![]()

The Words of the Townsend Family

|

|

The Words of the Townsend Family |

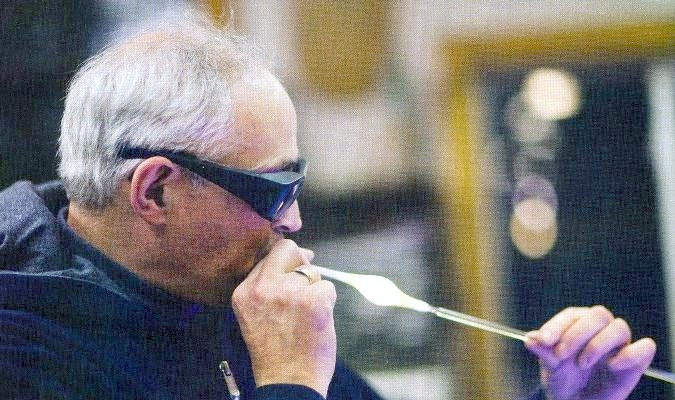

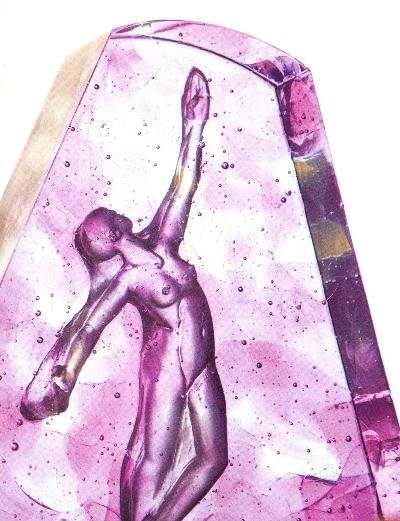

Milon Townsend is a glass work artist who lives in Hilton, New York with his wife and son. His home is also the location of his studio, in which he works 12 to 14 hours each day seven days a week, with a small team of other skilled glass artists. His style is greatly inspired by the world of dance, which is evident in his designs, strongly capturing motion and gesture. Mr. Townsend is a self-taught artist and has been working full time in glass artwork for over 40 years with techniques such as casting, slumping, fusing, cold working and flame working. He has made over a million pieces and has developed some of his own techniques and collaborates with other artists with his innovative coloring and casting techniques. He sells his work at festivals, markets, galleries and online and also teaches classes at the Corning Museum of Glass. As an educator and contributor to his field, he has written about nine books, 200 articles, and created 14 DVDs. He has made about one million pieces of all sizes and various forms, one of the most recent being a memorial piece for the city of Binghamton, New York.

Question: Is there a particular place or artist you look to for inspiration?

Back in the '80s when in New York City, in Greenwich Village, I did a lot of work with the ballet community in Manhattan. I was very interested in the human form and motion; the lines are very clean and pure in ballet -- it's very beautiful to me. I read about and looked at the works of Rodin and Michelangelo. Those two artists are the best examples of people in history who worked with the human form, and they inspire me. Articulation and movement, gestural figures -- that's what I find interesting.

I'm also interested in natural forms. I like nature. Right now I'm doing castings. I have a wooden fence post which shows all the grain in the wood. I take that from nature. I work with water forms, I work with fish forms. A lot of my fish are cast from actual fish. So I like working with natural forms. I also like fantasy forms. I like the dragon. I've been doing dragons for 40 years and to me, it's sort of a purely decorative form because you have color, you have line, you have form. Nobody can tell you that your dragon is not "correct," can they? So it's a great image to work with. I really enjoy the dragon.

In terms of mythical significance, man is the meaning-making creature -- Unification Thought, right? And in the Western culture dragons are connected with the devil and evil and Satan. In the Eastern culture it's the opposite of that: Dragons are holy. So which is the dragon? You get to pick. When it comes to art, the audience is a co-creator; they take different things from the piece. But for me, the dragon is purely an artistic, aesthetic expression of line, color and form.

Question: When approaching work. You want to add your own original touch to it and keep it interesting as opposed to making many identical pieces for a show, for example. Do you prefer working on single, more original pieces?

I was trained as a musician, and making a new, one-of-a-kind, massive sculpture that you'll never make again is like composing a symphony. Making a little mermaid that I can make in seven minutes is like being a street performer singing a song -- a seven- minute song, a three-minute song. Itzhak Perlman, the violinist, even though he may play the same piece at every concert he goes to, he puts his whole heart and soul into it every single time he does it. That's how I look at it. I do repetitive work sometimes -- I've made hundreds and thousands of the same piece at different times in my career, but even if I'm going to make the same piece again. I really want to make it the best that I can. There's an element which I refer to as creative dissatisfaction; after you've made the same piece ten times, you really want to do something a little bit different. So you'll tweak it. You'll say, "What if I do this? What if I do that?" And you'll see the design change, evolve, grow and hopefully improve.

Question: How do you color your glass? What are some of the techniques for this?

I've been in this game for 40 years, and when I started there really wasn't any colored glass. I had to mix the oxides myself into the glass. Copper oxide makes red, cobalt makes blue, tin and zinc make white, manganese can make black -- they are rare earths or heavy metals -- cadmium makes a beautiful red, orange and yellow, but it's toxic. So these chemicals get mixed with the glass and temperature, which I used to do, but now companies are producing it. I know all these people who started these companies, and I will often help them develop their colors. That's one of the nice things of being one of the old men in the field -- it's a small community and we all know each other. It's a good time to be in this field. There are a lot of exciting, new things happening, especially with color and technique and raw materials that are available to us to work with.

