![]()

Ten Theologians Respond to the Unification Church - Edited by Herbert Richardson 1981

|

|

Ten Theologians Respond to the Unification Church - Edited by Herbert Richardson 1981 |

In The Symbolism of Evil Paul Ricoeur remarks that the "primitive naiveté" which issues from the "immediacy of belief" has been "irremediably lost." The immediacy of belief associated with the first naiveté is no longer accessible to moderns who have passed through the critical furnaces of demystification and demythologization. Faith is accessible to us only through interpretation of past texts and traditions. This accounts for the ascendancy of hermeneutics in the sacred sciences. It is only in passing through the forge of critical consciousness, Ricoeur claims, that we can approach a mediate faith and a "second naiveté."1

Yet there exists no general hermeneutic for the recovery of faith. Ricoeur detects two conflicting currents in modern hermeneutics. He encapsulates this conflict in the sentence: "Thus idols must die -- so that symbols may live."2 Ricoeur calls the first mode of hermeneutics the "hermeneutics of suspicion." It is dedicated to the reduction of the illusions and idols of false consciousness with which the human species is beset. The hermeneutics of suspicion is associated with the demystifying critiques of Marx, Nietzsche and Freud. By reducing the symbolism of religious representation to technical signs this troika of demystifiers sought to unmask religion as the opium of the people, the resentment of the masses, and as systematic illusion. The second mode of interpretation Ricoeur calls the "hermeneutics of the restoration of meaning." In this second mode there is the attempt to approach again the region of the Sacred through a phenomenology of symbol. This mode is identified with the interpretative work of Rudolph Otto, Gerhardus van de Leeuw and Mircea Eliade. Ricoeur's later work in hermeneutics is devoted to the mediation of the conflict in interpretations.

Besides the distinction between destructive and restorative hermeneutics, Ricoeur also distinguished between demystification and demythologization3 Demystification is the critique of religious representation arising from outside the domain of the sacred sciences, e.g., philosophy, economics, psychology. Demythologization is the critique of religion arising from within the sacred sciences themselves. Ricoeur's typology of the critique of the Sacred is in need of amplification and deepening. The hermeneutics of suspicion was a long time arriving.

The critique of naive consciousness and unproblematic faith is coterminous with the rise of modernity. Modernity has twin tap roots, one anchored in the Reformation and the other in modern experimental science. It is imperative to recollect the steps dong the route to the hermeneutics of suspicion.

From De-allegorization to Demythologization

De-allegorization, The Reformation commences with the reduction of the medieval fourfold sense of scripture (the literal, the allegorical, the moral and the anagogical) to the literal, i.e., the historical, sense. The power of medieval exegesis was its ability to provide symbols of immediacy by which human existence would be imagined and life could be lived. Nowhere do we discover this power more fully expressed than in the medieval cathedral. Emile Male has described medieval art as a scriptural art.4 The building blocks of the medieval cathedral were not stones and beams but the typologies and allegories derived from scripture and tradition. The medieval cathedral was a symbolic calculus for the interpretatio naturx et historic within the universal themes of Creation, Fall, Redemption and Last Judgment.

The virtue of medieval exegesis, however, conceded a vice. The web of typologies and allegorizations would both surpass and pass by the plainness and directness of the primary meaning, the literal sense, in a cloud of false explications and rationalizations. The weakness to which allegory was prone was the conviction that the true meaning, the hidden philosophical meaning, lay either behind or above the literal sense. Thus the letter was understood to be a false disguise of the spiritual sense intended to deceive the uninitiated. We can see this type of allegorization, for example, in Philo Judasus' transposition of the story of the Fall in Neo-Platonic psychology: Adam = terrestrial mind; Eve = sensation; Serpent = pleasure. Whatever else may be said about this speculative transposition, it de-texturizes the story itself and detours around the fundamental ambiguity of the two accounts of creation: the paradox of finding oneself having been created good yet inclined toward evil. In reality, the allegory dislocates the authentic paradox and replaces it with a false one: a "good" spirit housed in an "evil" body.

