![]()

Unity In Diversity - Essays in religion by members of the faculty of the Unification Theological Seminary - Edited by Henry O. Thompson - 1984

|

|

Unity In Diversity - Essays in religion by members of the faculty of the Unification Theological Seminary - Edited by Henry O. Thompson - 1984 |

One of the most controversial, but least understood, aspects of the Unification Church movement is its opposition to communism. Currently, interplay between the movement and the varied reports from the media and others about its activities, have given this active opposition to communism many confusing faces. Therefore, the issue of the Unification Church and Marxism is extremely important to clarify. Further, it is an issue involving many fundamental aspects of man and his ideological relationship to the world. Therefore, it is useful to present a brief explanation of the Unification counterproposal to Marxism, in a way understandable to the Christian clergyman, layman, or student. In the following paper I will review this topic from three points of view:

1. The precise character of the Unification movement's religious perspective concerning Marxist communism.

2. The nature of the Unification movement's own particular world view.

3. The historical context in which the Unification counterproposal to Marxism emerges as a new ideological alternative for man.

The Unification view hopes to both subsume and surpass the breadth of Marxist comprehension about reality and bring to bear Marxism's ideological strengths by relating them to a concept not of atheism, but of God. Because of the breadth of the issues, an elucidation of the particular view of the Unification movement in relation to Marxism serves generally to clarify many fundamental issues which concern mankind, both communist and religious alike.

Development of the character and work of the Unification movement has been a historical process. In Asian countries, where the movement has long been active, Unification theology and Unification thought have been elucidated in some detail. In Asian nations there has developed a substantial communication between the Unification view and the particular cultural and religious perspectives of others. In the western countries, however, where the Unification movement has only recently become widely established, articulation of the intellectual and ideological position of the Unification view in relation to particular modes of thought, social structure, and ways of understanding, has only begun.

In Europe and America particularly, press and media have reacted to the work of the movement with confusing ambivalence. Although their views vary, they are generally dominated by a characteristic eclecticism which, coupled with commercial interests, make the sensationalist approach most common. As a result, some of the media have given the impression that the work and point of view of the movement in relation to communism is simplistic, reactionary, ill-informed, or fanatical. Similar misrepresentations concerning other areas of the movement's work or thought have tended to disappear quickly with the availability of accurate information and the growing sympathy and participation of scholars, clergy, and others who are socially concerned in the movement's varied work. However, in this trend toward more actual comprehension of the real character and goals of the Unification movement, the clarification of the position concerning communism has been less easily approached. This has seemed to stem from two factors, which are themselves particularly interesting in relation to the subject of western religions and the communist phenomenon:

1. There is a lack of understanding within Christianity of the precise ideological nature of Marxism, and the points on which it is uncompromising. Further, there is little comprehension of the need for Christianity to develop a comprehensive ideology and corresponding ministry of works representing its own ideal, vision and direction.

2. Within the still-remaining western democracies, and especially in the media, recent years have witnessed the growth of a generally naive tendency for extreme self-criticism. This self-criticism has been characterized by deep cynicism concerning the failures and weaknesses of the West. Though such criticism often has good social reason, it lacks a worldwide perspective. Obviously, other forms of government, not just democracies, have basic corruptions and problems. But this self-accusative tendency, often pursued by some of the most knowledgeable and well-meaning, has been counterproductive in numerous areas of politics and culture. In many ways it has cleared the way for gains by world forces opposing the fundamental characteristics of democracy and religion.

Thus, the articulation of the particular view of the worldwide Unification movement in relation to this global ideological situation is not only useful as information for people concerned about the movement itself, but also serves to emphasize one of the movement's major goals. The movement wants to suggest a more balanced and whole perspective concerning democracy, with a clear approach to its inherent value, but still allowing constructive critical analysis of its strengths and weaknesses. Most especially, the Unification view is concerned with the future-of democratic governments and human rights in their religious setting. It seeks to emphasize the dangers which confront this future, from within and without. The Unification view suggests that only with a renewed kind of wisdom and worldwide perspective can the peoples who have democratic and religious roots attain an ideal for man and become the harbingers of new hope for a fully humane future for mankind.

