![]()

Unity In Diversity - Essays in religion by members of the faculty of the Unification Theological Seminary - Edited by Henry O. Thompson - 1984

|

|

Unity In Diversity - Essays in religion by members of the faculty of the Unification Theological Seminary - Edited by Henry O. Thompson - 1984 |

Gail Sheehy's bestseller, Passages: Predictable Crises of Adult Life, appeared on the bookstands about six years ago and almost overnight placed the hitherto undifferentiated middle years of the adult life cycle in the limelight. Levinson's Seasons of a Man's Life followed along soon after. Eric-son's Identity and the Life Cycles and the works of Kohlberg, Fowler, Wilcox and others on faith and moral development, while not popularized to as great an extent, reflect a growing interest in stages of life. They are also raising the consciousness of our society to those stages and to the changes within them. Many recent books focus on the Christian family and recognize the problems and potential of middle aged parents.1

My husband and I appreciate the opportunity to share our thoughts on "Unification and the Middle Years" provided by this conference. We would first like to provide a frame of reference from the literature on this life stage which is a growing interest in society today. Then we want to share some background for our arrival on the threshold of the "new middle years," concluding with remarks about how being with the Unification Church affects the middle years and how middle year's members contribute to the movement. Preparation for this conference led us to a less well known publication which we have found informative and interesting, Issues and Crises in Middlescence by Joanne Stevenson.

Stevenson provides some historical background and other insights relevant to both family living and middle age. She points out that for centuries only two phases of life were recognized: infancy and adulthood. Other stages of life are only studied and written about when a large number of persons in a certain age range become in some way problematic or troublesome to the larger society. The middle aged have defined the problematic groups: adolescence as a life stage needing study in the 1930s, the elderly as a group with special problems in the 1940s, and the youth of America as a problem group in the 1960s. In the 1970s, the middle aged began looking at themselves.

In 1900 the average age expectancy was 50 years. By 1975 it had increased to 72 years, an increase of 22 years. (A life expectancy of 120 years is projected for people born nearer the twenty-first century!) Stevenson comments, "It is an error to visualize the additional years of life as tacked onto the end. Rather, we should think of them as slipped into the middle."2 She also speaks of the years between roughly age 30 and 50 as the core years of Middlescence-I and refers to the "new middle years," ages 50 to 75, as Middlescence-II.

Our society has certain expectations of those in each life stage. In Middlescence I people are expected to be responsible not only for their own personal growth but also for that of organizational enterprises, for the major institutions in the society: business and industry, government, religion, education, charitable organizations, health care, marriage and family.

The issue here is not whether they do it well or poorly. The point is, they do it. Society expects them to do it. The very young expect them to do it perfectly. The very old expect them to do it better than their own generation did.3

These persons are also expected to provide help to younger and older generations without, however, trying to control them. The developmental tasks of these years include:

1. Developing socioeconomic consolidation.

2. Evaluating one's occupation or career in light of a personal value system.

3. Helping younger persons to become integrated human beings.

4. Enhancing or redeveloping intimacy with spouse or most significant other.

5. Developing a few deep friendships.

6. Helping aging person's progress through the later years of life.

7. Assuming responsible positions in occupational, social and civic activities, organizations and communities.

8. Maintaining and improving the home or other forms of property.

9. Using leisure time in satisfying and creative ways.

10. Adjusting to biological or personal system changes that occur.4

Members of this core middle age group fill many of the leadership positions in society. They also own, control or govern over 90% of the real estate and other forms of property. Stevenson points out that within the norms of our culture, those in middle adulthood are expected to be their own person -- to know how to guide their own lives. However, often they have not learned the skills or gained the confidence to do that and crises then develop.

The author sees as the major objectives of the new middle years (the 50-75 year range) the assuming of primary responsibility for the continued survival and enhancement of the nation at its many levels. The highest positions of responsibility are given to these people -- the presidency, cabinet positions, congressional seats and comparable positions in state or local governments, business enterprises, organized religion, social and civic organizations and the military.

Developmental tasks of the new middle years include:

1. Maintaining flexible views and openness to emerging trends, yet taking responsibility to slow down too rapid acceleration and providing wisdom and restraint.

