![]()

The Family And The Unification Church Edited by Gene G. James

|

|

The Family And The Unification Church Edited by Gene G. James |

The late twentieth century has been described as an era of unprecedented family breakdown. Observers have cited the rising rates of divorce, illegitimacy, and extramarital sex -- a pattern that has been dubbed serial monogamy. Traditional roles of men and women have been challenged, and new, positive roles have been slow to replace them. Church attendance has fallen, along with the religious sanctions for traditional family values. The inevitable backlash has come in the form of the Moral Majority and the media evangelists appealing for a return to conservative Christianity and the nuclear family. Unfortunately, such prophets have offered a mishmash of platitudes rather than a coherent model for family life.

Christians face a real dilemma when it comes to the family. The Moral Majority notwithstanding, Christian theology has never granted a central role to the family. Roman Catholics may idealize the Holy Family, but a virgin mother, celibate foster father, and sinless son do not make a very helpful model for real family relationships. Protestants minimize the roles of Mary and the saints, but the result is an even weaker image of family -- the exclusively male lineage of Jesus and God the Father.

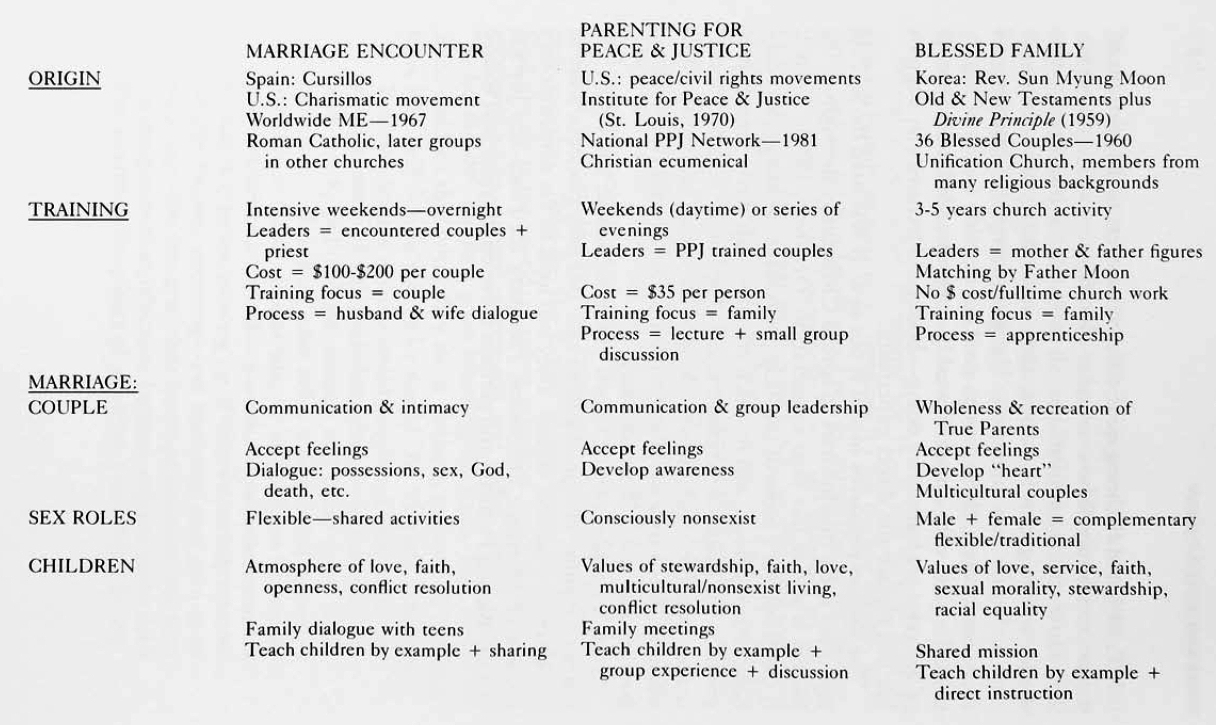

Christians who are seriously committed to marriage and the family are searching for new models -- practical, spiritual, human, supportive of women as well as men. Platitudes or distant ideals are not enough. To be of real use, a model must suggest a way of life for the family, articulated in some depth and detail. Such models do exist. Worldwide Marriage Encounter, the Parenting for Peace and Justice Network, and the Blessed Family in the Unification Church provide three different blueprints for family spirituality. All three are dedicated to human love within the home, family prayer, and social action in the world outside. It is not hard to see why these movements are attractive to families who have been looking for meaning and direction.