The position of the Unification movement concerning Marxism stems from the global and holistic nature of the movement's views of the world and religion. This position can be characterized as a completely God-centered view. It states clearly that the world was intentioned by God to be His "Kingdom of Heaven on Earth," that is, the visible expression in time and space of God's own perfect nature, expressing and fulfilling in image all the qualities of God: love, harmony, and eternity.

Clearly, the world is not this way. Hence, history is itself God's process of achieving this intended ideal for man. Therefore, if in such a situation an ideology like communism exists, backed by economic, cultural, political, and military powers and is (despite its own purported intention of good and humanistic work) dedicated to the ideas that 1) God does not exist, and 2) morality is not accountable to a higher reality or being, but only to men, power, and competition, such a system represents a dangerous imbalance and error. This mistaken view represents the position of atheistic communism.

The liberation of mankind is actually the function and mission of religions. But in this role they have historically floundered. There has been little testimony to the truth of God carried out in men's living of religion. This failing of religion notwithstanding, it is still the weaknesses of the atheistic position, its 'unreality' in relation to God, that is the fundamental tenet of the Unification position against it. Further, it is exactly the restoration of the original path and position of religion as the vehicle for God's attaining his ideal for man that is the Unification movement's intended mission on earth.

Specifically, the character of dialectical materialism as an ontology, typifies a religious system in itself. On the basis of this ontology, it gives clear definition to all the issues with which religion concerns itself. Since the conclusion of its ideology is that of atheism, it is an anti-religion by nature. The dialectics of Marx do, in fact, understand and comprehend basic aspects of mechanics and relationships in reality but these are used not to make statements about the nature or reality of God, but to prove that God does not exist. Hence, it is the conclusion of the Unification view that though elements of Marxist philosophy and insight are correct, the basic atheistic premises, and more importantly, the flow of logic which concludes with atheism, are fundamentally wrong. The Unification view, on the other hand, which is a comprehensive system embracing both spiritual and material elements, is not limited to either issue.

The historical pattern of communism has been that of accusing religion for failing to solve the problems of the world. Though this argument has a basis in fact, it must not be used to frustrate religion and deflect it as the major path toward the fulfillment of God's ideal for earth. Thus, the position of the Unification movement is twofold:

1. Religion itself must be turned around; it must begin to heal and repair the failure of its history, entering upon a restoration of its original and true mission to serve mankind's future ideal.

2. Opposition to communism is not based on simple historically or politically based antagonisms, but on a clear understanding of the position of materialist atheism in God's world, and comprehension of the critical importance of a fully integrated counterproposal which can fulfill materialist and religionist alike.

The basis of the counterproposal to Marxism is expressed in the theological, philosophical, ideological, scientific, and cultural approaches of the Unification movement, which have been articulated by the Rev. Sun Myung Moon. Fundamental aspects of this viewpoint have been recorded in the book Divine Principle,1 and in Rev. Moon's public and private speeches. Also, beginning recently in Europe and America, these views have begun to be exegeted in commentaries concerning their implications for theology, philosophy, and science.2 Though firmly grounded in existing work both written and oral, the process of more precise definition and elucidation of all areas of theory and application has only begun.3 This is consistent with the history of any comprehensive religious vision as it begins to interface with culture. Christianity, Judaism, and other historical mainstreams of God's work, as well as humanistic philosophies and ideologies, have followed a pattern of the gradual interweaving of their ideological and abstract constructs with the practical applications necessary to culture and society.

The Unification view recognizes a particular pattern in the historical path of religion on the one hand, and the more humanistic or atheistic approaches on the other. To understand the present character of ideologies on the planet in relation to a concept of God and His coming Kingdom, it is of interest to review this concept. First considered will be religion. Historically, religion's approach has often been characterized by otherworldliness, an emphasis usually resulting in a retreat from responsibility to the physical world. Atheistic and humanistic ideologies or philosophies, to the contrary, have been typified by more scientific, world-related structures and organizational patterns. Communism, for instance, has so completely interfaced its ideology with culture that it is often understood by the more ill-informed simply as a socio-economic structure. However, this naive outlook neglects the fact that the entire structure is actually firm in ideology and rooted in certain uncompromising positions, one of which is atheism. The attractiveness of the humanistic work of Marxism has been such that even religious persons have joined the Marxist ranks for the sake of the short term goal of tangible change in the world's social condition. Unfortunately, because of the ideological problem, they have either been misled or are openly willing to leave aside the more basic issue about the worldwide power group for which they inadvertently operate as a peripheral agent. Such a position would not be so dangerous if it were not for the fact that at the base of these groups' support are political and military regimes supplying the finances and direction. This situation only reinforces the need for religions to fill this social gap. It is perhaps fortunate that the lack of accountability to any higher ideal leaves the communist world divided and less effective than it might otherwise be.