2. Keeping current on relevant scientific, political and cultural changes.

3. Developing mutually supportive relationships with members of younger generations.

4. Preparing for retirement and planning another career when feasible.

5. Adapting self and behavior to signs of the aging process. In addition, the developmental tasks include a continuation of many of those begun during Middlescence-I:

6. Reevaluating and enhancing one's relationships with a spouse or most significant other.

7. Helping aged parents and relatives through the last stages of life.

8. Deriving satisfaction from increased availability of leisure time.5

Stevenson points out that as children, North Americans are taught to believe that being grown up is one long static plateau. Because the education process has not changed this concept, these false assumptions continue, even among the middle aged and elders themselves. But adulthood can no longer be viewed as one big hunk of life, a plateau reached in the early twenties and maintained until old age or death. Many scientists have found that there are unique features, problems and processes with each decade of adult life. Perhaps these are more culturally than biologically determined but they are the genuine experiences of many persons. There are transitional crises as one passes from one decade to another followed by calmer periods in the middle of the decade. Both the crises and the calmer periods can be growth producing.

Among the transitions identified in middle adult life is the "catch 40" or midlife transition between about 39 and 42, which tends to be a time of discomfort, of coming to terms with reality about the implications of earlier choices, education and experiences. Then, in the mid-forties there is often a troubled period reminiscent of the adolescent years from age 13 to 15. Restabilization usually occurs between 48 and 50. "In contrast to 40-year-olds who focus on what they must hurry up and accomplish in order to fulfill their personal goals, 50-year-olds focus on what they have learned and how they evolved during the half century of their existence."6 Female menopause begins late in this phase and may put stress on the family system or the marriage partners in particular. Separation, divorce and remarriage are relatively frequent in the middle years. Less is known about the ministages and transitions from 45 to 70.

Stresses during the later years may be related to retirement, changes in living arrangements, dealing with aging and the final phases of the climacteric. Illness and death are again crises of this stages of life. Retirement may make people unstable for a time. Moving to a retirement village often creates stress.

Work is important to people in their middle years. As mentioned earlier, persons in this stage carry responsibility for much of the work of an entire nation. Work may occupy the central focus of the middlescent's life. It usually is not just of economic significance -- it also provides structure and continuity to daily living, links individuals to the society and community, provides a means of self-expression and has to do with feelings of self-worth.

Theoretically, some of the business of young adulthood fades with middlescence and then middle aged adults have more time to spend in leisure. For some there will be little distinction between work and leisure, for others a great deal.

Family changes are almost inevitable. By their mid-forties, most American couples find themselves without any small children underfoot. Some develop a closer relationship, others grow apart. Some search for new relationships. Alcoholism, drug dependence, obesity may signal maladaptation in the middle years. There may be stresses from teenage and young adult offspring.

Middle aged persons often accept greater community responsibility than younger or older adults. For some such activity is leisure; for others it becomes a second career

Values Shift. Value reorientation is common in the middle years. There is often a change in attitudes, feelings and behaviors from the mastery orientation of the thirties and forties. By the age of fifty, both men and women report a mellowing of their emotions, feelings and relationships.7 They become more patient and tolerant in their relationships. They tend to live in the present. What one author calls "increased interiority" characterizes the thought life of people in their fifties, reflecting back on their lives.8 To Sheehy's comment that the motivating phrase in the twenties is "I should," in the thirties, "I want," in the forties "I must," Stevenson adds that the phrase that best sums up the fifties is "I am."9

