![]()

Unification Theology In Comparative Perspectives - Edited by Anthony J. Guerra - 1988

|

|

Unification Theology In Comparative Perspectives - Edited by Anthony J. Guerra - 1988 |

A significant feature of Dr. Kim's theology has been her willingness to utilize the findings of historical-critical biblical scholarship. While Divine Principle was written by people in dialogue with fundamentalist missionary Christianity and either interprets the Bible assuming a hermeneutic of biblical literalism or, in some cases, disputes with an audience which holds to that hermeneutic, the metaphysical truth which that text expounds can hardly be constrained to that particular approach. Dr. Kim's writings have exhibited a notable openness to a wide range of expressions of Christianity, from orthodox to liberal. Divine Principle itself gives the theological basis for recognizing the value of a multiplicity of approaches to scripture, including the modern scientific approach of biblical criticism, to uncover a meaning beyond the literal sense:

The Bible, however, is not the truth itself, but a textbook teaching the truth. Naturally, the quality of teaching and the method and extent of giving truth must vary according to each age.... Therefore, we must not regard the textbook as absolute in every detail. (Divine Principle, 9).

Rarely is historical-critical research more supportive of Unification theology than in its interpretation of Genesis 3 as a basis for a sexual interpretation of the human Fall, as Dr. Kim herself has realized.1 There is a growing consensus among biblical scholars that a polemic against Canaanite fertility cults with their rites of sacred prostitution is a substratum of the narrative in Genesis 2-3- While some recognize this polemic to shine transparently through in the Yahwist's rendition, there are many who understand the Yahwist to have attenuated many of the polemic's sexual themes when he took it up into his epic narrative. I would contend that although the symbolism in the narrative appears somewhat opaque to us, the people of ancient Israel readily understood the story's polemical intent and its sexual connotations because the fertility cult was a living part of Israelite culture.

After reviewing the ancient Near Eastern background of the Fall narrative in Genesis in order to illuminate its original meaning, my second task will be to relate this to the Unification teaching on the Fall. As revelations by the same God, there is a theological assumption of continuity between the revelation in Genesis and the teaching in Divine Principle. Perhaps we can show that Divine Principle is retelling the original sin of the Fall for our contemporary situation, where the idolatry of fertility cults has been replaced by other expressions of the same sin. Unification theology approaches the Fall with a renewed seriousness in an age that has come to idolize casual sexual relationships as a way of love, happiness, and maturity -- the very promises of the fertility cult which the Genesis account had called into judgment.

The range of modern interpretations of Genesis 3 can be quickly grasped by considering the range of possible meanings for the crux "knowledge of good and evil." The verb "to know" (ydda') has a wide range of semantic meanings. First, some have understood it to mean knowledge in the moral sense.2 This view, popularized by psychoanalysis, views the Fall as that primordial event where humankind lost its innocence and was for the first time capable of making moral decisions. In other words, attaining knowledge of good and evil means to reach the age of maturity or adulthood. Two biblical parallels which could support this interpretation are Deut 1:39, where the children of those who made the exodus are called those "who to this day have no knowledge of good or evil," and Isa 7:15, where the child Immanuel will eat curds and honey once he grows out of childhood -- "when he knows how to refuse the evil and choose the good." Yet these parallels do not require a moral interpretation, and could equally be construed as denoting maturity in a physical, intellectual, or sexual sense. In the Genesis account, the couple in Genesis are already treated as moral agents when God addresses them and imposes the commandment upon them. Furthermore, if this "knowledge," which God purposefully hides from humanity, were moral sensibility, it would contradict the entire sweep of biblical thought with its repeated emphasis on God as the revealer of moral law.

Second, the "knowledge of good and evil" can refer to all the secrets of nature, the totality of knowledge,3 or knowledge of the magic arts.4 Adam and Eve are offered knowledge of everything in creation, or in other words, divine knowledge. Thus according to the words of the serpent in Gen 3:5, repeated by God in 3:22, by their eating the fruit they become like God. This sense of knowledge of good and evil as the totality of wisdom, knowledge in the experiential, moral and intellectual senses, is the meaning preferred by the majority of scholars today. Yet this proposal appears to be contradicted by the text, where Adam already has the power to give names to all the animals, hence to rule over them. Adam already had considerable knowledge about the world.5 The wisdom of Adam before the Fall is explicit in the variant of the Garden of Eden story in Ezek 28:12 where the king of Tyre is likened to unfallen Adam in the Garden of Eden: "You were the seal of perfection, full of wisdom, perfect in beauty." Similarly in Ps 82:6, the judgment upon the divine beings, who presumably already possess divine knowledge, is likened to the fall of Adam: "I said you are divine beings, sons of the Most High all of you. Nevertheless you shall die like Adam, and fall like one of the angels."6 However these parallels should not be overdone; Adam in the Genesis account is clearly not a divine being but rather aspires to divinity. The fabled knowledge of primordial man7 may be a variant tradition to that in Genesis 3, which intentionally portrays Adam as a weak-willed and inexperienced person who seeks knowledge but is not yet wise. As we shall see, there is merit to understanding the cryptic phrase "knowledge of good and evil" as encompassing the totality of wisdom, but this is not its only meaning, nor is this meaning the key to interpretation of the text.