Worldwide Marriage Encounter has reached more than a million couples in less than fifteen years. Introduced to the U.S. in 1967, and popularized by the writings of Fr. Chuck Gallagher (1975), ME's roots include the Spanish Cursillos and the Catholic Charismatic Renewal. M E appeals, however, to a much broader spectrum of Catholics than its origins would suggest. It has also produced offspring in other denominations -- Episcopal (1971), United Church of Christ (1974), as well as Baptist, Methodist, Lutheran, and Seventh Day Adventist Encounters.

The ME message is spread during intensive weekends for couples held at retreat houses or motels. A donation of $100 or S200 per couple is typical, but the fees are voluntary; many ME couples donate child care for the weekend and double their contribution so that another couple can afford to attend. At a recent weekend in suburban St. Louis, most participants were twenty-five or thirty-five years old, ranging up to about sixty. There were factory workers, sales executives, homemakers, and doctors, along with a few academics and a few celibate clergy. Except for the clergy, everyone came in couples. Most people were active in their home parishes and often in the Pro-life and Charismatic movements as well.

M E sessions are led by a team of three encountered couples and a priest. Each team presentation is followed by a time for the couple to apply what they have learned through "dialoguing": husband and wife share their feelings in letters, which they then exchange, read, and discuss in private. Couples leave behind their televisions, telephones, watches, and the usual daily distractions. Yet time is highly structured -- ten minutes to write, then a bell, ten minutes to dialogue, another bell, then back to the conference room for another session. The entire focus is on the couple; group sessions involve no public sharing except by the presenting team. Even socializing around the snack table and walks around the neighborhood are frowned upon, so a husband and wife have no alternative but to spend the better part of the weekend encountering each other.

The presenting teams model good communication, showing the new couples how to express feelings honestly and openly. They read aloud samples from their own dialogue letters on such themes as fear, work, God, trust, sex, children, death. They provide slogans ("Feelings are neither right nor wrong"; "Love is a decision") and guidelines for effective dialogue ("If you can substitute T think' for T feel,' it's not a feeling, it's a judgment"). They indirectly challenge traditional sex roles by asking, "When are you a 'married single'?" and telling how they became less isolated by sharing more of their work and play with their partners. Couples at an ME weekend learn by doing. They struggle to communicate, only to come up against their own masks and defenses. The theme of one session is "The Impossible Dream" from the Man of La Mancha; couples are urged to keep on trying, to believe in the dream of a marriage based on love and intimacy.

The stress is on sharing. One problem is that ME tends to ignore the complementary need for privacy, autonomy, the dignity of being allowed to cope with one's own problems. Along the same lines, Mary Vander Goot (1982) speaks of the need for "immersion" in a relationship, followed by "emergence" into a stage where independence is as treasured as intimacy. ME might do well to consider the process of emergence, and ways married people can help one another at this stage. On the other hand, each couple enjoys a great deal of privacy on the weekend. They need not discard their own value system or conform to anyone else's ideals in order to benefit from the ME tools of communication.