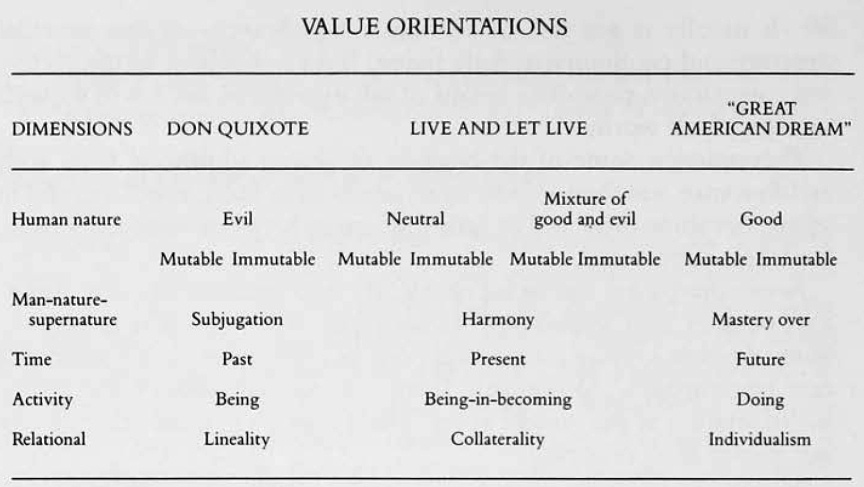

Stevenson, adapting the variations in value orientation chart from Kluckholn and Strodtbeck,10 works from three basic type models: "Don Quixote," "Live and Let Live," and "Great American Dream."

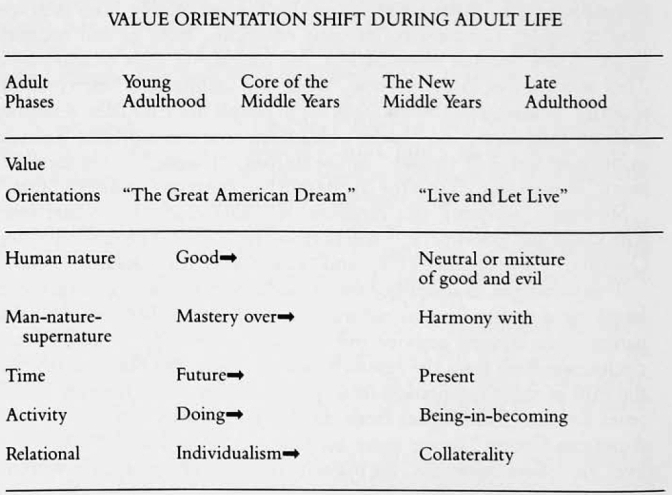

This paradigm, in simplified terms, outlines three distinct world views, based on defining human nature, the relationship between man and nature, time frames, activity and valued relationships. Stevenson concludes, working from the research data of Gould and Neugarten,11 that the shift in value orientation from young adulthood to the new middle years for most adults goes from the more idealistic, futuristic, "Great American Dream" to the more accepting, here-and-now, "live and let live" view. Says Stevenson, the majority of adults are engaged in working on the integrating process of the "live and let live" orientation most of their middle years. She has summarized this in a table.12

There is often a dramatic contrast in the world view and values orientation between general mid-life adult population and those in middlescence who are open to the Unification Church. One distinction of middle-aged Unificationists is their optimistic hope for life and continued efforts to better the world. The value shift from individual orientation ("Great American Dream") to the greater valuing of others seems universal in mid-life, although those who are likely to become involved with the Church sometimes must temporarily sacrifice time with their own loved ones for the sake of working on a community, national or worldwide level.

Being a Unificationist at this point in history clearly affects one's lifestyle regardless of age. Depending on the degree of one's understanding of and commitment to the Church's teaching, active participation will differ. For some in their middle years whose children are grown or who have no children, involvement has often meant full time, unsalaried volunteer work and community life in a Church center.

Because the Church has been comprised primarily of unmarried young adults, emphasis in centers is on outreach, service, fundraising and on personal and community renewal. There are some hearty middle agers who have taken on all of the challenges of younger members -- long days, short nights, limited living quarters and such activities as fundraising and street witnessing. Some participate in Church activities on a part time basis, serving as housemother or assuming special responsibilities. One of the areas of stress that develops for some older members is rejection by or estrangement from former friends or from family because of the controversial nature of the Church and the media's negative impact upon the public.

For some middle agers involved with the Church, peer companionship is provided through jobs or previous interests and commitments. Some may experience age discrimination and be considered too old to take on a foreign mission at 40 or 45 or being ineligible for graduate school at 35. However, the stereotypes about the meaning of middle and older age and about what is appropriate and possible for older people probably exist in the Church to a lesser extent than in the larger society.

