![]()

The Words of the Kaufmann Family

|

|

The Words of the Kaufmann Family |

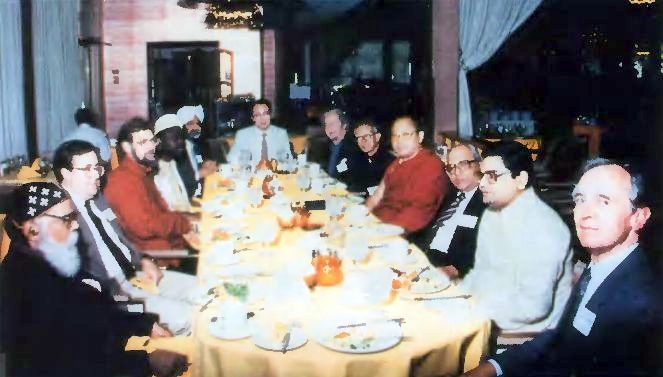

Rev.

Kwak has lunch with some of the major religious leaders attending the

interfaith conference in Harrison Hot Springs, Canada, in August

1987.

Question: How did the Council for the World's Religions come into being?

In order to understand the CWR, it is necessary to know how the International Religious Foundation got started. Of course, long before the IRF formally came into existence, Father was working toward the goal of establishing a unified religious world. From what I understand, Father devoted a significant portion of his resources to interfaith work even during the early days when the movement was very poor and the members were struggling to eat. Certainly the name Unification suggests an ideal of inter-religious cooperation and harmony. The CWR was not a sudden surprise with no prior foundations. I am sure Father had planned for this from the very beginning.

Father's clear commitment to the world's religions can be seen in how he formed the Unification Theological Seminary in the United States. The Seminary was founded in 1975 with a completely interfaith faculty. It's unheard of that a religion, especially a new religion, would subject its future leaders to teachings from adherents of other religions. Yet students at the Seminary continue to be taught by rabbis, Christian ministers, Muslims, Buddhists, and so on. In 1975, Dr. Young Oon Kim was the only Unificationist on the entire faculty!

Father regards all authentic religions to have been inspired by God. They exist as part of God's efforts to fulfill His ideal. Each one has something special to tell us, some special insight and unique beauty. Ultimately, Father wants the Seminary to become an interfaith center for the world, the center of the study of God and religion in all its expressions. Efforts to realize that vision began happening at the Seminary with small conferences that eventually blossomed into the International Religious Foundation.

An energetic, unpredictable genius and dear friend of mine named Herbert Richardson began these conferences. In 1977 he brought some of his friends and former students from Harvard and the University of Toronto to the Seminary to enter into dialogue with the Unification students. He thought it would be advantageous for the students at the Seminary to exchange views with traditional Christians so they could develop their theological abilities and their capacity for self-expression, as well as learn the true nature of the Christian tradition. These small conferences between Unificationists and traditional Christians were the first stirrings of our great interfaith work.

The people that came to these conferences were very inspired, and it was through them that we started to develop a network among North American Christians. Many different denominations were represented; liberal Christians and evangelical Christians were two major divisions. One of the curious things that happened when these groups mixed was that the liberal Christians would take us aside and say, "You know, you Moonies aren't so bad, but it's those evangelicals that drive me crazy." And vice versa! It was through this that we realized the need for ecumenical conferences so that Christians themselves could speak to each other, resolve their own internal differences, and thereby strengthen the Christian religion. Father has said that Christianity has the task of protecting the moral foundation in America and the Western world but that its internal divisions render it incapable of fulfilling its God-given responsibility.

Gradually, as more and more scholars of religion gathered to confer under Unification auspices, the process and network eventually became formally established as New ERA, the New Ecumenical Research Association.

New ERA continued to grow and soon became known as a body that was willing to sponsor conferences designed for the strengthening of religion per se. People who had no forum for their ideas elsewhere discovered that New ERA was open to creative and innovative ideas. This breath of fresh air into the world of conferences on religions naturally attracted large numbers of religion scholars. But the numbers were less important than the kind of scholars we attracted. These were the creative, risk- taking people, like Simon of Cyrene and Gamaliel in the Bible. They were those who put integrity ahead of pomp and circumstance, those who were willing to look in unusual places for the work of God, rather than looking for the next opportunity to advance their own career in the academy. You have to be a little crazy and daring to work with the Moonies.

Sri

Shrivatsa Goswami, Hindu consultant of CWR, describes legends of the

Ganges for participants at the intra-Hindu conference on "Maki:

Its Experiences and Expressions," held in November 1986 in

Varansi, India.

In 1980, during a meeting among Father and the New ERA advisors, the International Conference on God: The Contemporary Discussion also known as the God Conference was founded. The God Conference moved the work of New ERA onto the global, intercultural, and inter-religious scale. It had been heading that way all along, but now the focus was explicitly the relationship among all the world's religions, not just Christianity. It was scheduled to occur over God's Day each year, and God was the center of attention. Father was happy with this. The first world-level interfaith activity was, and continues to be, the God Conference that takes place every year. It is like an internal ICUS.