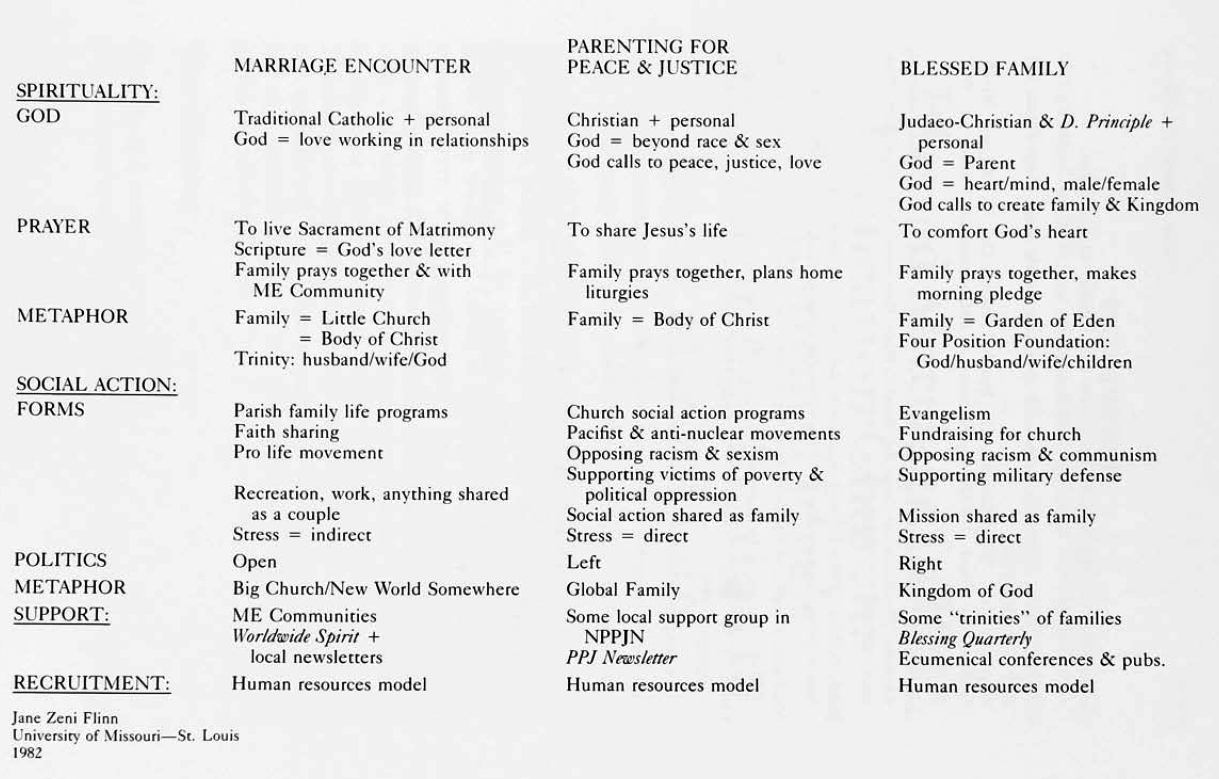

One of these tools is prayer. God is Love working in human relationships. So if a man and woman share their deepest selves, they will share their experiences of God. Couples are encouraged to pray together, and to dialogue on passages from scripture ("God's love letter to us") or on such questions as "How do I feel when I know you are God's gift to me?" The image of God in ME is traditionally Catholic. Yet the stress is on a very personal spirituality, a willingness to trust and share with God as with one's marriage partner. Several metaphors are used to express the M E ideal. Couples are told that the Sacrament of Matrimony is their special source of grace, their calling to become the Body of Christ: "Love one another as I have loved you." An encountered couple is compared to the Trinity -- husband and wife united in the Spirit. The family itself is called the "Little Church" -- one, holy, catholic, and apostolic -- sharing love in the home, in prayer, in the church, and in the world community.

ME looks at social action indirectly, as a natural result of the sharing that starts in the family. Each M E weekend, following a prescribed format, starts with a session called "encounter with self." Then come sessions on "encounter with spouse," "openness to God's plan," "the sacrament of marriage," "matrimonial spirituality," and finally "sharing couple power." Thus the program creates a widening circle of relationships. A couple's love, acceptance, and faith provide the atmosphere that fosters healthy children. M E suggests that this same atmosphere can transform the church and the civil community. Wouldn't it be wonderful, the leaders suggest, if the whole world could be encountered? The ME theme song, "New World Somewhere," reflects this vision that links the person, the couple, the family, and the wider society through God's love.

The vision is just that -- no attempt is made to spell out the economic and social changes that would be needed, or to look at the power of institutions to control or prevent change. The strength of ME is not in social action, but in the intensive training in communication. Yet it is not unreasonable to claim that children raised in an ME environment will gain the self-esteem and communication skills to cope effectively in the world outside the family.