The obscurantizations of medieval allegory motivated the reformational "return to the Letter" and the establishment of the principle that scripture interprets itself {scriptura sux ipsius interpres). There may be obscure passages in scripture, Luther argued, but the obscurity is due to our own linguistic and grammatical ignorance and not to any obscurity in the content of scripture itself.5 Whatever had been concealed in former times was now revealed in Christ. Rather than resorting to such allegorical handbooks as Dionysius Areopagiticus' Ecclesiastica Uierarchia or Gulielmus Durandus Rationale Divinorum Officum, Luther recommends consulting other places in scripture where the meaning is plain and dear.

While avoiding the danger of phantasmagoric allegorization, the Protestant principle of scriptural interpretation ran other risks. What was one to think when the literal sense itself was symbolic and ambiguous? Then, too, christological exegesis is something more than a "literal" reading of the text and had the tendency to collapse the meaning of the Old Testament into the New in a Law/Gospel dialectic. And the stress on the "plain style" of interpretation opened the path to the banal moralization of the text, such as the Puritan sermonizing of The Parable of the Sower in order to get the congregation to plant more potatoes for a bigger harvest.6 Finally, the principle that scriptura suae ipsius interpres carried with it the implication that scripture was no longer sufficient for the interpretation of the Books of Nature and History but simply rebounded back onto itself.

De-idolization, Luther's de-allegorization of scripture was soon to be accompanied by Bacon's de-idolization of the Book of Nature, Bacon names the idols as those of the Tribe (human nature), the Cave (individual perception), the Market Place (language) and the Theatre (ancient philosophy which emphasized contemplation over action).7 As Luther sought to sweep away the allegories which obscure the plain sense of scripture, so Bacon sought to smash the idols which impede mankind from re-assuming "empire over nature." The principle of the "return to the letter" dovetails neatly with the Baconian principle of the "return to things themselves" (ipsissimx res).8 The vacuum created by the principle that nature interprets itself paved the way for the principle that natura sua: ipsius interpres. With a mixture of boldness and caution Bacon ranked the Book of Nature ("the book of God's works") on a par with the Book of Scripture as a kind of "second Scripture."9

The parallel between Luther and Bacon, however, needs to be qualified. For Luther the Fall meant the corruption of mankind by sin. For Bacon it meant the loss of knowledge and power. Like the modem thinkers who followed him, Bacon underestimated the effects of the Fall and believed that mankind could refurbish the image of God by wresting power from nature through the applied arts. Bacon stands at the midway point in the great hermeneutical reversal of modernity. The new "active science" was to overfill the vacuum left by the principle that scripture interprets itself. Henceforth the interpretation of nature became the criterion for the interpretation of scripture, This is reflected in Spinoza's statement that "the method of interpreting Scripture does not differ widely from the method of interpreting nature -- in fact, it is almost the same,"10 Under the demystifying gaze of modern "higher criticism," myth was separated from history, miracles from the laws of nature, and symbolic language from the description of "reality." This led to the second wave of modernity, the disenchantment of the world.

Disenchantment. The phrase die Entzauberung der Well was made famous by Max Weber and popularized by Harvey Cox in Trie Secular City. Weber took the phrase from Friedrich Schiller.11 The word Entzauberung can be translated as "demagification" or "desorcerization" as well as "disenchantment." In the enchanted universe there existed a reality apart from human interest. The world was represented as a "living cosmion" which provided consciousness with symbolic links between the rhythms of nature and human existence. This living cosmion vanished with the rise of modern science which deciphered nature into a system of calculable forces. The forces could be manipulated and transformed to human purposes. In Bacon's words, nature could be put "under constraint and vexed... forced out of her natural course, and squeezed and molded."12 Thus the living cosmion was disenchanted. In its place was the mechanical cosmos in which nature was reduced to "object." Even the human body, as Hegel was to notice later, appeared in the form of an animated tool.