At the fourth God Conference, held in Korea in 1984, Father founded the Council for the World's Religions, which is distinct from the God Conference, though similar in terms of what it seeks to achieve. Like the God Conference, inter-religious relations are the object of concern. The difference, however, is that the CWR conferences are opportunities for the direct encounter of the faiths. It is not just a "research association," but a dialogue between and among believers. The participants still include scholars, but they speak from the standpoint of their own faith, as practicing Hindus, Jews, etc., not just on a topic of theological study.

An important dimension of the CWR is the addition of actual religious leaders as participants at the conferences. Father's idea is to bring together a group of people who are directly involved in religious action and advocacy. He would like to see the greatest and most respected leaders of the religious world meet and work together to represent God and the harmony of God's ideal to their followers. In a way, the word Council in the title is a bit premature. It is not yet a council. When it really becomes the Council for the World's Religions, it will be sought after for advice in solving world problems and will be able to provide spiritual guidance based on the cooperative deliberations of the world's foremost religious leaders and their representatives.

Even though we are not yet a council of that stature, the essential nature and process by which we move is consistent with that great goal. Already a significant number of prominent religious leaders have involved themselves in our work. At our conferences, these leaders are able to encounter people from other cultural and religious spheres whom they would not ordinarily meet. They learn to love and respect the differences they discover, and afterwards they can return to their own communities and stand as advocates for greater toleration and mutual respect.

Dr.

Frank Kaufmann chats with Father Albert Nambiaprambil, advisor to the

Vatican Secretariat on Non-Christian Religions, at a CWR conference

in Eibsee, West Germany.

Question: Could you explain more clearly the difference between a CWR conference and, say, a New ERA conference?

At New ERA conferences it is perfectly acceptable to have a participant who is, for example, an agnostic but at the same time an expert on African religions, or a Jew who is an expert on the New Testament. For where scholarly theological research is concerned, a person's private religious beliefs are not supposed to come into play. (Of course it often happens, although some scholars prefer not to admit it.)

But at a Council conference, when somebody speaks, he speaks out of the depths of his own religious convictions. Council conferences move away from strictly academic considerations to the place of actual religious encounter.

A participant at a CWR conference will find himself in the position in which the deepest and most important aspects of his personal faith are challenged -- not necessarily in a direct or antagonistic way, but rather by the mere fact that there is someone else in the room who believes in ways entirely opposite. In this situation the participant must find a way to hold on to his own beliefs while at the same time loving and respecting his dialogue partner, realizing that the other person also holds his beliefs to be true. We are not simply talking about the abstract doctrines of belief; we are talking about real issues--how you raise your children, whether or not your parents are "saved," whether or not your beliefs will help end suffering in your community, etc.

The process is not easy. It is further complicated by the fact that the participants are people whose profession it is to proclaim their message as true, people who feel they have been called by God to bring all people to the "truth." Imagine what it must be like for them to encounter these kinds of challenges! Imagine the kind of activity that is going on within people's hearts and minds at conferences like these! The CWR sets up conditions in which each person's beliefs are given full and fair expression. Everyone is to be treated with respect and dignity. What the religious leaders learn in these unique environments is what they bring back to their own followers.

In essence, I believe Father's vision is ultimately to see the cooperative network of the people whose words have the greatest impact on the religious world -- the people through whom the authoritative word of each religion is given -- such as the Pope, the chief Rabbi at the Jewish Theological Seminary, or the Sheikh of Al Hazar in Cairo. These are the people who must, in their unity, come to represent the reality of one world under God, and not just by words but by example. Their capacity for inter-religious cooperation will ultimately be the catalyst for making religion, or God, the true internal guiding force in the world. I think this is the kind of thing Father wants to see.

At

an intra-Buddhist conference in Chiang Mai, Thailand, Buddhists of

four different traditions converse. Left to right: Dr. Rabindra Bijay

Barua of Bangladesh, Dr. Hengching Shih of the Republic of China

(Taiwan), Dr. Chatsumarn Kabilsingh of Thailand, and Dr. Masao

Ichishima of Japan.

Question: How did the CWR actually begin?

John Maniatis, the director of IRF in 1984, had the task of setting the great vision for the Council in motion. His first step was to establish an international, inter-religious planning board. He did this by gleaning the extant IRF network for people from each major religion who might be interested. The primary qualification for participation on this board was that the individual must be a believing practitioner of the religion he or she was being asked to represent. The original planning board included rabbis, nuns, monks, and others.

By the time the board was established, I had been chosen as the founding director of CWR. Our first commission was to hold an intrareligious conference for each of the major world religions. [Infra means "within," as opposed to inter, meaning "between" or "among."] This reflects an important aspect of Father's insight into the matter of religious harmony.