ME is much more than a weekend experience. The key to a deeper, more intimate marriage is the practice of "daily dialogue." Couples are urged to set aside twenty minutes of "prime time" each day -- ten minutes to write, ten minutes to share feelings. (Couples leave the weekend with a calendar and lists of dialogue questions in case they run out of topics.) In many parishes, ME "communities" meet biweekly for dialogue and support. If couples continue with the program, they tend to make changes in lifestyle. They may, for example, move beyond rigid husband-wife roles, beyond the separate worlds of the "married singles," by sharing household tasks and outside interests. They may work on their child raising practices. Older children may be included in "family dialogue" on house rules, love and prayer. The ME journal, Worldwide Spirit, devoted the September 1981 issue to conflict resolution, the use of dialogue to deal more openly and constructively with family problems. Encountered couples are urged to become active in parish and community work related to family values; to share the faith of their "Little Church;" to recruit new M E participants. For many, a marriage encounter weekend is both an emotional peak experience and the start of a new way of life.

The Institute for Peace and Justice in St. Louis was founded in 1970 by James and Kathleen McGinnis. In 1980, the Institute developed a National Parenting for Peace and Justice Network to provide resources and workshops for families trying to "integrate social ministry and family ministry" (McGinnis, 1981: 3). NPPJN is now an ecumenical movement led by parent teams in more than twenty cities.

PPJ programs attract religious educators, social workers, academics, homemakers, and church leaders -- both couples and singles. At a recent St. Louis workshop, most participants were in their thirties and forties, a few younger. The group was more homogeneous than ME, consisting largely of college educated people who had been active in the peace and civil rights movements of the sixties. They now wanted to build on these values in raising their own families.

A PPJ workshop may fill two and a half days of a single weekend, or seven evenings spread over as many weeks. Cost is about $35 per person, but fees are adjusted according to ability to pay. The group generally meets at a retreat house under the leadership of a couple trained in previous PPJ programs. Most sessions follow a lecture-discussion format, making the atmosphere more casual, less intense, than an ME weekend. Films, individual worksheets, and small group sharing help people analyze such problems as racism, sexism, violence, and poverty in the context of their own families and communities. The whole group then brainstorms more constructive approaches, which the team leaders record. For the evening meal, everyone is invited to the homes of host families, and out-of-towners may be overnight guests.

In contrast to Marriage Encounter's stress on the couple, the focus in a PPJ weekend is on the entire family. Parents are taught some of the skills of group leadership. They discuss ways to reduce conflict, listen to feelings, create an affirming atmosphere, and raise more responsible, caring children. The key to democratic process in the home is the family meeting where feelings can be aired and group decisions made. Participants role playa problem-solving session. They talk about how to prepare a meeting agenda, and when to let children take turns chairing.

PPJ helps parents analyze the hidden curriculum, the values and beliefs that underlie the ones they think they are teaching their children. The first theme is stewardship. How does our lifestyle confirm the materialism of the wider society? How can we challenge it? Participants share ideas for simplifying the family diet, budget, recreation, holidays, and energy use. They examine the influences of TV and advertising, and suggest ways they have taught their children to be critical viewers and consumers.

Next the group considers how non-violence can be taught through daily experience in the home. Fighting children, gun play, media violence, spanking, and the use of parental power -- when families deal with these issues they are also dramatizing and teaching about the issues of war and peace. The emphasis is on helping children solve their own conflicts.

Finally, parents explore the possibility of a multicultural and nonsexist family life. They probe their own unstated stereotypes: Who does the laundry? Who pays the bills? Who stays home from work when a child is sick? And they look at the role models their children see: What color is the pediatrician? The teacher? The babysitter? What messages about race and sex do children pick up from their books, movies, and family recreation? Parents are challenged to change -- gradually, one step at a time.