In disenchantment the world lost its narrativity The Baconian interpretation naturat reduced the natural order to an array of "instances" which could be codified and turned into a means of production. The new active science dispelled the world of numina along with such lesser genii as sprites, elves and goblins, but it also took away those sensuous symbolic links whereby human existence could be bonded to the being of the world. This was the beginning of the "fact/value" distinction and that peculiar affliction of late modernity which elsewhere I have called "inner-worldly gnosticism."13 In the "other-worldly gnosticism" known to the historians of early Christianity, Creation, especially the material creation, was seen as the bungled handiwork of a malevolent Demiurge. The aim of salvation through gnosis was to escape the homelessness of time and the rootlessness of space by a leap into the everlasting abode of the "true Self." In inner-worldly gnosticism there are no cosmic exits and "nature" is not the handiwork of a Demiurge but an accidental conglomeration of matter which is indifferent to human purpose. Nature is not so much evil as "neutral," The "facts" of objective reality are "indifferent" to the "values" the subject arbitrarily bestows upon them. "Facts" are beyond good and evil; they are "value-free." In the disenchanted universe the "facts" no longer present dues for the imaginative representation of existence as story but offer instead ciphers of power for the mastery of human and non-human existence.

Demythiftcation and Demystification. The paradox lying beneath the disenchantment of the world was that, as moderns took ever greater "dominion" over the earth, the physical world became objectivized, factualized and rationalized, The meaning, purpose and finality of the whole evaporated as human "goals" and "values" loomed larger. The humanization of the world, according to the thinkers of late modernity, meant also its rationalization, With the Hegelian and Marxist projects of demythification and demystification, the hermeneutics of suspicion was broadened to include the hermeneutic of history or, perhaps more accurately, the broadening of suspicion implied that history itself was the hermeneutic.

For Hegel, mythical consciousness is alienated consciousness. The rational concept first dwells in the "limitless wealth of forms, appearances and configurations" of the variegated rind of myth.14 In order for the Geist (which is neither the pneuma of the New Testament writers, nor the psyche of the Greek philosophers, but "subject") to become at home with itself, to become consciousness which is both in itself and for itself, it must shuck off, peel away, and enucleate [enthullen] once-for all the mystical rind. The alienation engendered by mythical consciousness is overcome only through rational historical action. Nature as alien object is overcome through work, which, in turn, leads to the overcoming of the Master-Slave alienation and to political emancipation. Finally, the divine-human alienation (god as Stranger or Other) is overcome through the acquisition of immanent absolute knowledge. Hegel saw the historical process as one of progressive rationalization and secularization. The Protestant principle, for example, represented both the Christianization of the sxculum and the secularization of Christianity15 The transition from the alienation of mythical consciousness to reconciled consciousness is refracted in the transition from classical epic (the hero) to the novel (the bourgeois worker) and from poetry to prose.16 The modern representation of the world is a prosaic representation.

Marx advances upon Hegel's critique of mythical consciousness on two fronts. First, Marx claims that the material conditions of existence are not the expression of the Idea but quite the reverse. The Idea, particularly the idea clothed in religious representation, is often a veil masking the intolerable conditions of alienation. Marx subsumes the critique of religious representation under ideology critique. Religious suffering, for example, is the "expression of real suffering," but religion also serves as "the opium of the people."17 The authentic religious sigh becomes deflected and mystified when the protest of the afflicted is transposed into an imaginary "Heaven" where all wrongs will be righted. Secondly, Marx's critique of "holy" illusions lays the groundwork for the critique of the "unholy" or secular illusions in law, politics and economics. For example, Marx exposed the 19th Century monetary system as a fetishistic pseudo-religion in which money functioned as an "actual god" by which human relationships were reduced to a material commodity relationship.18

In the Republic Plato subjected myth and poetry to the critique of the logos. The Platonic critique, however, was not aimed at the abrogation of mythic consciousness but only at its purgation (katharsis). Demythiftcation and demystification, by contrast, have as their intended purpose the annulment of myth and symbol in the pursuit of rational consciousness. Though Hegel and Marx stripped religious representation of its ideological links with the structures of alienation, domination and submission, the future held in store only greater bureaucratization and rationalization of life and world.