Third, the verb "to know" in Hebrew often denotes a man having sexual relations with a woman. In Gen 4:1 Adam "knew" his wife, and she conceived and bore Cain; Gen 24:16 describes Rebekah as "a virgin who no man had known," and in Gen 19:5 a mob of Sodomites demands that Lot and the angels be given to them that they may know them, that is, rape them. A frequently cited parallel is 2 Sam 19:35, where the aged but sagacious Barzillai declines David's offer of hospitality at the court and bargains on behalf of his successor:

I am now eighty years old; can I discern between good and evil? Can your servant taste what he eats or what he drinks? Can I still listen to the voices of singing men and singing women? Why then should my servant be an added burden to my lord the king?... but here is my servant Chimham; let him go over with my lord the king.

Here Barzillai's inability to know good and evil cannot refer to lack of moral sense or to senility; Barzillai is only mentioned here because he was a powerful leader of Gilead. In the context of a list of the pleasures of the court, it likely refers to the missing element of the triad "wine, women and song."8 The sexual interpretation can also encompass the references to maturity in Deut 1:39 and Isa 7:15; the age at which children can know good and evil is then the age of puberty. In this regard Gordis adduces a passage from the Qumran text sereh ha'edah QSa 1.9-11:9

He shall not come near to a woman, in order to have sexual relations with her, until his completing twenty years, when he knows good and evil.

Obvious sexual elements are woven into the Genesis story.10 The couple are at first naked, but they are ashamed following the act and cover themselves with fig leaves -- a dress which was connected with sexual orgies. The expression to eat a fruit was itself a common euphemism for sexual intercourse, thus Gilgamesh 6.1.8 has Ishtar trying to seduce the hero: "Come, Gilgamesh, be thou my lover/Do but grant me of thy fruit." The Hebrew has wordplay of the roots 'ur "arouse," 'ry "nakedness", 'rm "cunning" and 'ur "skin." The curse on the woman involves the sexual domain of life.

Our understanding of the sexual nature of the Fall narrative is illuminated by a number of extra-biblical parallels, notable among them the Mesopotamian epic of Gilgamesh.11 There the story of Gilgamesh's companion, the wild man Enkidu, shows many parallels to the Genesis account of Adam's creation and fall. Enkidu, like Adam, was made out of clay and given the "essence" of a god (1.2.34-35). He goes about naked, lives in the wild among the animals, waters with the beasts at the watering-places, and knows nothing of humanity or civilization. Gilgamesh sends a temple-prostitute to seduce him and alienate him from his life in the wild so that he will come into the civilized world:

The lass freed her breasts, bared her

bosom, and he possessed her ripeness.

She was not bashful as she

welcomed his ardor....

After he had had his fill of her

charms,

He set his face toward his wild beasts.

On seeing him,

Enkidu, the gazelles ran off,

The wild beasts of the steppe drew

away from his body.

Startled was Enkidu, as his body becomes

taut,

His knees were motionless -- for his wild beasts had

gone.

Enkidu had to slacken his pace -- it was not as before;

But

now he had wisdom, broader understanding.

Returning, he sits at

the feet of the harlot,

He looks up at the face of the harlot,

His

ears attentive, as the harlot speaks;

She says to him, to

Enkidu,

"Thou art wise, Enkidu, art become like a god!

Why

with the wild creatures dost thou roam over the steppe?

Come, let

me lead thee to ramparted

Uruk..." (1.4. 16-36)12

The result of their lovemaking was that Enkidu, like Adam, was forced to leave his wilderness paradise and bend himself to the task of civilized life. Yet this act also gives Enkidu wisdom, and he becomes like a god -- the very words Gen 3:5,22 uses of Eve's and Adam's wisdom which they gain upon eating the fruit of the tree of knowledge. Here wisdom is both the knowledge of sexuality and knowledge of human affairs and civilization, to which Enkidu now repairs. Enkidu's next acts reflect this two-fold aspect of his new knowledge: he puts on clothing, a piece of the woman's garment (2.2.27-30) and then goes to live with shepherds to learn the ways of men. Finally it is Enkidu's lot to die, and he curses the harlot for enticing him to a path that had such an unfortunate outcome (7.3-10-30). Like the curse on Adam in Gen 3:19, Enkidu turns to the clay from whence he came (10.2.12).

