track it and bring it down. I was a meat hunter. I was interested in shooting an animal that was in a convenient place to get the meat out. I've shot animals a hundred yards from camp.

I guess I would have been happy if a good-sized bull would have wandered right into camp. The area of the peninsula just north of the Egegik River and up to Big Creek was a known calving area. Cows would drop out of the herd, give birth and spend six months raising the calves before rejoining the herd on its way back south. So cows and calves were plentiful and are good eating.

The tundra was truly vast, and we usually used ATVs (Honda three- and four-wheelers) to hunt it. One day, I was on a three-wheeler about four miles behind Bartlett's Lodge enjoying the afternoon sun and looking for some meat. I was on a small hill and glassing the surrounding area. Seventy yards to my right, I spotted a good-sized buck with a nice rack, standing knee deep in a medium-sized lake. I was packing my Springfield Armory M1-A-1 chambered for.308 caliber. I had it loaded with full-metal-jacketed rounds, which pack a punch but does minimal damage to the meat. At seventy yards even with open iron sights, I wasn't going to miss. I got down in a sitting position with the sling around my arm for support, got a good sight picture, put the top of the front sight blade on the buck's left shoulder and squeezed off a round. I know I hit it but it did not go down. I took a quick look with the binoculars and saw blood on the flank. I fired another round and (Barn!) this time the animal staggered and began rushing into deeper water. Barn, barn, two more rounds and he went down. The problem was he was now half-submerged in the center of the lake. To kill game and fail to recover the meat is illegal in Alaska. It is known as "wanton waste." I had to get the beast out of the water. I packed up my gear and motored over to the lake, which was surrounded by alder shrub and stunted pine trees. With a little difficulty, I was able to find my way through to a narrow sand beach. It was early October, the air was brisk and I knew the water was going to be colder. I calculated that I was going to need some dry, clothes to bike back to camp, so I took off my boots and all my clothes. I put my belt between my teeth and waded and then swam out to the middle of the lake. Luckily, the caribou was only half-underwater. I had done this before with a moose that sank to the bottom and had to dive for it.

Wrapping the belt around the beast's neck was not a problem. I slowly towed it to the beach. Once I had dragged it three feet up onto the gravel and sand, I began the process of field dressing it. The first step was to position the animal so that I could make a cut from the throat, down the sternum to the genitals. Next, I had to cut through the sternum in order to remove the heart, lungs, stomach and other organs. It was a big animal. I put it on its back with my knees spreading the rear legs and using my elbows to hold the front legs apart.

I was using a K-bar (a seven-inch long knife) to break the thick bone. I struck it once, twice and on the third strike, the pointed blade glanced off the hard bone and drove an inch and a half into my thigh, six inches down from the crotch. Of course, I pulled it out and the blood pulsed out in a three- inch geyser. First came shock and then the realization that this is going to take some fast action. Still naked, I looked around to find something to stop the bleeding. The belt was still around the buck's neck and was in reach. I used it to fashion a tourniquet and cinched it tight above the wound. The bleeding slowed to an ooze, but I knew I needed to get back to Dodge (slang for "town"). I needed stitches. Before I could do that, I had to finish the field dressing, get the caribou on the three-wheeler and get it off the tundra. I put on my dry clothes and began to wrestle the carcass, which weighed in excess of two-hundred pounds, onto the rear of the ATV.

It was no easy task. After three attempts, I managed to get it balanced on the Honda and tied down with cord. It was a at least four miles back to civilization; that is, Bartlett's Lodge. Under ideal conditions, I could make it in twenty minutes, but I was losing blood and trying to keep the caribou on the bike. The heavy weight over the rear wheels made it impossible to keep the front wheel on the ground. Like any tricycle, contact of the front wheel with the ground was the only way to steer the bike. Although I leaned as far forward as I could, I could only rarely coax the front wheel to kiss the earth. All I could do was go straight ahead until I came to an obstacle, dismount and wrestle the bike on to a new course. Often I had to stop and re-secure the animal to the machine. I had a handheld VHF radio and used it to contact the lodge. Helen (the lodge owner) came up on the radio, and I told her I was on my way in with a knife wound. She said there was a spotter pilot in the bar drinking coffee. She offered to send him up in his Piper Cub to look for me. Twenty minutes later, I heard and saw the plane circling three miles to the southwest. I couldn't get him on the handheld, so I plowed on. An hour and a half later, I pulled up behind the lodge exhausted but relieved. I went directly to the social center (the bar) and was greeted by a small crowd of whiskey drinkers that were discussing sending out a search party. The first order of business was to get the tourniquet off, wash and dress the wound. Three middle-aged guys were intently interested in what had happened and the condition of the wound. One guy told me it was important to get the wound stitched up right away and said he could do it with a sewing kit he had in his pack. I asked him if they were doctors. He replied with assurance "No. We're lawyers." I said no thanks and waited for the medivac out of King Salmon (the nearest town that had a clinic with actual medical staff).