Disillusionment and Decipherment. By historical reckoning disillusionment and decipherment follow demythiftcation and demystification. Structurally speaking, they relate to disenchantment. The disenchantment of the world as object was the prelude to the disenchantment of the world as subject. The fortress of the Ego, initially so confident of its inwardness in faith (Luther) and its certainty in doubt (Descartes), succumbed to the distressing critiques of Nietzsche and Freud.

In Nietzsche's critique of religious representation, the hermeneutics of suspicion attains its full destructive force. Nietzsche unmasks the religious motive as the revenge of the weak against the strong, the apotheosis of lower herd instincts (Christianity as Platonism for the masses) and the resentment against the becomingness of the world.19 For Nietzsche, all gods ("ideals") have no ontological connection with the world but issue from human evaluation; all evaluations come from self-overcoming and dl self-overcoming is reducible to the will-to power. In particular, Nietzsche unveils Christianity as the devaluation of the noble religion of the strong (the Greeks) and the creator of world-negating values which vitiate the affirmation of natural life "by inventing another world."20 Where Marx stood for a critique of religious consciousness from the left, Nietzsche stands for the critique from the right.

Nietzsche uncovered the naked "self" and Freud proceeded to dismantle that "self" from within in his decipherment of the psychic life into an economy of drives (Unconscious, Conscious, Preconscious) or, later, into a topography of competing domains (Id, Ego, Superego). The apparent autonomy of the conscious Ego was dethroned, and the decipherment of dreams uncovered an infinitude of desire attached to the indestructible narcissism of the child's wish for fulfillment. Freud's critique of religious representation is introduced in the context of infantile wish-fulfillment. Religion is systematic illusion (Freud distinguished illusion from both delusion and error) which never rises above the imperialism of the infantile wish. Naive religion is, for Freud, religion proper and any softening of the primal guilt associated with the timeless murder of the primordial father with notions of Providence or "oceanic feeling" of oneness with the universe is but secondary distortion and illusion.21 The analysis of religious imagery suffers the same fate as the analysis of dream imagery.

Demythologization. Demythologization represents the critique of religious representation from within the sphere of faith itself. Given the destructiveness of the hermeneutics of suspicion, demythologization is the attempt to recover a critical faith in post-modernity. It rests on the twin foundations of Barth's critical theology and Bultmann's demythologizing hermeneutic, With these two enterprises there is a recognition that one cannot return to the first naiveté of religious representation.

According to Barth, critical faith arises when fallen humanity encounters the KRISIS of God in the proclamation of the Gospel (kerygma). The KRISIS is dialectical: a "No" to the old Adam and human achievement and a "Yes" to the new humanity bestowed by God in Christ. Following Kierkegaard, Barth distinguishes radically between faith and religion. Faith is the encounter with God as wholly other, It is in no way grounded on our experience or capacity to represent the divine. Religion, on the other hand, is "the supreme possibility of dl human possibilities."22 As such, it can fall into the idolatry to which all human institutions are prone. Critical faith unmasks religion as a narcotic. Critical faith, or, better, faith under KRISIS, is not a tangible reality within human grasp but faith in faith itself.

Bultmann's demythologization builds upon Barth's notion of critical faith. As Hegel and Marx sought to extract the rational kernel from the mythical rind of consciousness, so Bultmann seeks to extricate the nucleus of faith -- the kerygmatic event of the Word of God addressed to each person in his or her existential depth -- from the mythological representation in which it was originally embedded. Demythologization is not an accommodation of the scriptures to the scientific presuppositions of modern consciousness, Rather, it is the attempt to enudeate the authentic skandalon of the biblical Summons to modems in spite of their adherence to a modem scientific world view.23 Through demythologization the cultural vehicle of mythological language in which the kerygma was first embedded is revealed as a false scandal. The red stumbling block, according to Bultmann, is the word of the cross.