However, the difficulties of the sexual interpretation should not be overlooked. Sexuality per se is not prohibited by God, who sanctions the marriage bed in both the J and P creation accounts (Gen 1:28, 2:18,23-24). The Fall is not about divine displeasure over sex in marriage, which is rightly viewed by the Jewish and Christian traditions as God's blessings to humanity.13 Rather, the narrative must be referring to sexual relations outside of marriage. In the ancient world, we know of an institution which required extramarital sex, which promised life, fertility, and communion with the divine, and whose symbols included serpents and trees, namely the Canaanite fertility cult. Genesis 3 finds its proper historical context as a polemic against the fertility cult and its claim to be a way to participate in the life of the gods.14

We know that the fertility cult persisted in ancient Israel by its frequent condemnation by the prophets. Throughout the ancient world it venerated the agricultural goddess of fertility, known in different locations by various names as Aphrodite, Asherah, Ishtar, Astarte, etc.15 It was thought that the fertility of humans, crops and cattle was the result of the sexual union of the gods, the hieros gamos. The blessings of their union were communicated through its ritual reenactment by the worshipper and a temple prostitute. The Bible associates these male and female prostitutes, called "holy ones" (qades and qedesah), with the goddess Asherah.16

The cult of Asherah was ubiquitously associated with trees or wooden posts called Asherahs.17 In Punic iconography, Asherah, there called Tannit, was often depicted beside a fruit-bearing palm tree. According to the testimonies of Hosea and Jeremiah, her cult of ritual sex was practiced underneath the shade of trees or beside her wooden standards.18 A tree is similarly the setting for the sin of Genesis 3.

Asherah was also symbolized by the serpent. Her various names included Ugaritic 'atiratu yammi, "treader on the sea-serpent," Punic tannit, "serpent goddess," and in the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions b'lt dt btn, "lady of the serpent."19 She was also called qudsu, "Holiness," 'elat, "the goddess,"20 and rabbat, "the lady." Archaeologists have found a series of Syrian and Egyptian plaques and statuettes of Asherah under the name Qudsu. There she is a nude goddess, her hair in flowing curls, standing on a lion and holding one or more serpents (Figure l).21

Asherah as the chief goddess in the fertility cult is also the figure alluded to in the Fall narrative's depiction of Eve. Eve is called "the mother of all the living" (Gen 3:20) which resembles the role of Asherah as mother goddess. Even more revealing are Eve's words upon the birth of Cain: "I have procreated (qnyty) a man with Yahweh" as if she, like Asherah, was the high god's consort. Asherah was similarly called at Ugarit "creatrix (qnyt) of the gods." In Hebrew Eve's name hawwa. is related to an Aramaic word for serpent (hiwyat), leading Genesis Rabbah to make a play on words with Eve's name, "the serpent is thy (Eve's) serpent, and thou art Adam's serpent." Hawwat is even a name for Asherah in an intriguing Punic inscription which begins "O Lady hawwat, Goddess."22

Although Genesis 3 makes every effort to portray the serpent as simply an animal, its intelligent speech makes it transparent that the Yahwist is demythologizing and debunking a divinity well-known from Canaanite myth. Indeed, this denigration of a god(dess) to the status of mere animal is part of the narrative's message. But for such a conceit to work, the author assumed that his listeners would know well the myth to which he was alluding. In the religious lore extant both in Israel and among the pagan Canaanites, the serpent appears in two different contexts. He is the primordial chaos dragon, personified as Sea, who challenges the gods for control of the cosmos but is defeated. This is the biblical dragon Leviathan (Isa 27:1, Job 41). But the wiley serpent in Genesis 3 is hardly a warlike monster. The other serpent in Canaanite lore is a wise and benign animal symbolizing healing and immortality. The bronze serpent of Moses was used to heal victims of a plague in the desert (Num 21:6-9). The Greek Caduceus, symbol of medicine, was a pole with entwined serpents which several scholars have connected to the Canaanite-Phoenician serpent.23 In the Gilgamesh epic, the serpent became immortal after stealing the plant of life, and his immortality is evident because he renews himself whenever he sloughs his skin. This is in character with the serpent in Genesis 3; he holds out the promise of immortality. It is also in character with the purpose of the fertility cult, to elicit life and healing by imitation of the gods (cf. Num 25, where the licentious rites of Baal Peor were performed to avert a plague).

We now turn to an Ugaritic text which illuminates the connection between serpents and the fertility cult, RS 24.244.24 A birth-goddess or horse-goddess named phlt addresses each of the major gods and instructs them to perform an incantation against snake-bite:

"Incant the bite of the serpent,

the strike of the serpent,

the slougher.

From it let your charm

destroy,

from it let it dispel the venom."

Each God then prepares a couch and sits down for a purpose that may correspond to the scene at the conclusion. Then the birth-goddess goes to the god Horan and makes the same request, but he either refuses or is unable to carry out the charm. The spurned goddess casts a spell on Horan which renders him infertile, and Horan, in order to overcome her spell and regain his potency, seeks out a sacred tree, the "tree of death":

Against the Horan she turns her

face,

and bereaves [him] of his progeny,

profaned is the

precinct of the Ancient One.