Prayer is stressed as the source of strength and unity in the PPJ family. "The divorce of spirituality from social action, or of faith from good works, has in the recent past produced both some burned-out activists and some navel-gazing contemplatives" (McGinnis, 1981: 113). Instead, children can experience the call from Jesus to work for peace and justice. Spontaneous family prayer is suggested at meals, at bedtime, at home liturgies, on camping trips. Here, the open democratic style of the family meeting spills over into family worship. God is described as beyond race and sex, yet close enough tor a personal relationship with a child, working in history for peace, justice, and love. As in ME, the family is called the Body of Christ, a key metaphor suggesting that each member brings about the life and harmony of the whole.

PPJ spells out more directly than M E the roles of parents and children in the Body of Christ writ large, the global family. The leaders explain that even young children will care about social action provided the issues are made real to them: they need personal contact with victims of injustice, and a concrete role suited to their level of maturity. Members share experiences with volunteering at the Catholic Worker House, sponsoring children abroad, supporting self-help crafts centers, writing letters to government officials, boycotting products of certain companies.

Most of the suggestions are not new. In fact, they are much like the projects many PPJ adults worked on fifteen years ago as student activists. What is new about the program is that it translates social values into real family situations. Refusing a Nestle candy bar does more to raise a child's consciousness than to promote change in the company's marketing practices. The strength of PPJ -- like ME -- lies in its view of the family as an educational center for learning positive human values. The theme is expressed in the song, "Let there be peace on earth, and let it begin with me."

PPJ is too new to evaluate the long-term impact of the workshops. Participants take home a stock of ideas in the form of two books plus their own worksheets and notes. A quarterly newsletter alerts them to such issues as violence and sexism in toys, or Christmas without conspicuous consumption. Families are encouraged to promote the network by requesting speakers, films, and tapes for parish and school groups. In St. Louis the Institute for Peace and justice is available for follow-up meetings; in other cities support groups and team leaders keep members in touch. But the structure most basic to PPJ seems to be the family meeting, where conflict resolution, prayer, and social action meet in the home.

The Unification Church, led by Korean evangelist Sun Myung Moon, has gained members in every nation in the non-communist world. Rev. Moon's system is based on the Old and New Testaments, and spelled out in Divine Principle (1959 -- English edition, 1973). Unlike most Jews and Christians, Unificationists place marriage and the family at the very center of God's plan for the world. Marriages are arranged by Rev. Moon, and children that are born to these "blessed couples" have a special status in the church. The first 36 couples were married in 1961; today there are almost 3600 Blessed Families, some with children already old enough for marriage.

Becoming a Blessed Family is a good deal more complicated than getting into Marriage Encounter or Parenting for Peace and Justice. The Blessing, or wedding, takes place two or three years after a couple is matched (engaged). And to be eligible for matching, one must have been a member of the Unification Church in good standing for about three years, leading a disciplined life of celibacy, church service, and evangelism. The church recruits and trains converts through a variety of weekend, one week, and three week workshops. There is no cost for the training itself, but during the period of apprenticeship most American members must work fulltime for the movement, taking only a subsistence income. A 1976 survey revealed that most U C members come from middle-class families and had at least some college background. In their teens many experienced a loss of religious meaning, and a subsequent disillusionment with the counterculture and the peace and civil rights movements. Today they find in their church a new call to change the world (Judah, 1981: 1, 4-5).

The Unification Church does not provide workshops specifically to prepare couples for the Blessing. There is, however, a pattern of implicit training. Each convert is guided by a "spiritual parent," and all church work is performed by teams led by designated "mother" and "father" figures. The system is intended to teach family roles as well as group cooperation. The growing "home church" movement exposes single members to couples who are actively living their church ministry and serving their community. Religious education materials such as the Outline of the Principle (1980) help to clarify the marriage relationships, spiritual life, and social action expected of Blessed Families.

Male and female are seen as complementary opposites, like the Oriental yin/yang or the anima/animus of C.G. Jung. Thus a husband and wife need one another for wholeness, to develop "heart." Parenting a Blessed Family is the highest goal of individual human life, the model for all other relationships. The system suggests the possibility of equal and flexible roles tor men and women. In practice, however, the Blessed Family tends to have rather traditional sex roles, a reflection, perhaps, of the male-dominated Biblical and Oriental societies. There is also a tendency to reinforce the stereotypes of male (active, dominant, intellectual) and female (passive, receptive, physical), an issue debated both in the church and outside (Getz, 1982).