The path which has led from de-allegorization to demythologization has, I believe, irretrievably removed the function of religious language as scientific explication. The symbols and myths (or stories) through which religious discourse achieves its aims can only appear as a science-manqué' from the perspective of a modem scientific world view. However, this destructive consequence has a restorative side. If religious discourse is not science-minus, then perhaps it is poetry-plus. Pad Tillich has suggested that Bultmann's project of demythologization ought to be called deliteralization for it recovers for us the function of religious languages as symbolic representation.24

Sign vs. Symbol. Scientific discourse operates through the use of signs which are fixed in intentions, transparent in meaning and stable throughout argumentation, Signs allow for the organization of a field of experience of what Kant calls the schematism. In logical discourse equivocation in the use of the sign would be intolerable. Yet in order to achieve their purpose, signs must abstract from the existential thickness of existence. Symbols proceed along a different route. Symbols arise when a primary meaning ("the letter") gives rise to another meaning ("the spirit") which is yet bound to the first. Thus symbols are equivocal. Ricoeur and Victor Turner have discussed how symbols have double meanings which link sensuousness with normativity and the rich texture of existence with ultimate meaning.25 The equivocation of symbols, however, does not arise through a default of religious discourse but through the surplus of meaning which symbols embody Symbolic discourse says more than can be said in logical discourse.

The double-vector quality of symbols, however, necessitates a hermeneutic of suspicion. Between the primary and secondary meaning there can emerge all sorts of distortions and falsifications. From this perspective, symbolic discourse is in need of logical discourse which "dis-implicates" the primary symbolism from false secondary elaborations. But this takes place in and through symbolic discourse itself. Here the example of Second Isaiah is instructive. In the complex and rich language of this prophet we encounter both the extreme of iconoclasm and destruction of false idols.(Is. 44:1 ff.) and yet the recrudescence of mythic symbols of Creation and Exodus interwoven with inverted myths of the Ancient Near East, vignettes from everyday life and historical events surrounding the reign of Cyrus, But, it should be pointed out, in Second Isaiah the very moment of the destruction of false idols of consciousness (religious symbols which have sedimentized into graspable idols of the Wholly Other) is also the moment of resymbolization. In the critical consciousness of modernity, on the other hand, the reduction of meaning to the transparency of the technical sign has created a crisis in symbolization.

The Technical Sign. Modernity has terminated in what many have called the technological society. By technology I mean the techne (art, craft, making, doing) and logos (word, reason, rationale, knowing).26 Though the term is derived from the Greek, it is important to point out that the ancient Greeks would have never joined these two words, i.e., they never would have placed knowing on the same level with doing. The word "technology" is a neologism which arose sometime early in the 17th Century. There is no doubt that technology has given modems great mastery over both non-human and human nature. Yet the very mastery over our external and internal environment has generated a crisis in symbolization. Why is this so?

The very power of technological mastery conceals a darkness. The technical sign, to which all has been reduced, homogenizes the heterogenous. Within this homogenization humans are constrained to envision their lives in terms of inflation rates, statistical averages, economic projections, etc. The very transparency of the modes of measurement demands that people abstract from the very texture of their existence. Secondly, the technical sign is totalizing. Nothing is immune from its analytic mastery -- religion, art, sexuality etc. Thirdly, the technical sign rationalizes existence, i.e., it tends to reduce everything to a means-ends criterion of efficiency. In Toward a Rational Society Jurgen Habermas has argued that technology possesses a "glassy background ideology"27 which tends to dose down the transmission of meaning (the hermeneutical function). Technical signs facilitate the making of "decisions" but they do not necessarily engender "meaning," which is carried by communities of people who are in dialogue with one another. The technical sign is "monologic."

Recovery of Symbol. This is the point where I see the new religious movements entering in. I believe that one of the unrecognized aspects of new religious movements is their recovery of life as story, and in order to tell that story one needs recourse to symbols. The very ascendancy of the technical sign has meant that human existence has taken on a metonymic thinness and prosaic meaninglessness, The new religious movements represent not simply the search for the Sacred but also the quest for metaphoric richness by which the story of life can be symbolized and lived out. Furthermore, the recovery of symbol takes place within the context of communities. The technological society thrives best on the isolated individual -- the narcissistic "consumer" -- and the aloof, abstract corporate bureaucracy. It is no wonder that technological mastery has wreaked havoc on the intermediate institutions such as family, church, voluntary associations, etc. Thus the search for symbol is identical with the search for community, for the community is the proper locus of symbolic dialogue about the meaning of life and death.