Lo, he set his face

to the fertile

Tigris region,

the abundant Tigris region.

He dispels with a tree, the

tamarisk,

with a shrub, the tree of death.

"Let the double tamarisk shake it

off,

the double palm shoot remove it,

the double adornment make

it pass,

the double fruit carry it away."

Horan arrives at his house,

he

reaches his court.

His potency is strong like a

torrent,

it streams like unto a stream.

This "tree of death," like the biblical tree of life, is located at the source of the Tigris river, the place of Eden (Gen 2:14). With this tree he does a fertility ritual which restores his potency. The ambiguity of life and death brought by these plants is evident here as in the Bible: the fruit of the tree of death here brings renewed potency, the fruit of the biblical tree of knowledge of good and evil brings death.

Fresh and revived, Horan now returns to the goddess and can overcome her spells in order to consummate the sacred marriage. The sequence and the role of serpents is instructive:

But she had incanted herself in the

house,

she had shut herself in the house,

she had latched

herself in.

[Horan] "Open the house that you

incanted,

open the house so I can enter,

the temple that I can

come in."

[phlt] "Give as a marriage price

serpents,

'the stinger' give as my marriage price,

a young

snake as my love pay."

[Horan] "I have given serpents as

your marriage price,

a young snake as your love pay."

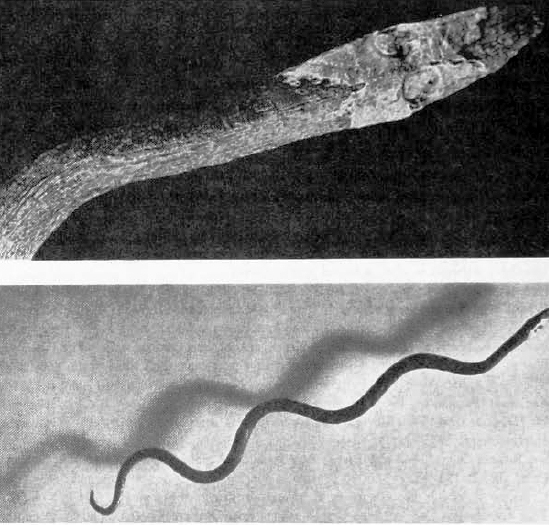

The goddess will not let Horan enter until he has given her snakes as a marriage price (fnn). In the Bible 'etndn is the term for a harlot's hire, which is again bound up with the rite of sacred prostitution; it is dedicated to a deity25 and is mentioned as a form of idolatry and apostasy.26 Coote suggests that the bronze serpent figurines which are found at many Canaanite sites might have been a form of 'etndn for the cult prostitute (Figure 2).27 Upon paying this price of tamed serpents, Horan can enter his temple and together with the goddess fulfill the sacred marriage to bring healing and fertility.

The role of the serpent is here ambivalent, as the source of death through snake-bite or the source of life as a phallic symbol. This text describes sacred marriage as the consequence of taming the serpent's powers of death. Hence the fertility cult was used to elicit healing of diseases, represented by the god's power to incant the serpent. It could neutralize the threatening aspect of the serpent, its powers of treachery and death, which are apparent both in the epic of Gilgamesh where the serpent steals the plant of life and in the Genesis story of the Fall where the serpent tempts Adam and Eve to sin and consequently to their death.

In Genesis 3, the Yahwist generalizes a polemic against the fertility cult and attributes to it the source of all human corruption. In these chapters he is setting the stage for the description of God's redemptive work beginning with Noah and Abraham. The scene in chapter 3 contains all the elements of the hieros gamos: the setting on the sacred ground of the garden of God, the tree as cult-place of Asherah and source of healing and immortality, the serpent as symbol and mediator of the fertility cult, the woman called by one of Asherah's titles, and the man. Together they do something which is supposed to make the couple like God, allowing them to partake in divine life. They seek what all those engaged in the ritual sex of the fertility cult were promised: participation in the numinous power of the hieros gamos. The serpent's words "you will be like God" express this very action of sexual ecstasy and sympathetic magic which was thought to temporarily mingle human and divine energies to bring healing and fertility into the human world.