The Unification view has articulated the relative strengths and weaknesses of the two basic mainstreams of man's attempts to save himself, the religious and atheistic, and has called these trends 'Hebraism' and 'Hellenism,' respectively. One orientation has historically been toward a concept of God but characterized by failure to respond to the needs of the world; the other has usually been atheistic or agnostic, but dedicated to earthly progress and development. The spirit of one has been vertical and abstract, the other more tangible and concrete. It is the marriage of these two traditions into one God-centered view that will produce the world-serving ideology which can lead to the culmination of human history.

The Unification view is, then, a subsuming vision, encompassing the fulfillment of both of these tendencies and historical mainstreams. Thus the ideological content of the Unification view includes some of the characteristics of dialectical philosophy, but uses this same world view as a statement about the nature of God and His creation. The character, goals, and direction of the Unification view imply the fulfillment of both the horizontal and vertical ideals, resulting in the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth. Thus, it is not surprising that the dimensions of Unification thinking (theology, philosophy, ideology, science, technology, economics, culture, etc.) include many of the structural insights of Hegelian metaphysics on which Marxism was based. But, contrary to the Marxist view, the Unification ideology culminates instead in a God-centered view of creation and an acknowledgment of the democratic and human rights of such religious men under God. Thus, Unification theology as an ideology (the applied aspect of theology or philosophy) has the potential to become a basis for culture into which all areas of endeavor can be integrated, unified upon one God-centered viewpoint. Marxism is the only other such comprehensive view existing in the world. Its present gains worldwide attest to the world's need for such a comprehensive sociological solution for man.4

As an ideology, the Unification view's particular construction of an idea of being or existence (ontology) has been characterized, not as 'dialectical,' but as a concept of 'polarity,'5 'relative aspects,'6 or 'complementarity.'7 It can be expected to undergo a long period of development and exegesis in relation to particular areas of insight:

1. Theology ('Unification Theology,' since the particular view must be applied to the idea of God, scripture, history, and the sociology of religion).

2. Philosophy ('Unification Thought,' since there is particular relevance of the insights to the major areas of philosophy).

3. Science (general commentary, since the structures and models in the Unification ideology are fully applicable to similar operations in scientific philosophy and foundations concepts).

4. The Specific Nature of the Counterproposal to Marxism ("The Theory of Victory Over Communism").8

1. Marxism's Historical Expansion:

Marxist ideologies rely on the present condition of religion as one key to their eventual success. Historically, their writers have pointed to the closed vision and complacency of Christianity, in contrast to their own revolutionary activities. Further, they use this same accusation as a basis for completely undermining public confidence in the social power of religion. Their claim of Christian failure in the West hopes to discredit the Church and allow the work of communist groups to go unopposed, to cast Marxism in the position of representing good against the evils of capitalism. Further, they characterize Christianity as a major contributor to the world's social ills. The behavior of the Western powers, especially in colonial times is an argument Marxists have used again and again against Christianity.

Christianity seems unable to recognize either the threat these characterizations contain, or even more surprisingly, the elements in Judeo-Christianity which could initiate a religiously-oriented social position effective enough to counter the Marxist social revolution. Such a reply, through a completely religious ideology coupled with serving works and action, has not been forthcoming. However, such a theological and social reaction by religions of the West could restore the social and moral force of religion, bolster the remaining Western democracies with citizenry responsible and enlightened enough to maintain these unique constitutional governments, and give future credence to options for mankind characterized by liberty, the morals of religions, and human and civil rights.