The very success of the technical sign has produced a crisis in symbolization. Although computers can do marvelous things, they cannot tell stories about human life. All they can do is process information and information is constituted by endless seriality. Information has no beginning, no middle and no end. In order to tell the story of life, one needs symbols which unite the concrete sensuousness and relatedness of existence with images of a universal destiny. Ina curious way, our situation parallels that of the Roman Empire in the First Century A.D. As the empire dosed back on itself and sought to manage the population, a kind of meaninglessness set in. It was at this time that we find the spread of the new religious movements -- the mystery religions, Mithraism, the cult of Isis, dong with Judaism and Christianity. I think one of the principal reasons for the phenomenal spread of Christianity is that it had concrete stories to tell, stories like those about Adam and Eve, Abraham, Moses, David and Jonah. Through these symbolic stories people could find the mirrors of their own lives. The concrete stories were bound up with the universal themes of the Creation, the Fall, the Redemption and the Last Judgment. Something similar, I suggest, is happening in the new religious movements.

Facts, data sheets, economic projections, etc., are not the mate-rid with which human life can be symbolized. They may be a part of existence in the modern world, but they cannot give life a meaning. Ultimate and sacred symbols are not just frosting on the cake. Yet the unspoken imperative of the technological society is for us to disenchant ourselves of our visions of the Good, to de-idolize the past, to decode and decipher our dreams into neurological forces, to disillusion ourselves of the religious dimension, to demystify the process of society and even to demythologize our sacred books. I do not think that we moderns can escape the consequences of the hermeneutics of suspicion. At the same time, none of us should be surprised that from within the ascesis of meaning in which modernity has terminated, the phoenix of the symbol rises from the ashes. It is in times like these that some perceive that the symbols of the Sacred, illusion though they be, are still necessary illusions. The recovery of symbol in the new religious movements represents a search for what Ricoeur calls the "second naiveté" or "the post critical equivalent of the precritical hierophany."28

If I apply some of these thoughts to Unification theology, I would say first and foremost that Divine Principle reconstitutes the symbolic narrativity of the messianic story. This narrativity is not simply a succession of events attached arbitrarily to a series of dates but a pattern or plot -- or what Aristotle calls a mythos (Poetics 3450a 3-7) -- which has a beginning, a middle, and an end. The parts of a plot are not related to one another episodically, i.e., on a foundation of mechanical seriality. Aristotle calls the plot the "soul" of the story whereby the beginning, the middles and the end are related by way of repetition and inversion. One can read the end in the beginning and the beginning in the end. In an earlier essay I compared Divine Principle to Milton's Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained.29 Both works might be called theological epics. They do in words what the medieval cathedral did in stone by encompassing the story of Creation, Redemption and Glorification (Restoration) within a symbolic whole.

Divine Principle claims to have uncovered the mythos of Heilsgeschichte by uncovering the original purpose of Creation (Divine Principle, pp, 41-46). From the structural aspect of the plot, the Fall of humanity constitutes a deflection from the original purpose of Creation. The thematic motive of history -- in Aristotle's term, the dianoia -- is the restoration of the original principle of Creation which is defined as the Kingdom of God on Earth. The path to restoration is marked by repeated attempts by "central figures" and repeated failures (Divine Principle p. 56). The understanding of history in Divine Principle is neither linear nor cyclic. Rather history happens on the model of a gyre or spirit with greater and greater intensification in messianic expectation. Thus it would be erroneous, I believe, to interpret the "central figures" and "periods of time-identity" (Divine Principle, pp. 45-47) as flat cyclic repetitions on the model of the Greek kykloi or the Hindu jugas. Rather, Divine Principle unfolds the messianic story in a way that used to be called typological, Today typological exegesis has gone out of fashion but in former times typology was the mode whereby the greatest minds discovered the truth and unity of the Bible and the coincidence between the truth of the Bible and the truths of nature and history. Figures and types -- today we would say symbols -- were routes to the truth. "The type," wrote Pascal, "is made according to the truth; and the truth is recognized according to the type."30 Thus Adam is a type for Christ (the antitype of which the type is the foreshadowing).