But the biblical account turns these blessings into curses; the fertility cult's promise of divinity is revealed to be a cheap deception that creates a barrier to attaining the tree of life. The results of the sacred act are nor the blessings of fertility, progeny and eternal life, but rather the curses of infertility, pain in childbirth, and death. The curse on the woman is that she will multiply -- not children but pains in childbirth. Instead of dominating the powers of procreation through the fertility cult, woman would be ruled by her desire for her husband. The ground would not yield crops in easy abundance as promised by the fertility cult; no ritual technique could substitute for human sweat and toil. Finally, as Coote points out, the curse upon the serpent destroys its role as mediator of the fertility cult by placing eternal enmity between it and humanity.28

The biblical account also demythologizes the deities of the fertility cult; the actors are human or animal. In the world of myth the gods live in a garden paradise on the cosmic mountain by the tree of life. On that sacred ground, represented by earthly sanctuaries such as the temple at Mount Zion, they perform the rite of sacred marriage. But although the persons in Genesis 3 live in the garden of God and represent Asherah and her consort, they are not actual gods. Each is a creation of God and subject to his decree. The Yahwist draws a fundamental distinction between Yahweh and the non-gods of the fertility cult. The two trees in the story similarly function to distinguish Yahweh from the false gods.29 The tree of life representing the life offered by Yahweh is distinct from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil representing the false life of the fertility cult.

The specific promises made to Adam and Eve were that they would become like God and have wisdom, yet each of these promises is perverted by their participation in the false and sinful ritual sex of the fertility cult. As we noted, the fertility cult promised divinization through participation in the sacred marriage and its mystic mingling of divine and natural energies, but in Gen 3 the couple is driven out of the garden of Eden, the divine realm, and no longer has easy access to God who habitually walked through the garden (Gen. 3:8).

The wisdom which Adam and Eve gained through their transgression was similarly perverted. Like Enkidu's wisdom it encompassed more than just carnal knowledge; it led Adam and Eve to the toilsome and ambiguous life of human society. Yet this wisdom, originating with the serpent, was deceitful because it was not based upon God, or in the words of the proverb, "the fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom." Throughout the book of Proverbs there is an explicit contrast between true wisdom which brings life30 and the folly represented by the prostitute which brings death.31 The cult of Asherah may lie in the background of these wisdom traditions, which Israel had taken up and restored by depicting Lady Wisdom and the cult prostitute as mirror-images of one another. In Prov 7:6, Wisdom looks out her window onto the street -- a typical image of the prostitute,32 and in Wis 6:12-16 she herself goes out on the street soliciting customers. In the Dead Sea Psalms Scroll, HQPsa 21.11-17, which parallels Sir 51:13-19, uses imagery of sexual intercourse to depict a young man's experience with Lady Wisdom, now understood metaphorically as a transcendent divine attribute. These traditions suggest that the fertility cult advertised itself as a source of wisdom, a worldly wisdom which Israel condemned as a path to death. For the Yahwist, the wisdom gained by the first couple led to banishment from the tree of life and ultimately to the murder of Abel and humanity's progressive decadence, violence, and corruption.

Finally, the Yahwist placed the Fall at the beginning of human history as the original sin that caused humanity to be driven out of paradise. In the fertility cult the hieros gamos was the primordial act of creation, repeated continually in the yearly agricultural cycle. But in contrast to the cyclical time of Canaanite cult, Israel lived with a linear sense of time born out of its epic tradition, where God acts to save his people in the events of history. Accordingly, while the Yahwist also put his account of the sacred marriage at the creation, at the beginning of time, this corrupted sacred marriage, now the human Fall, no longer functioned as a primordial saving event continually represented in the agricultural year. It became rather the primordial sin, which he juxtaposed against Yahweh's very different saving providence to be enacted in history beginning with Noah and Abraham. The Yahwist recognized Eden to be the original home for humankind, signifying humanity's original fellowship with Yahweh. That fellowship would be renewed through Yahweh's particular historical providence with Israel which could overcome humanity's general tendency towards idolatry. For the Yahwist it would be manifest at the fulfillment of the new blessings to Abraham (Gen 12:1-3) at the time of the Davidic monarchy with its temple on Mount Zion as the dwelling place of God and the new Eden (cf. Isa 11:6-9, a description of the peaceable kingdom on Mount Zion where once again the serpent is tame). As Christians, we recognize the truth in the biblical portrayal of the Fall at the beginning of human history; it explains humanity's alienation from God which would be solved only in the course of history, to be consummated at the coming of the Messiah.

Divine Principle is based upon new revelation. Yet it has continuity with the Biblical account of the Fall as it was originally understood. But why is there any need for a new understanding of the Fall? Why should Unification theology recall those ancient images and themes which had long been repressed in the Christian subconscious? Perhaps the traditional Christian position, that the Fall consisted of disobedience as Adam and Eve sought in their hubris to become like God, is not adequate to get at the root of the mystery of sin.

It is not our task here to evaluate traditional Christian theological positions on the Fall and original sin. We note that at least for Paul, the nature of sin is sufficiently complex that on the one hand, the obedience of Christ unto death overcame the power of sin brought on by Adam's disobedience (Rom 5:18-19), but on the other hand, the Christian must continue to fight the power of sin which still resides in the flesh by a determined struggle to live according to the Spirit (Rom 7:14, 21-25; 13:14). Thus, even the most obedient saints, those fully justified before God, still experience the effects of the Fall as a life and death struggle within their own souls. These internal struggles will continue until a future day of redemption (Rom 8:23-35). The Unification Principle, as a revelation proclaiming the day of the complete liquidation of sin's power over humanity, necessarily looks anew at the problem of the human Fall and at the original sin whose effects are still very much with us.