Far less traditional are the racial attitudes fostered in the Blessed Family. Rev. Moon deliberately brings together couples from diverse nations, races, religions, and social backgrounds. A multicultural family is prized as a microcosm of the world community of the future. Unfortunately, at present there is no formal preparation for the challenges of a multi-cultural lifestyle. Oriental and American Unificationists, for example, may assume very different norms for the behavior of "mothers," "fathers," and "children." Blessed couples have struggled to define these roles in a way that makes communication possible.

Child raising in the BF is a mission. Children are to be the forerunners of a new age, committed to justice, love, racial equality, church service, discipline, sexual morality, economic stewardship, and anti-communism. How these values are to be taught is rather vague. As the BF age and their children increase, it seems crucial that they map out their own patterns tor socializing the next generation. They might, for example, adopt the M E dialogue to deepen communication within the couple, or the PP| family meeting to translate social issues into everyday life experiences. They might look to successful multicultural families outside the church to raise their own consciousness of stereotypes and of ways to counter them. Parents can, for example, show their children how to cope with prejudice, ignore stares, answer questions simply, and accept themselves with a bit of humor (Flinn, 1981).

Most children are raised in nuclear families, but community child care is common since one or both parents may be called away for periods of missionary work lasting months or even years. These long separations contradict the stated ideal of Unificationist marriage. Although most BF accept such sacrifice as part of their calling, they may experience major tensions (see Barker, this volume).

Blessed couples see their role as establishing "God-centered families." Rev. and Mrs. Moon are described as the True Parents, the model for other Unificationists. A Blessed Family gathers each morning for prayer and a pledge of commitment. Spontaneous family prayer is encouraged as a way of relating to God with "heart" as well as with intellect. To the BF, God is not only heart and mind, but also male and female, the image of the ultimate parent. The key metaphor is the "Four Position Foundation" -- God/ Mother/Father/Children -- which identifies the family with the very principle of creation. Divine Principle says, for example, that the BF recreates the Garden of Eden. Children are taught that God weeps over the sin and suffering in the world, and longs for them to build his Kingdom on earth.

Building the Kingdom of God requires concrete action. Witnessing, fundraising, recruiting church members, and religious education involve children as well as parents. Like PPJ -- and more directly than ME -- Blessed Families organize to promote change in the larger society. For example, church teams have been assigned to large scale missions witnessing on college campuses. Blessed Families have expressed their political views in rallies against communism or in favor of military defense. (It is interesting to note that God's will is linked to the political "right" in the BF and to the political "left" in the PPJ, although neither group can be neatly pigeonholed.)

The BF has less community support in the U.S. than in Japan or Korea, where the U C is stronger. Through a system of God-coupling, three families may be matched as a "trinity" which meets to pray, share experiences, and support one another. The Trinities are still more of an ideal than a reality in the U. S., and since prejudice against the Unification Church can make other social life difficult, some Blessed Families experience a sense of isolation. The Unification Church maintains a family life office with responsibilities ranging from religious education to marriage counseling. Former director Nora Spurgin, a social worker, also edits the Blessing Quarterly, a periodical with a circulation of about 1000. Blessed couples submit articles to the Quarterly sharing the challenges of missionary work, the pain of marital separations, and insights on child raising and family spirituality. In addition, the Unification Church sponsors a wide range of ecumenical conferences, a few of them dealing with the family. In May 1981, five Unificationist couples spent a weekend with six couples from other faiths discussing marriage, children, religious education, and the theology of the family. Publications of such conferences give the Blessed Families a growing body of literature and contact with a wider community sharing similar goals.

Marriage Encounter, Parenting for Peace and Justice, and the Blessed Family suggest new directions for the nuclear family. They show that the nuclear family need not be patriarchal, authoritarian, ingrown, materialistic, a mere reflection of the values of its society. In fact, they suggest that the family can be an effective source of change. The family can offer a critique of current values by providing a place where children can learn more peaceful, more loving, more spiritual, more socially committed ways of living.