When the plane rolled to a stop at the gate in King Salmon, it was met by paramedics in an ambulance and the Alaska State Troopers. The troopers had heard that a stabbing victim was coming in from Egegik. They were there to collect evidence and to fly back to the village to arrest the perpetrator and bring him or her in. With a red face, I had to tell them that I had stabbed myself.

Over the years that True Parents came to Alaska, they often brought along one or more of their children. Beginning with Heung Jin nim in 1983, almost all of the children came at one time or another and participated in fishing or other outdoor activities. The boys were into shooting and riding ATVs. Once, Kook Jin nim, Hyun Jin nim and Young Jin nim came out to Egegik to ride ATVs. I tried to give them a safety lecture before they started out but they ignored me and tore up and down the beach like wild men. I was very worried when they headed out on the tundra. I made an attempt to follow them but couldn't keep up. They returned later on foot. It took three clays to find the ATVs.

Hyo Jin nim was known as an avid deer hunter. When he came up, he wanted to hunt for big game. The Roosevelt Elk, the largest of the North American elk, is not native to Alaska but was introduced to Afognak and Raspberry Islands in 1928. Bulls can weigh in at almost 1,300 pounds and stand as tall as six feet at the shoulder. We figured this would be a great challenge for Hyo Jin nim. Captain Allen Hokanson was an experienced Alaskan hunter and was tapped to head up the expedition. The plan was to book the "U-Rascal," a local charter boat owned and run by Captain Chris Fiala, load it with supplies and use it as our headquarters and bunk house during the hunt. Groceries, cooking gear, ammunition and hunting licenses were all bought in advance and loaded onto the boat. When Hyo Jin nim arrived, we were ready to go. The next clay, after Father had finished speaking and had gone out to fish, Hyo Jin nim sent word down that he was ready to go. He wanted to leave after lunch. We hit the clock by 2:00 PM and cast off. Onboard were Hyo Jin nim, Captain Hokanson, Captain Fiala and I. It was about two and a half hours to Afognak. The weather was overcast, with some light showers. The sea was flat calm. We arrived at Afognak Bay without incident around four-thirty. The captain motored down the bay looking for a good anchorage with easy access to the beach. We dropped anchor thirty feet off the beach and I assumed we would soon have a nice dinner and a long nap. That was not to be. Hyo Jin nim was well rested and anxious to get started.

This was late August, after five o'clock and the sun would be going down in a couple of hours. Hyo Jin nim said it would be a good condition for us to get on the beach and head up the mountain right away. He said we would be hack before dark. So we grabbed rifles, ammunition and day packs and took the skiff to the beach. Allen distributed to each of us a bar of chocolate, a hunk of cheese and a hunk of bread. These, along with the tube tent in his pack, were our survival gear. With Hyo Jin nim in the lead, we started up the mountain. Afognak is a relatively low-slung island and for that reason is home to a fairly large logging operation, but we could see no sign of human habitation or activity. The slope was steep and the thick alder made for tough going. Also, Alaska is a very wet place. Sweat from exertion and the moisture from the vegetation combined to soak a climber to the skin. By the time we broke out of the tree line at around six hundred feet of elevation, I was soaked through and through.

Above six hundred feet, the vegetation thinned out and we climbed through the grass of an alpine meadow. Another four hundred feet above us was a peak and beyond that a series of peaks that together formed a ridgeline. In the fading light, we walked the ridgeline and scouted for elk sign. Two black tail does appeared but we held off. We were elk hunting.

In the last light, we looked behind us and knew there was no way we were going to get down the mountain that night. Once the sun set, the wind picked up and being wet we became very cold very fast. We needed shelter and a fire.