Unification theology describes the human Fall as an act of adultery, an illicit sexual relationship between Eve and the archangel Lucifer. Human love, which Principle considers to be the central spiritual force of life, was thereby derailed and distorted. The first human pair were meant to grow as brother and sister until the time of their maturity, when they would marry under God's blessing, and thereby the full love of God would dwell in their union. However, in violation of God's commandment, Eve and Lucifer united in a false relationship, and then Eve, her desire awakened, subsequently united with Adam prematurely and against the will of God. Their resultant family was bonded together apart from God and under the dominion of the false god Lucifer. This archangelic being, created as a servant of human beings, came to exercise dominion over them through the force of love in his triangular relationship with Adam and Eve, and hence he left his position in God's world to become Satan, "ruler of this world." Human love, which was meant to be holy and an expression of God's agape love, became degraded, self-centered, and far inferior to the divine love as incarnate in the true man, Jesus Christ.

The Unification Principle's view of the human Fall is largely in agreement with the historical-critical understanding of Genesis 3 as a polemic against the adulterous idolatry of the fertility cult generalized into a description of the origin of humanity's alienation from God. Yahweh had ordained marriage as the proper sphere for human sexuality (Gen 2:24). But Adam and Eve did not respect Yahweh's commandment; instead they prostituted themselves to false gods through idolatrous sexual intercourse. The sin which disrupted the original bond between God and humanity was more than disobedience of Yahweh's commandment; it was that act of illicit love euphemistically termed eating the "fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil."

We can recognize the hand of revelation in the Yahwist's characterization of the primordial human sin as idolatry through ritual intercourse. The fertility cult was a particularly pernicious form of idolatry because it bound the worshipper to its gods with the most powerful emotional force in human life, the force of love. The Priestly writer would remark that by ritual sexual intercourse, Israel "yoked itself to the gods of the fertility cult (Num 25:3). Through this sexual communion the powers and characteristics of these gods infused the worshipper. For moderns the fertility cult appears to be merely a deification of nature. But for the prophets it was something far more sinister, namely idolatry that broke the Mosaic covenant and severed the worshipper from fellowship with God. If Israel was in covenant with God and under God's gracious dominion, then it would live righteously according to the laws of the covenant and would enjoy God's blessing. But an Israel committing fornication with other gods -- and fornication was atypical label for idolatry for Hosea and Jeremiah -- acted corruptly, oppressed the poor and lived according to the false values of the polytheistic nations which had formerly enslaved Israel. For such practices, Israel could expect God's judgment.

Similarly, Unification theology understands the essence of the Fall to be the redirection of human love from God to the false god who is called Satan. The fall is fundamentally an act of idolatry that sets up a lasting allegiance, motivated by the force of love. Since love is the most powerful force, the illicit sexual act "yoked" humanity to Satan's dominion and set up a false family manifesting fallen love. Humanity was meant to live under the gracious dominion of God and thereby express the divine image. But beginning with Adam and Eve, humanity under the dominion of Satan has manifested a flawed nature, unable to fully love, habitually acting out of self-centered desire.

Unification theology also builds upon the Genesis account of the false wisdom gained through the idolatrous love at the Fall. Love is the occasion for the most intimate communication of values and attitudes from one partner to another. At the Fall the first couple, and through them all humanity, acquired a "fallen nature," a mind which inverted humanity's true attitudes and values. This wisdom was not mere intellectual knowledge which could be unlearned by an enlightened teaching; it is grounded in the intimacy of family and seated in the deepest inheritance of the race -- humanity's lineal relationship to Satan incurred at the Fall. This wisdom is fundamentally an idolization of the self and the flesh implicit in the fallen act which sought to attain divinity by human striving and sexuality. It brings with it a fundamental insecurity about the self due to the rejection of God, the ground of human existence and source of true love and happiness. The flesh is placed over the spirit, selfish desires over concern for others, love of self over love of God, selfish pride over honest humility and respect. From this set of false attitudes and values, the "fallen nature," Unification theology traces the multiplicity of human sins, including murder and war.

In sum, while the fertility cult may be viewed as an archaic biblical practice and the biblical polemics against it a curiosity of another age, Unification theology recognizes the contemporary pursuit of pleasure and fulfillment through adultery and casual sex to be its modern equivalent. The pursuit of sexuality outside of its proper sphere of marriage is still a most destructive violation of God's pattern for human life, one with serious consequences for one's capacity to give unselfish love. The Genesis narrative is not only about an event that occurred at the beginning of time; the initial alienation was repeated continually in the fertility cult. Similarly, for Unification theology the original sin is repeated and reinforced in the daily life of millions of people who engage in adultery and casual sex. Just as for the Israelites the fertility cult held out the false promises of divinity, fertility, and wisdom, so in the contemporary world there is a prevalent notion that casual sex and a series of romantic loves will bring happiness, maturity of life experience, and ultimately love. The Unification doctrine of the Fall condemns this lifestyle as the pursuit of a mirage, as fundamentally alienating from the true self and from God, and as begetting irresponsibility, lovelessness, and violence. In modern society, as in ancient Israel, the correct path to the blessings of love and wisdom is through a primary relationship to God and fidelity in family relationships which have God at their center.