The middle-aged members who do live in centers will probably be a minority there. According to 1976 statistics, the percentage of Unification Church members aged 40 and older was 1.9 percent. Persons 29 to 39 years was measured at 20 percent at that time and the younger group, between 22-29, was a predominant 66 percent, and below age 22, 13 percent. There has been some increase in the proportion of older adults participating since the advent of the Home Church ministry and increased community involvement. These middle aged continue to live in their homes, are involved with selected Church activities and serve as a constructive influence in the neighborhoods and organizations to which they belong. Before the alternative of Home Church mission, many adults were limited in their Church activities by the demands of full or part time center life because of dependents or established responsibilities.

Middle aged persons tend to bring a certain stability to Church centers or other Unification work. There are many opportunities to use their knowledge, skills and life experience which they have acquired over the years. One important contribution mature members can make is in the area of relationships between generations as a "mentor" to younger Church "brothers and sisters."

Since the period of provisional adulthood, according to Stevenson, is one of drawing away from the family of origin and lessened dependence on peer support, the 22 to 29 year old is searching for role model adults for counseling and examples.13 Sheehy stresses the value of just such a mentor to the young adult man and woman. The middle-aged adult, who is seen as more proficient and learned than the youth, can teach in an informal manner, help the youth overcome conflicts with their own parents and aid with contacts and experiences that will be useful. Since Unification movement leaders and members are often under thirty, middle-aged members can offer the wisdom and maturity of their years and broaden the intergenerational experience with the Unification family.

The parental role within the center or home church group often falls to the senior member regardless of the time spent within the movement. Since much of Unification philosophy teaches respect and value for parent-teachers, mid-life members quite naturally serve as advisors and resource persons in the personal life of the religious community as well as public and professional relations with the larger community. The older member offers the qualities of patience, confidence and practical experience as substantial contributions to a youthful movement. In exchange, middle-age members receive inspiration and stimulation from young adult members full of physical energy, pure hope and childlike innocence.

One of the greatest challenges for those in the middle years participating in the Church has been to find "spiritual" parental models themselves and to find guides for behavior that is appropriate to both their physical and spiritual age.

Why do middle-aged adults join the Unification movement and what are they looking for in life that they haven't found anywhere else? There may be one clue in the reasons why younger adults join the Church, if it is true that potential members of whatever age abound in idealism. Here Hulme is speaking to ministry professionals and parents when he writes that:

We need to be integrated around a purpose bigger than ourselves -- bigger than our families. Youths are especially sensitive to this need. In their natural idealism they desire to devote their lives to something more than to the accumulation of our society's status symbols. This is one reason why they are drawn to the religious cults that have been the notorious Pied Pipers of recent times. The tune they play draws our children because it calls them to a higher cause.14

There seem to be three situations which attract older adults to a religious movement such as Unificationism in their middle years. First of all are the mid-life individuals, single, separated, or divorced, who are personally searching for meaning and commitment. Either through individual witnessing, professional contacts or media coverage, they learn of the Unification movement and respond by becoming part-time or full-time members.

Richard met the Church in 1979 at the Denver Public Library when he was 37 years old. For the previous ten years he had lived in California, working a variety of construction and repair jobs. In 1975 he was divorced but he continued to share in the care and support of his one son. At the time he met and joined the Church, Richard was considering joining a brotherhood of the Episcopalian Church, intending to attend a seminary in the near future.

Instead, he was attracted to the Divine Principle because it shed great light upon the Bible for him. Richard was also drawn to the Church by the word "family;" he thought that family might be just an old fashioned idea in the modern world but he wanted for it to work. He was grateful to restore his faith in families when he saw successful models in the movement, and in July, 1982, Richard married a wonderful Japanese sister, Kazuyo. For three years in the Church, Richard worked in businesses in Colorado and New York. He currently attends Unification Theological Seminary.