Father recognizes that all the major religions of the world are divided within. There have been interfaith projects in this world for about 100 years, but rarely has anyone seen that it is virtually impossible to establish harmonious relations between religions as long as each religion is itself divided internally. Any proclamation of inter-religious unity made by one faction within a religion may well be ignored or denied by the believers of another faction of the same religion. That is why Father instructed the Council to proceed on two fronts simultaneously. The religions must achieve internal harmony and at the same time become one with the other religions of the world, sharing the desire for and commitment to peace on earth as a one-world family under God. Following this guidance, we organized five conferences in 1985--for Buddhists, Hindus, Christians, Jews, and Muslims, in that order. I flew westward from New York through Chiang Mai, Thailand; Pune, India; Frankfurt, West Germany; Weggis, Switzerland; and Istanbul, Turkey--arriving back in New York two months and five conferences later. That whirlwind 'round-the-world circuit was my initiation! The conveners of each conference were the members of our planning board. Each one broke the ice, so to speak, among the followers of his own religion.

Often the participants had to overcome a lot to get themselves to our conferences. But for the most part, once there, they instantly fell in love with the process. When people started dialoguing, the atmosphere became electric. We'd hear comments like: "This group is what I've been looking for all my life"; "I've wanted to do this since I was seven"; "I want my friends to experience this!"

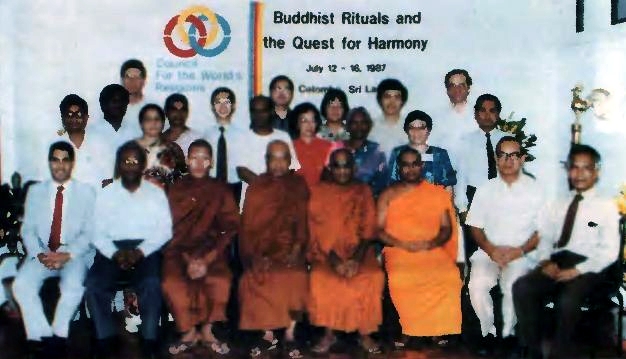

Group

photo at the intra-Buddhist conference in Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Question: How do your conferences differ from religious conferences put on by people outside our movement?

We are distinct from other religious conferences in ways that are very inspiring to our contacts. Ecumenical meetings can be dry, academic, and competitive. People do not go to them with the purpose of working toward the ability to say, "I can love and respect you"; rather they go there to say, "I am smarter than you, more correct, more insightful than you." This is unpleasant. It is an arena for egoism.

Some types of religious conferences are structured in such a way that the participants attend as "official representatives." In these situations the participants must be guarded and cannot speak freely, and one experiences mostly the posturing of others without any real heartistic exchange. People leave knowing that the real issues have been avoided.

There is a third kind of structure that is problematic for religious conferences; this occurs when one religion is the sponsor. The agenda is often subtly dominated by the biases and unrecognized presuppositions of the sponsoring religion. Representatives of the other religions who attend soon see that the possibility for dialogue from the position of equals is not possible under such circumstances.

Although the CWR is sponsored by one source, it does not suffer from the same pitfalls I just described. Participants at our and other IRF conferences feel equal to all other participants because of the way the planning process unfolds. One important task of the planning board, each member of which is an active believer in his own faith, is to insure that in each conference, every participant is listened to in a fair and open way.

Sant

Giani Naranjan Singh, the spiritual leader of several million Sikhs,

blesses Dr. Francis Clark, CWR senior consultant, at the Bad Nauheim

interfaith conference in 1986.

For example, during the planning process a Christian member of the board might present the idea of beginning the conference with the symbolic ringing of a bell, followed by a prayer. That sounds innocent enough, but then the Muslim on the board might say, "No, that absolutely will not do. One of the important things for Muslims is that only the human voice can be used as a call to prayer." These types of exchanges happen all the time, but because all the members on the planning board are committed to interfaith, there is never any acrimony or bitterness. We are all willing and grateful to be enlightened by our brothers and sisters from other traditions. For this reason, it is a quite a responsibility to be the representative of a religion on the board of the CWR. That person must be sure that the sensibilities of the followers of his own religion are observed. There is incredible effort given toward creating balance and harmony in bringing about the forward motion of the Council.

This cooperative action would not be possible were it not for Father's unusual degree of trust. I don't know of any person who would give so much support to a project while allowing so many other people to have a voice in the process. Sponsors of interfaith activities almost always have a specific agenda in mind.

Father, on the other hand, has only one desire: to see God's will be done. And he seems to trust the fact that, if these leaders from the world's religions gather together truly seeking unity, it will be an occasion for God to guide them according to His ideal. The board members respond to having so much trust placed in them by developing a deep sense of responsibility. They are proud to be the ones representing their religions, and they work extra hard to live up to the confidence that has been placed in them. The generosity and trust they experience coming from Father makes it easy for them to defend their choice to be involved with Father and the Unification movement. With this trusting spirit emanating from Father, a lot of the difficulties that plague other interfaith efforts are absent at our conferences. Our participants know they will never suddenly hear, "Okay, now you have to sign this statement of agreement," or something similar. It's really a free arena. The only purpose, really, is world peace through religious dialogue and harmony. People come and find that they can talk and that people are honest with each other. They discover real understanding and cooperation. It's never easy, but they begin to believe for the first time, "It's possible."