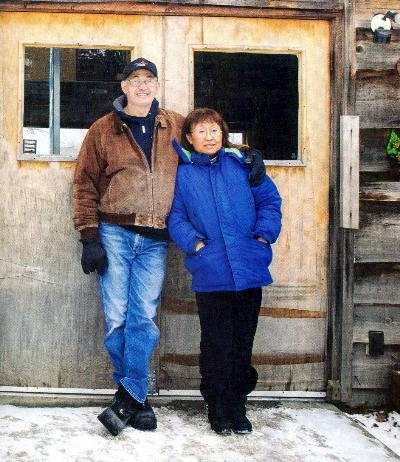

Milon

Townsend and his wife, Kiyoko in front of his studio in Hilton, New

York

Question: What are the different techniques and mediums you work with?

I do glass flame working, which is creating objects under torch one at a time. I do glass casting, the lost wax process, which can be used to make bronzes but I use to make glass sculptures with. And the original artwork there can be made in clay or glass or anything but is cast in glass ultimately. I do something called reverse relief casting where an image is in the back of glass and is illuminated so you can see the reverse relief image in it. We also do something called cold working where the glass is grounded, polished, and faceted so that it reflects, refracts and gives you many different effects. Cold working is mostly used as an adjunct to other kinds of work, to finish work or to make work look complete.

Question: Could you describe some of the techniques you developed?

We have a torso here; see this pattern around the outside of it? It's an organic pattern. Every time I make this, the torso could be the same, but this pattern is going to be unique every time. The way this pattern is created is something I call ceromancy. "Cer" means "wax," and "sincere" means ''without wax." Did you know that? When they made a sculpture and they broke something off, they'd stick it back on with wax. So a sincere piece is one that was complete and entire without something being stuck back together. So that's where the word "sincere" comes from. Ceromancy is the oldest known form of divination in which someone would go to an oracle, ask a question, pour hot wax into a dish of cold water -- which creates a very intricate and interesting pattern -- and then the oracle would interpret it. This is a technique that I developed which is comprised of taking a wax or a glass object, floating it face-down in a vessel of water, and pouring hot wax in the back of it. The wax spills over the side of it to create these patterns. So this is not like a torso stuck on this background, but the background is derivative of the shape around which the wax flowed. That's something I developed. I'm very excited about this. This could be the single most important innovation and development in my work in five years. I'm very hopeful about it.

Question: How do you organize your time as an artist?

I work seven days a week, and 12-14 hours a day. There are few artists that make their living from doing their work full-time. Many teach, have another job or have their spouse who has a regular job for their income. Few and far between are we who support ourselves solely on the output of what we do. My team and I make very small things such as earrings that sell for $15 to $40. We make installations that sell between $40.000 and $80,000 that weigh over a ton, and we do everything in between. I like that because I never get bored; I never do the same thing all the time.

In our year we have cycles. I just finished teaching at the Corning Museum of Glass -- I do that every year in January. In February we have a wholesale show where we take orders on wholesale items we make. In March we have a flame working conference. In April, I teach a class in Las Vegas. In June we have a pig roast. In July, August, September and October we do Renaissance festivals. In November, I do work for a catalog and in December we have a studio sale. We have these patterns in our year and each of them requires something different from us.

I also write books and make videos. I'm an educator. This year is a book year for me -- I'm trying to get three books out this year, which is nuts but that's what I'm trying to do.

Question: What techniques and mediums could a student in one of your classes expect to work with?

For one, what I work in the torch is called borosilicate glass -- a high temperature-resistant glass developed for the laboratory. However, it's been used for years now to make pipes with for smoking pot; there's a huge community of young men and women in this country who make bongs and pipes and things like that to smoke with. They have incredible skill sets in making hollow-formed work, and a lot of new colors and tubing have been developed for them to make those with. I have access to all those new and exciting techniques, but also I wrote a little book called Making a Living without Making Pipes for all these young men and women to see that there's another way should they choose to take it. Every time I teach a class on this, my students have to have some previous experience, and we would have something called "the talk." They sit down with me and they say, "Milon, I want to stop making pipes and make art." And it isn't that simple of course. I've been trying to make art for 40 years and sometimes I come up with a good piece, but a lot of the time it's not so successful. We have to have this conversation and help them understand what the work is really about: it's not about "pipes" and "not pipes," it's about art and craft. It's about taking these incredible skills and applying them to something meaningful. I'm grateful to be in a position where I can speak to these kinds of people and they'll listen. The people who have done what I suggested they do have done quite well.

Question: Can you describe your experience and approach as a teacher?

I teach for one week each year at the Corning Museum of Glass and I always experiment in my classes. Partly that's so that I can learn, partly it's so that students can see how I learn. How do you explore? How do you develop? What do you do when something doesn't work out?

Part of the process of developing your work is getting past what you would call a failure. Thomas Edison said, "I've had many temporary setbacks, but I've never had a failure." Failure is when you stop; you don't fail until you quit.

My classes are so exciting for me and for the students because we are trying lots of new things. I don't ever really try to teach the same class twice. I don't want to go through the same things over and over. That's why I don't want to teach at a university, college or high school where I have to teach the same things year in and year out. I really like teaching for a very intense week-long class, trying new things each time.

Question: What advice would you give to someone interested in making art with glass?

Whatever art form you practice, do it every day. Even if it's just a little bit. That's how you will develop much more momentum and consistency and a higher skill set -- if you do it every day. So there's the secret: continuous application of the seat of the pants to a chair; sit there and do it and do it and do it, and don't stop doing it. That's the secret. Some people say to me, "Yeah, I tried that once." That's the problem, you tried that once. So whatever it is that you're interested in doing -- doesn't matter if its glass or anything else -- you really have to keep on doing it for a long, long time, every single day.