Secondly, there are parents of members who, through their sons and daughters, recognize value in their young adult child's involvement. Through time and study these mid-life adults become involved themselves:

Ann (name changed) is a member of the Unification Church in her early fifties. Her ex-husband is an executive in a large corporation. She is a college graduate and the mother of four children. Her son introduced her to the Unification Church. She later obtained a divorce from her husband (they had been more or less separated for some time). She converted her home into a "mother-child" Church center and became a lecturer in one of the Church's workshop centers. Ann entrusted her 10-year-old and teenage daughter to their father. Not being able to care for them herself was a sacrifice that required Ann's deep faith, for both children faced many problems during their teenage years. Ann is now on the administrative staff of the Seminary and is taking courses part time and preparing to fulfill a long time desire to be an evangelist. In 1978 she also brought her mother into the Unification movement, and later she brought her younger son. Ann is engaged to be married.

Many parent-members have made a valuable contribution to Unificationism by working to establish parent organizations and conferences for other parents of members, in addition to valuable mission work.

The third type of older adult to join the Church seems primarily drawn by their connection to their adult offspring, who is a Unificationist; this drawing power seems to be increased by more than one child in the movement or the marriage of their son or daughter and the arrival of grandchildren. It is as if parents in their later years realize that their future rests with their lineage and over the years overcome their personal objections to the lifestyle or teachings of the Church.

Dan and Mary, in their late fifties, inquired about the Unification Church when their second son joined the movement, their first son having joined earlier. The parents' inquiry led them to join also. This was about six years ago. For several years they continued to live in Tarrytown and to participate in some Church activities as home members. Three years ago they sold their home and moved into the World Mission Center in New York City and took on responsibilities as full-time members. Dan manages an office for one of the Church's foundations while Mary counsels, sometimes cooks, and assists new mothers with care of their newborn.

My husband and I, like the friends we have mentioned, have undergone many of the same transitions that other persons go through in their young and middle adult years. The differences in our experiences are reminders that developmental tasks are not rigidly applicable to everyone and that specific individuals may not fit neatly into the stages.

My young adult life was spent in a religious community of teachers, nurses and social workers. The local religious community, of which I was a member, functioned as a family in many ways. Along with several other members of the group, I also participated in various local and state professional and community organizations. These years culminated in a transition period somewhere in my early thirties during which I experienced internal conflict and a sense that something was amiss in my life. Nevertheless, during this period I was involved in one of the community's education and service institutions for several years.

In 1965 my community asked me to begin graduate study; the overall experience proved valuable and challenging. I learned a great deal about education and also about myself, in part through a death in my family and subsequent counseling. In late 1967 I met the Unification Church and again experienced new life, a deeper sense of fulfillment and a vision for the future. Six months later I left the religious order to become fully involved in the Unification movement, aware that this was the next step in my life of faith. I lived and worked in Washington, D.C. for four years and then in New York for two years. In 1975, my husband and I were married in the 1800 Couples Blessing in Seoul, Korea. This represented another major transition and became a time of much personal growth. For the past eight years have been involved in the opening and development of the Seminary.

My husband, Ernie, retired from the Army in 1969 after twenty years of military service. During that period he served in the United States and in Germany, Japan, Korea and Viet Nam. In Japan, he met and married a Japanese woman in 1953. From 1956 he was very active in the Baptist Church. In 1963, Ernie met the Unification Church in San Francisco and soon became a member. A year later he was sent to Korea where he met Rev. and Mrs. Moon and many of the early members of the Church. Although his wife was initially open to the Church, she later opposed his involvement. They gradually drifted apart and were divorced in 1971. He did pioneer missionary work for the Church and participated in the Day of Hope rallies in the early 1970s. After our marriage in 1975, my husband continued his mission at Belvedere in Tarrytown, New York and in 1977 joined me at the Seminary, also in administration.

In his words:

My early experience in life was narrow and my relationships with others extremely limited, mostly to my own family. Through my first marriage my horizons were broadened tremendously, both socially and in a spiritual way, as I sought more answers to the problems of life and relationships with people I was encountering. I had a relatively successful marriage, a comfortable apartment, and friends, but I felt the need for something more deeply satisfying. This desire led me to a strong religious commitment with the Baptist Church but I continued searching. In 1963, I was introduced to the Unification Church and there found answers to many of my questions. I could see many of the mistakes I had made in my marriage and relationships and also was deeply moved by the rich spiritual experience and love which again expanded my horizons from a personal/family orientation to a more cosmic vision.