2. Marxism's Criticism of Religion

Two thousand years have passed since the death of Jesus, whom Christians acknowledge as the Christ. War, tension, chaos, poverty and disease are still abundantly manifest, even within nations with large Christian populations. The life of the Church and life in society have been dichotomized into 'religious' and 'secular.' Economic, social, political, and scientific concerns have been relegated to the 'secular' category and the Church fails to deal effectively with these. This status quo has even been supported by scripture, alluding only to 'meekness,' 'humility' 'turning the other cheek,' and 'looking to Heaven' as man's station in life, and for a spiritual reward in a life beyond this earth.9

From Marx forward, communists have been all too ready to point out Christianity's failures and use these to discredit the Church and its mission. Such accusations are replete in the works of Marx and Engels, marking the ineffectiveness of religion in relation to massive human ills and problems. The Church is criticized for promoting, under the guise of sanctity, poverty and misery for the lower classes, and of supporting the bourgeoisie in their repression of workers for personal gain.10

In ridding the world of religion, especially Christianity, communism recommends itself as a newer religion, answering "the religious questions of the human soul,"11 and giving meaning to life. Communism is a religion of the state. Marx's ideal was "not religious freedom of conscience but the freedom of conscience from religious superstition."12 Engels, colleague, lifelong personal companion, and translator of Marx, was equally eloquent in deprecating the spiritual life as any answer to the realities of human existence: "A person who makes his whole being, his whole life, a preparation for heaven cannot have the interest in earthly affairs which the state demands of its citizens..,"13 Engels' caricature of a religious man was of one who has striven to achieve the highest goal and failed, settling then for ardent faith instead of accomplishment. The Christian is a weakling, relying on some improbable unseen Supreme Being on whom he can depend as a substitute for the realities of" existence. Along with Engels, Nicholai Lenin joined the deprecative attacks begun by the founding father of his philosophy. He deplored the way religion was used to exploit the masses, saying "Religion is one aspect of the spiritual oppression which falls everywhere upon the masses who are condemned to eternal labor for others by their need and their loneliness Religion is a sort of spiritual brandy in which the slaves of capital drown their image of humanity and their demand for some sort of worthy life."14

The history of communism from the time of its foundation has been controversial in relation to how truly violent its adherents were against religion. Some confusion has resulted from verbal service oft-times paid to religion in public statements and propaganda seeking to influence people of religious nations. Communist delegates have participated in such bodies as the World Council of Churches, and recently with the communist takeover of Vietnam, the government itself has assumed the power of the ordination of priests as one route toward control and weakening of its foundation. However, it is the historical pattern of removal of religious persons and institutions, sustained through massive persecution and even murder behind the borders of communist lands, which has provided contradictory evidence. Obviously, Marxism will take a definite stand against religion once communist rule is attained.15

In theory, communism proposes to answer the problems of society, economics, politics, and science which Christianity has usually left outside the realm of its responsibility. Therefore, communism as a materialistic and revolutionary philosophy continues to initiate conflict and aggression throughout the world. It has become increasingly obvious to those Christians, who analyze the modern world in a faithful and sensitive way, that Christianity can no longer be comfortable in this situation. Rather, it must act from God's side to solve the problems of the earth. However, to accomplish this in a complex modern world, religion must have a philosophical counterproposal which can logically defeat the well-entrenched communist ideology by providing answers for man from religious teachings, especially those of the serving person of Christ. Jesus prayed for the Kingdom of God on earth, and it is the Christian mission to actualize this potential through an expansion of Jesus' kind of teaching to all areas of life, including those called the 'secular.'

3. Christianity's Historical Alternatives (the Social Gospel, Liberation Theology, Christian Radicalism of the 1960s, Black Theology, and the Christian-Marxist Dialogue):

Within Christianity particularly, history has witnessed constant awakenings to the materialist's challenge concerning the role of serving mankind. It is within the context and particular histories of these movements that the work and vision of the Unification movement should be understood. These social awakenings within Christianity have been characterized by Christians' efforts to develop the social reality attested to by their faith. It is impossible to review all of these, but the following are of interest because they represent distinct aspects of this effort which has continued to occur within Christianity: the Social Gospel, Liberation theology, Christian radicalism of the 1960s, Black theology, and the Christian-Marxist dialogue. They can be characterized briefly in relation to their role as precursors to a view of worldwide religious restoration.