An innovation in Divine Principle is that it reads the type-antitype formula both forwards and backwards. Adam is not only a foreshadowing of the Christ. The Christ is also a recapitulation of the original Adam (and Eve). Thus Unification Christology is modified by its "Adam/Eve-ology." Furthermore Christology and "Adam/Eve-ology" both articulate and are articulated by Divine Principle's Adventology, i.e. the teachings pertaining to the Lord of the Second Advent, the restored Family and the True Parents. In this way the teaching about the beginning (the original Ideal Family) and about the end (the True Parents) modify Unificationist Christology. The Christ's mission was to restore the broken relationship between man and woman and humans and God by taking a Bride and raising children in a God-centered family. From this aspect, the mission of Jesus was incomplete. Certain Christian critics of Unification theology object that, since Divine Principle teaches that Jesus failed in his mission, Unification "cannot be regarded as Christian,"31 Against this objection, two things may be said. First, Divine Principle does not precisely say that Jesus failed but, rather, that the will of God for the full spiritual and physical restoration of humanity was failed by the disbelief of the people in Jesus (Divine Principle, p. 196). Second, Divine Principle claims that Jesus and the Holy Spirit did fulfill their mission of "spiritual True Parents" (Divine Principle p. 217). It remains the role of the Lord of the Second Advent and his Bride to bring the physical restoration in line with the spiritual restoration already fulfilled by Jesus and the Holy Spirit,

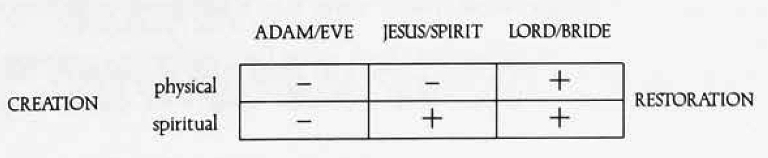

These criticisms of Unification theology, however, come from a viewpoint that places priority on doctrine whereas the deep structure of Divine Principle reveals a typological mythos or symbolic narrative. Before Unification is put through the acid bath of conventional orthodoxy, I think it is incumbent upon the critic to recognize the fundamental symbolic structure of Divine Principle. Doctrinally speaking, Unificationism is a two-article theology (Creation/Restoration).32 This doctrine, however, is encoded in the symbolic narrative about the coming of the Messiah. Originally, Adam and Eve were to be, so to speak, their own messiahs. In the Fall they disrupted the process of the three Blessings both on the physical and spiritual levels. Through Jesus and the Holy Spirit the spiritual dimension was restored but not the physical. Finally, the full restoration is brought about by the Lord of the Second Advent and his Bride. The bare bones of this symbolic structure can be diagrammed thus:

Whatever else may be said about Divine Principle, I think that, as a typological mythos for post-modernity, it presents a consistent and motivating symbolic structure for the adherents of the Unification Church. Many researchers into Unificationism overlook the symbolic and narrative dimension to conversion to the movement. Most believers will tell you that they were first convinced of the truth of Unification after hearing the Fall of Man lecture based on Divine Principle. In other words, many have come to a second naiveté in, through and by a story that claims to uncover the fundamental human predicament and holds forth a solution for the restoration of the world.

1 Paul Ricoeur, The Symbolism of Evil, trans. Emerson Buchanan ^Boston: Beacon, 1967), p. 351

2 Paul Ricoeur, Freud and Philosophy: Ah Essay on Interpretation, trans. Denis Savage (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970), p. 531

3 Paul Ricoeur, The Philosophy of Paul Ricoeur, ed. Charles E. Reagan and David Stewart (Boston: Beacon, 1978), pp. 213-22.