In addition, those who realize how deeply stained is the tradition of love out of which they have come will embark upon a religious path that will include a life of self-denial and abstinence from fallen sexual relationships in order to purify the self of the inherited effects of the Fall. However, it should not be thought that sexuality per se is base and sinful. It is rather part of the order of creation, and had it not been for the Fall, it would be a most holy and beautiful communion of divine love. The goal of the religious life is to enable one to receive God's pure love and then to share it with others and to form a God-centered family.

1. Young Oon Kim, Unification Theology (New York: HSA-UWC, 1980) 113-114.

2. E.A. Speiser, Genesis, AB 1 (Garden City: Doubleday, 1964) 26; U. Cassuto, Commentary on the Book of Genesis 1: From Adam to Noah (Genesis I-IV, 8) (Jerusalem: Magnes, 1961) 111-113; L. Kohler, Theologie des alien Testaments (Tubingen, 1953) 158.

3. Good and evil can form a merism, a Semitic idiom of stating the extremes to include everything between them. On "good and evil" as a merism see Gen 24:50, Jer 41:17-18; 42:2-3; Lam 3:38; Eccl 12:14, etc. This is the view of von Rad (Genesis, OTL [Philadelphia: Westminster, 1972] 86-7), Wellhausen (Prolegomena to the History of Ancient Israel [Edinburgh, 1885] 297ff.), and many others.

4. Cf. the Book of Enoch, chs. 7-8, 69. But Enoch is based upon the tradition of the fallen angels (Gen 6:1-4) rather than the story of the Fall. As one of the fallen angels who come down and cohabit with the daughters of men, a certain Gadreel who led Eve astray (69.6) and taught men how to make weapons of war. The sexual motif of the story of the fallen angels and the sexual motifs in the Fall in the garden of Eden may be related, but the nature of their relationship is unclear.

5. Robert Gordis, Poets, Prophets, and Sages (Bloomington: Indiana University, 1971) 199-201.

6. On "angels" as a translation of sdrim, see Dan 10; 13,20,21; 12:1. At Ugarit the sarim were the astral deities who fell from heaven, a mythic representation of the eclipse of the stars at the sun's rising.

7. In rabbinic literature, see B. Shabbat 119b.

8. Gordis, 207.

9. Gordis, 198f. Alternatively, since the Qumran passage is preceded by a description of ten years of study of Torah prior to age twenty, the marriageable age could be construed as at the age of reason. See Howard N. Wallace, "The Eden Narrative," diss. Th.D., Harvard, 1972, 145-55.

10. For further biography of scholars favoring the sexual interpretation, see J. Alberto Soggin, Old Testament and Oriental Studies. Biblica et Orientalia 29 (Rome: Biblical Institute, 1975) 102.

11. These parallels are now generally acknowledged, but when they were first suggested by Morris Jastrow (Religion of Babylonia and Assyria [New York, 1898] 475ff. and W.F. Albright ("Adam and Eve in Babylonian Literature," AJSL 15 [1899] 200-14), they were not well received.

12. Translation by E.A. Speiser in J.B. Pritchard, ed., Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 3rd ed. with suppl. (Princeton, 1969), 75.

13. Against Engnell, " 'Knowledge' and 'Life' in the Creation Story," in Wisdom in Israel and in the Ancient Near East, Vestus Testamentum Supplements 3 (Leiden: Brill, 1955) 103-119, who sees the fall as due to human powers of procreation.

14. Soggin, 102. J. Coppens, La connaissance du bien et du mal et lepeche duparadis (Louvain, 1948).

15. See. W.F. Albright, Archaeology and the Religion of Israel, li-lA, 91.

16. Deut 23:17-18; 1 Kgs 14:23-24; 15:12-13; Hos 4:14. Tamar dressed as such a cultic prostitute to entice Judah in Gen 38:15,21-22. 2 Kgs 23:6-7 speaks of the houses of the cult prostitutes where women make weavings for Asherah. The accusation in Amos 2:7 that "a man and his father go into the same maiden" refers to these cult prostitutes. Herodotus 1.199 describes the Mesopotamian institution of the sacred prostitute or qadistu holy to Ishtar as the one time obligation of every woman prior to marriage:

Every woman must once in her lite go and sit in the temple of Aphrodite and there have intercourse with a stranger.... Most seat themselves in the temple precincts wearing a band of plaited gold around their heads... Gangways are marked off in every direction through the crowds of women, by which the men may pass along and make their choice. Once a woman has taken her seat she may not return home until some stranger has cast a silver coin into her lap and taken her outside the temple to lie with her. As he throws the coin, the stranger has to say "In the name of the goddess Mylitta." [The word represents Akkadian muallitu "the one who brings to birth," a title of Ishtar.] The piece of silver may be ever so small, but it may not be refused, and that coin is considered sacred. The woman is not allowed to be choosy -- she must go with the first man who throws her the money. When she has surrendered herself, her duty to the goddess has been tendered and she may return safely home; from that time it will be impossible to seduce het, no matter how large a sum you offer her.