Advocating the interdependence or all aspects of society, the Social Gospel movement maintained that humanity, rich and poor, rose and fell together. It was a holistic view of the application of religion. Richard T. Ely, in his doctrine of "social solidarity" advocated full religious responsibility to social reform through the influencing of social legislation and supplying of moral energy and example through the churches. Walter Rauschenbusch, in his Theology of the Social Gospel, articulated the new meaning of socially conscious Christianity in the already familiar texts of Biblical scripture. The movement, with the outspoken support of such literary geniuses as Matthew Arnold, became the major source of humanitarian concern during the process of Western industrialization. But the movement was relatively short-lived, weakened by lack of a concise statement of ideology or organization, and by an over-reliance on the belief that moral energy itself was enough to effect lasting social change.16

Influences of the Social Gospel movement remained apparent throughout the early twentieth century, but it was not until new social confrontations challenged the stability of Western nations that new movements, centered on the social implications of Jesus' teachings, appeared and defined still new directions in this restorative trend.

Out of the relation of sensitive Christians to the poor and disenfranchised of class-ridden Latin American countries came the movement of Liberation theology. Strongly influenced by the Marxian ideals of collectivism and mutual help, it reacted as a vector of change for the oppressed masses.17 Its leaders, primarily Catholic, developed a mystical and practical blend of faith hoping to forge a new society in which "the worker is not subordinated to the owner as a means of production but in which the assumption of social responsibility for political affairs will include social responsibility for real liberty and will lead to the emergence of a new social consciousness."18

North of the Latin American dilemma came the confrontation in the United States concerning the civil rights of minorities and the morality of undeclared war. The Church again came to the forefront, though in an ambivalent posture. Sensitivity to the element of Marxism was evident. Fr. David Kirk, in his best-selling Quotations from Chairman Jesus re-emphasized the proper spokesman for the oppressed and the people of hope. The movements which became controversially known as the "Underground Church" reacted against the authority of Church institutions to repress their desire for social action.19 These movements, again, tended to disappear as the issues they confronted passed from the public mind, but the issue which did remain was the problem of civil rights. This time it was the Protestants in the persons of the Baptists and African Methodists who provided the leadership for the movement that led to political enfranchisement, at least in law, for American minorities. Martin Luther King became the leader of a host of new American public figures, and from another section of world religions, the Black Muslim movement rose from the jails and streets to set another new standard of hope and constructive contribution for the oppressed. The action of these movements on the society was generally a favorable one. The religious influence of the church gave the moderating tone and influence to an otherwise dangerously violent potential. Theologians of the new groups echoed the standards of Jesus, of forgiveness, of repentance, and of reconciliation.20

It is on the stage of this history of active movement toward a full religious life in western societies that the Unification movement has emerged. It has its own roots in a history of oppression in Asia, and its membership is made up of people bridging gaps created by hatred and war. Anchored firmly in the Christianity that was exported to the East by Christian evangelicalism, it returns with a modern revelation of the character of the world and the future of world religions.

The dialectics of Marxist communism deal with the same issues as religion, but claim to use a methodology compatible with modern science. From the religious viewpoint it is of critical interest whether the ontology itself is defective, and hence prevents Marxism from claiming a methodology that is genuinely scientific.

As is widely known, the communist philosophy treats all things as objective and made of matter alone. It also asserts that all things contain contradictory elements. All things change, move, and develop not through the interrelating of complementarity or relative aspects, but through the struggle of contradictory elements against each other. The fundamental contradiction is characterized as mutual needing, on the one hand, and mutual repulsion on the other. Need determines the quality of unity; repulsion characterizes the struggle. Societies are overthrown and replaced by new ones through conflict and struggle because the relationship between the fundamental element in things is most basically struggle, not mutual assistance or interdependence.