All three models give practical help to people who want to change. They deal with problems of sex roles, prejudice, love, conflict, and communication in the home. They are based on a broader spiritual sense of family, and encourage parents and children to pray together. They see the family as the image of God and of God's work in the world, drawing members beyond their nuclear relationships to a sense of mission and social action. The term "global family" can be a gross oversimplification. But, its use can teach children that what they do at home is relevant to the problems they will face in the wider world. As Virginia Satir says,

Troubled families make troubled people and thus contribute to crime, mental illness, alcoholism, drag abuse, poverty, alienated youth, political extremism, and many other social problems....Everyone who holds a position of power or influence in the world was once an infant. How he uses his power or influence depends a good deal on what he learned in the family as he was growing up. If only we can help troubled families become nurturing -- and nurturing ones even more nurturing -- the impact of their increased humanity will filter out into government, education, business, religion, all the fields that determine the quality of our lives. (Satir, 1974: 18-19).

ME, PPJ, and BF bring quite different answers to the dilemma of the modern family. When viewed as educational structures, however, they show striking similarities. All three use the human resources model: a core group is trained, then immediately sent out to recruit and train new members. Unlike hierarchical churches and social institutions, these groups need not develop a class of highly trained leaders with a mass of weakly-committed followers. Modes of behavior are learned by doing -- books and lectures may support but not replace the direct experience.

The human resources model is not new. It was used by St. Paul and other early missionaries to spread Christianity throughout the known world in less than a generation (Donovan, 1978). Today it is the model for a score of self-help programs beginning with Alcoholics Anonymous, and for such effective staff development programs as the National Writing Project. The human resources model makes possible rapid growth along with strong individual commitment. It is a style of education well suited to send God-centered families into a world community.

Today's couples cannot return to the models of the fifties, the thirties, or some imagined golden age. But they can learn ways to transform the nuclear family. They can look to the contemporary models of Marriage Encounter, Parenting for Peace and Justice, and the Blessed Family -- and perhaps move on to create new forms.

Barker, Eileen. "Doing Love: Tensions in the Ideal Family." In this volume. Divine Principle. New York: Holy Spirit Assn. for the Unif. of World Christianity, 1973.

Donovan, Vincent. Christianity Rediscovered: An Epistle from the Masai. Notre Dame, Ind.: Fides/Claretian, 1978. Flinn, Jane Zeni. "Many Cultures, One Family." America, Oct. 31, 1981, pp. 261-63. Gallagher, Fr. Chuck. The Marriage Encounter: As I Have Loved You. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1975.

Getz, Lorine. "Hermeneutics of the Future: A Feminist Critique." In Hermeneutics and Horizons: The Shape of the Future. Ed. Frank K. Flinn. Barrytown, N.Y.: Unif. Theo. Seminary, distr. Rose of Sharon Press, 1982.

Judah, Stillson. "From Political Activism to Religious Participation: A Study of Conversion in Some American Youth Cults." New ERA Newsletter, 1, no. 3 (1981), 1, 4-5.

McGinnis, Joseph and Kathleen. Parenting for Peace and Justice. New York: Orbis Books, 1981.

Outline of the Principle: Level 4. New York: Holy Spirit Assn. for the Unif. of World Christianity, 1980.

Satir, Virginia. Peoplemaking. Palo Alto, Calif.: Science and Behavior Books, 1974.

Spurgin, Hugh and Nora. "Blessed Marriage in the Unification Church." In this volume.

Vander Goot, Mary. A Life Planning Guide for Women. New York: Edwin Mellen, 1982.

For Further Information

The Blessing Quarterly, c/o Holy Spirit Association for the Unification of World Christianity. 4 West 43rd St., New York, NY 10036.

National Parenting for Peace and Justice Network Newsletter, c/o Institute for Peace and Justice. 4144 Lindell #400, St. Louis, M O 63108.

Worldwide Family Spirit. 1097 Jefferson Ave., Akron, OH 44313. Worldwide Marriage Encounter Headquarters. 3711 Long Beach Blvd., Long Beach, CA 90807.