Allen contacted Chris on the hand-held and told him we were spending the night. At 1,200 feet, there were no trees or other vegetation so we moved down to find a windbreak and something to make a fire with. After ten minutes, it became so dark that my hand was barely visible in front of my face. We found a slight depression that might block the wind a little. We dropped our packs and started looking for firewood. Little wood was there and most of that was nearly waterlogged.

We gathered what we could and tried to start a fire. It took an hour or longer before we coaxed a small flame out of the damp pile of kindling. For the longest time we continued to feed wet sticks into the flame. Drying out the wood absorbed all the heat from the fire so precious little heat was given off to warm our frozen fingers. In particular, Hyo Jin nim was worried about his hands. He was a musician and his fingers were important for playing the guitar. The three of us hunched over that pitiful fire and tried to get warm for hour after hour. It was the longest night of my life. We walked around, stamped our numb feet and flapped our arms in a futile effort to warm up. We took turns dangling our wet socks over the flame but that merely dripped water on the flame, threatening to extinguish it. Finally Hyo Jin nim gave up on the fire and said, "Let's get some sleep."

Allen broke out his survival tent, which was like two vinyl garbage can liners with a string running through it. We set it up as best we could and crawled in. We laid in close skin touch to each other because that was all the room we had. In a short while, the three of us began to shiver. Our teeth began to chatter. This was the first stage of hypothermia. We tried for what may have been an hour but there was no way anyone of us was going to fall asleep.

Hyo Jin nim decided to get up and start the fire. Another hour later and we had the same insufficient fire going again. We spent the rest of the night huddled over that lire, hoping for heat. With time on my hands and nothing else to be done, it was a good time to pray and so I prayed for daylight. I don't know how the others occupied their minds; we did not converse.

First light brought new hope and with a cold breakfast of the remains of yesterday's survival rations, we broke camp and started out along the ridgeline with our eyes peeled for the elk.

We hunted for several hours but having no sleep and little food we soon decided it was time to find our way back to the U-Rascal. By this time, we were well away from the point where we had ascended, so Allen called Chris and asked him to bring the boat around to Marker Bay with the idea that we could walk down from where we were. The way down looked straightforward. It was a steep slope going all the way down stream. The slope was no problem. I slid down most of the way on my buttocks, using my rifle butt to slow down. When I got to the bottom, Hyo Jin nim and Allen were nowhere to be seen. I was on my own. I quickly found the stream and an animal trail that ran along the bank. At first, the trail seemed to be my highway out. Before long, as it descended, it became difficult to follow. It went up a hill for six or eight feet and then down six feet again -- up again, again down. I realized I was running on empty. I thought then that walking in the streambed, which was strewn with boulders large and small, would be easier. The boulders were wet and slippery and I was wet to the waist. I abandoned the streambed and went back to the trail. I began stumbling.

I realized I was in danger of falling and injuring myself. I kept going, wondering if the others were in front of me or behind me. Finally, the terrain began to flatten out and I found myself walking through an area of pine trees and low brush. Here,

I heard two rifle shots. I knew the sound had come from in front of me and that somebody had killed an animal, probably a deer. Who would carry it out? I would be lucky to get myself out. Next, I began to hear noises, voices and animal sounds that I knew were not there. I was hallucinating.

For the first time, I began to think I might make it out. I sat down and looked up at the treetops. I had a radio but even if I could reach somebody, I was pretty sure they couldn't get a helicopter in here. I thought, "I have only two choices. I can lay here and die, or I can get up on my feet and walk out." In a second, I decided. I was not going to die here.

I rose and started putting one foot in front of the other. Down and down I walked. Several times, I stumbled and once I fell, but the crisis was over. I kept going. Eventually I came to the mouth of the stream and found the U-Rascal at anchor. I hailed the boat and they sent the skiff to get me. Of course Hyo Jin nim and Allen were back with the deer that Hyo Jin nim had bagged and Allen had carried out. All they said was "Where the hell have you been?" Back in town everyone wanted a report but I didn't say anything. Later I heard that Hyo Jin nim had told someone about the adventure emphasizing, naturally, how difficult it was and how tough we were to have survived. This eventually reached Mother who later scolded Mr. Choi. This was all a part of life in Alaska.