4 Emile Male, The Gothic Image: Religious Art in France of the Thirteenth Century, trans. Dora Nussey (New York: Harper, 1958). pp, 14-22.

5 Martin Luther, Bondage of the Will, in Marlin Luther: Selections from His Writings, ed., John Dillenberger (New York: Doubleday, 1961), p. 172 6 Perry Miller, ed., Introduction, Images or Shadows of Divine Things, by Jonathan Edwards, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1948), pp. 15ff.

7 Frances Bacon, The New Organon and Related Writings, ed. Fulton H. Anderson (Indianapolis: The Library of Liberal Arts, 1960), pp. 47-60.

8 Bacon, p. 114.

9 Bacon, p. 282

10 Benedict Spinoza, Thieologico-Polifical Treatise, trans. R. H. Elwes (New York: Dover, 1951). p. 90

11 Max Weber, "Science as a Vocation," in From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, ed. H.H. Gerth and C. Wrights Mills (New York: Oxford University Press, 1958), pp. 139 Ff

12 Bacon, p. 25.

13 Frank K. Flinn, "George Grant's Critique of Technological Liberalism" (Diss. Univ. of St. Michael's College, Toronto, 1981), pp. 268 ff.

14 G.E.W. Hegel, Preface, The Philosophy of Right, in The Philosophy of Hegel, ed. Carl J. Friedrich (New York: Modern Library, 1954), p, 225.

15 G.E.W. Hegel, The Philosophy of History, trans. J. Sibree (New York: Dover, 1956), pp. 542-46

16 G.E.W. Hegel, Aesthetik in Hegels Sdmmtliche Werke, ed. H, Glockner (Stuttgart: E Frommann, 1927-41), III, 341, 395.

17 Karl Marx. Introduction, "Toward a Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Law," in Writings of the Young Marx on Philosophy and Society, ed. Lloyd D. Easton and Kurt H. Guddat (New York: Doubleday, 1967), pp. 250-251,

18 Marx, p. 266.

19 Cf. esp. Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future, trans. R.J. Hollingdale (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1973), pp. 56-71

20 Friedrich Nietzsche, The Antichrist, in Twilight of the Idols and The Antichrist, trans. R.J. Hollingdale (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969), p. 135.

21 Sigmund Freud, The Future of an Illusion, trans. James Strachey (New York: Norton, 1961), pp. 30-33

22 Karl Barth, The Epistle Jo the Romans, trans. Edwyn C. Hoskyns (London: Oxford Univ. Press, 1968), p. 241

23 Rudolph Bultmann, Jesus Christ and Mythology (New York: Scribner's, 1958), p. 36.

24 Paul Tillich, A History of Christian Thought, ed. Carl E. Braaten (New York: Touchstone, 1968). p. 524

25 ^Ricoeur, Freud and Philosophy, pp. 28-32; Victor Turner, The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Nalemfru Ritual (Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1967), pp. 27-29.

26 George E Grant, English-Speaking Justice, The Josiah Wood Lectures 1974 (Sackeville, New Brunswick: Mt. Allison Univ. Press, 1978), p. 88.

27 Jurgen Habermas, "Technology and Science as 'Ideology,'" in Toward A Rational Society: Student Protest, Science, and Politics, trans. Jeremy Shapiro (Boston: Beacon, 1971), p. 111

28 Ricoeur, The Symbolism of Evil, p. 352.

29 Frank K. Flinn "Christian Hermeneutics and Unification Theology," in A Time For Consideration: A Scholarly Appraisal of the Unification Church, ed. M. Darrol Bryant and Herbert W Richardson (New York: Mellen, 1978), pp. 153-56.

30 Blaise Pascal, Pensees (Paris: Editions Gallimard, 1936), p. 315.

31 A Critique of the Theology of the Unification Church As Set Forth in 'Divine Principle'" (National Council of the Churches of Christ, Faith and Order Commission, June, 1977). p. 5

32 Herbert Richardson, "A Lecture to Students at the Unification Theological Seminary in Barrytown, New York," in Bryant and Richardson, pp. 29-98.