Like many other middle aged couples, we have through the years participated in community service, helped take care of aging parents and experienced death in our families. My husband has experienced a divorce and retirement and both of us have second careers. We have redirected our lives, oriented our value systems and experienced growth in personal and professional competence. There has been social growth and a deepening of friendships for Ernie and myself, as well. We have been, and to some extent still are, counselors and teachers to younger persons. There are opportunities to guide and help them -- to support them in many ways including their maintaining or improving relationships with their own parents.

My husband and I and other couples we know find living among younger persons stimulating. We believe that it has kept us younger, more hopeful and positive in our thinking.

To me it seems that the overall experience of middle age is enhanced by involvement in Unificationism, depending on the initiative and creativity of the person involved. In one sense, age does not seem to matter. Much seems to depend upon an individual's self-concept and one's own attitudes about age.

The real benefits, challenges and opportunities far surpass any negative or limiting aspects of experiencing middle age in the Church. Perhaps the greatest of these is the genuine rebirth experience, the deepening of one's life of faith and the vision for a better world. Divine Principle teaches that now is the time to build the Kingdom of Heaven on earth, that we can now restore the world of God's dominion, lost at the time of the Fall. Building the Kingdom is seen not simply as something in the hearts of people but something in the building of which, persons, families and nations are transformed through a step-by-step process of restoration. As I experience and see others experience a quickening of life and growth of character, the coming of the Kingdom of Heaven becomes more real. Many insights in Unification teaching and many requirements in its lifestyle encourage growth, and push one toward the fullest development of one's potential and toward taking responsibility for the larger purpose. Building the Kingdom of Heaven on earth is seen not only as possible but as one's responsibility for the sake of God and of humankind.

I am more and more convinced that young, middle-aged and older persons can together, through mutual love and dedicated effort, transform this world of reality into a shining ideal where everyone will share and partake of its light.

Part of this paper was originally presented at a conference on "The Family and Theology" at the Unification Theological Seminary in Barrytown, NY on May 30, 1981.

1. See Dolores Curran, Family: A Church Challenge for the 80s (Minneapolis: Winston Press, 1980); Gloria Durka and Joanmane Smith, eds., Family Ministry (Minneapolis; Winston Press, 1980); William Pinson, Jr., Families with a Purpose, (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1978); Charles Sell, Family Ministry: The Enrichment of Family Life through the Church (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1981).

2. Joanne Stevenson, Issues and Crises During Middlescence (NY: Appleton Century-Crofts, 1977), p. 14.

3. Ibid., p. 19.

4. Ibid., p. 18.

5. Ibid., p. 25.

6. Ibid., p. 184.

7. Ibid., p. 185.

8. Ibid., p. 190.

9. Ibid., p. 190.

10. Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck, Variations in Value Orientations (Row, Peterson, 1961), adapted for Stevenson, op. cit., reprinted by permission.

11. Stevenson, op. cit., pp. 11-14.

12. Ibid., pp. 185-186. Reprinted by permission.

13. Ibid., p. 137

14. William E. Hulme, Mid-Life Crises (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1980), p. 104.

Ericson, Eric. Identity and the Life Cycle. NY: International Universities Press, 1959.

___. The Life Cycle Completed: A Review. NY: W W Norton, 1982.

Hulme, William E. Mid-Life Crises. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1980.

Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck. Variations in Value Orientations. Row, Peterson, 1961.

Levin-Landheer, Pam. "The Cycle of Development," Transactional Analysis Journal 12, No. 2 (Ap'82) 129-139.

___. Cycles of Power: A Guidebook for the Seven Stages of Life; 1981.

Levinson, Daniel, et al. Seasons of a Man's Life; NY: Ballantine Books, Inc. 1979

Noyce, Gaylord. "The Seasons of a Cleric's Life," The Christian Century 100, No. 4. (2-9 Feb '83), 90-93.

Rubin, Lillian B. Women of a Certain Age; NY: Harper and Row, 1979.

Sheehy, Gail. Passages: Predictable Crises of Adult Life; NY: Bantam Books, Inc., 1977.

Stevenson, Joanne. Issues and Crises in Middlescence; NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1977.