The "plaited cord" may be related to the weavings for Asherah in 2 Kgs 23:7. Quoted in H. W.F. Scaggs, The Greatness that was Babylon (New York: North American Library, 1962)334-35.

17. See Deut 16:21, "plant a tree for Asherah." 2 Kgs 21:2-7 and 23:4-7,14 uses the term Asherah in both senses, denoting the goddess and her cult object. The LXX often translates Asherah as alsos, a sacred grove of trees.

18. Hos 4:12-14; Jer 2:20.

19. F.M. Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic (Cambridge: Harvard, 1973), 32-34.

20. See A. Herdner, Corpus des tablettes en cuneiformes alphabetiques (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1963) 14.197-199 where Kerer "approached Qudsu, Asherah of Tyre, and Elat of Sidon." These three names are of course poetic parallels for a single goddess.

21. These are collected in J.B. Pritchard, Ancient Near East in Pictures Relating to the Old Testament (Princeton, 1969) pi. 469-477.

22. H. Donner and W. Rollig, Kanaandische und aramdische Inscriften (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1979) Nr. 89.1.

23. See Robert Oden, Studies in Lucian's De Syria Dea, HSM 15 (Missoula, MT: Scholars Press, 1977) 151-155.

24. Ugaritica V, ed. J. Nougayrol et al. (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1968) 574-580. This translation and commentary is taken from Robert Coote, "The Serpent and Sacred Marriage in Northwest Semitic Tradition," Ph.D. diss., Harvard, 1972.

25. Deut 23:18; Hos 2:14; Isa 23:18.

26. Mic 1:7; Hos 9:1.

27. Coote, 52-55.

28. Coote, 85-91.

29. The existence of two trees has long caused concern among scholars. Only one tree would be required for the drama of the fertility cult (shorn of its biblical inversion). Some have suggested a conflation of two stories, but no attempt to dissect out separate sources has been successful. For a critique of this approach, see Wallace, 117-121.

30. Prov 3:18,22; 8:35; 9:11, etc.

31. Prov 5:5-6; 7:22-27; 9:18.

32. In the Samaria and Nimrud Ivories the fertility-goddess is often depicted gazing out a window, sometimes wearing a cloth braid, the mark of a prostitute (Jer 3:3), on her forehead. Nor the similar image of the Canaanite Jezebel in 2 Kgs 9:30. See Michael D. Coogan, "The Woman at the Window," paper presented at the Harvard Old Testament Seminar, October 1980.

A bronze serpent unearthed by Rothenberg at the excavation of Timna, a Midianite late bronze age mining center near the Gulf of Aqaba at the eastern edge of the Sinai Peninsula. Found near the altar of the sanctuary, it was evidently a cultic object. Such bronze serpents were symbols of the divine power to heal disease, e.g. the bronze serpent of Moses in Num 21:6-9. Their use in a Midianite sanctuary suggests a connection with the incident at Baal Peor in Num 25.

The Woman at the Window is one of the Nimrud Ivories carved in the Canaanite style, and similar carvings have been found among the ivories from the palace at Samaria. These ivories decorated a bed and are thought to depict Asherah or her votaress gazing invitingly out of her window in the role of a sacred prostitute.

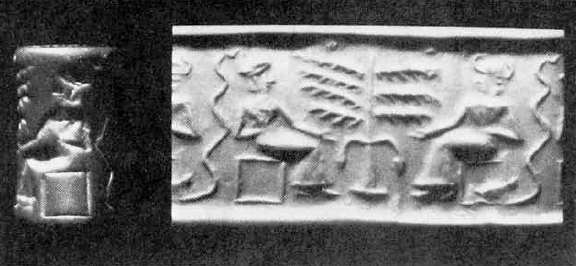

A Mesopotamian cylinder seal depicting a god sitting behind a sacred tree, facing a woman and a serpent. It may be an illustration of a fertility ritual as that depicted in the Ugaritic text RS 24.244. Note that Semitic deities were frequently depicted with horns: horned representations of Baal may have contributed to the later iconography of Satan.

The goddess Asherah (Qudshu) standing on a lion and holding two serpents. This plaque was carved by Syrians living in Egypt in the 7th century B.C. (Drawn from original photo)