According to this Marxist ontology, entities are not a union of relative aspects in harmony, or of paired relations in a mutual interdependence of love and freedom, but acquire internal or external unity only temporarily through the process of negation, the winning of one side over the other. This particular dialectical outlook had its origin in Hegel's philosophy. In his Logic (variously published; this paper references 1892, lot. cit.), Hegel developed a theory of essence stating contradiction not simply as opposition, but as sharp opposition involving complete denial or repulsion of one of the aspects. He implied complete denial and repulsion, not a common purpose or common interdependence.21 It is in Hegel's notion of thorough negation, that the Marxists find the basis for their negative statement about the nature of process.

Hegel's concepts were used first by the mechanistic materialists and later by the dialectical materialists to develop a logic in which the problem of first cause, the problem of the existence of a God, could be ruled out a priori. Not only could God be ruled out a priori, but He must be. Only this liberating denial of God, a first cause, could allow a logic based on the supremacy of matter alone. Engels, in his book Dialectics of Nature (1846) cited many natural phenomena in mathematics, astronomy, physics, biology, and dynamics as examples of how the universe is characterized by material and processes based on the principle of contradiction. In all cases, Engels invokes the perception of repelling or negative relations to explain his observations, rather than a view of affirmation, coordination, or mutual harmony. Though it is true that the sophistication of these arguments has changed with time, the general lack of an affirmative tone has not.22

To the Christian, who is used to a concept of sin as the reason for man's earthly dereliction, it may seem strange that the dialectical materialists never considered the possibility they were unnecessarily extending to the whole universe the type of contradiction and internal confusion they observed in man. The negative values, implicit in the ontological view given by the Marxists, were developed in the materialist system to describe the relationships between people, determine the value of the individual, legitimize conforming to the state, relate economic and social evolution, and, even more recently, create a repressive psychiatry.23 The moral bias of the negative tone is great, and it is here that the element of negation characteristic of Marxism has affected society the most. The path of Marxist governments toward totalitarian dictatorship, characteristically without regard for human and individual rights, has been the usual social result of nearly all Marxist acquisitions of power.24

Regarding the possible existence of a spiritual reality, the conclusions of Marx, Engels, and their colleagues, are indicated by their denial of religion. According to Marxism there is neither God nor soul. There is spirit, but this spirit is an emergent quality coming from man's speculative ability and consciousness, which exist only as they emanate from the physical brain. To the Marxist, the emergent quality mistaken by the religious as eternal soul is not even a product of the brain; then it could exist independently. Rather, it is an expression of function, an artifact of man's observation. Matter is the subjective component here. Students of the history of the development of Marxism, through Hegel, Feuerbach, Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin, are familiar with the efforts to which dialectical materialism has gone to exclude any possibility of God as a first cause.25 Allowing the spiritual to be seen simply as an artifact of man's observation of the function of brain tissue is to the Marxist one of the most liberating insights -- it frees him from an oppressive allegiance to a higher authority.

Dialectical materialism takes on its full development in relation to the consideration of how matter participates in motility and historicity. Hence, much of Marxism deals with dynamics in material, and the processes it delineates as man's experience of history. Originally, the precursors to the dialectical materialists, the mechanistic materialists, distinguished between movement and matter. They regarded matter as static until it was affected by some outside force. But inherent to mechanistic materialism, as with idealism, was the problem of first cause, the problem of the existence of God. It was the dialectical materialists who perfected the developed dialectical theory that movement was not only just an attribute of matter, but its very mode of existence. The solution of the Marxists was: there cannot be matter without movement, or vice-versa. Thus, for the dialectical materialist, the way to solve the problem of first cause was to attribute movement to matter. Otherwise, it must originate somewhere. If it originates somewhere, there might be first cause, and this first cause is what man has experienced as "God." Dialectical materialism had to deny mechanistic materialism precisely on this point, because unless one reverses the logic, completely allowing matter to be the subjective quality of existence, one admits, de facto, that God might exist. Instead, movement is the changing process within matter itself. It has self-causation. The origin of this movement is the unity and struggle of the contradictory elements of the dialectic. All matter, then, has the dialectical interaction of two contradictory elements, continuously accepting and rejecting each other. It has no origin; rather, it relates to process through this relation of opposites, "thesis" and "antithesis," which resolve themselves through negation and struggle to some synthesis.

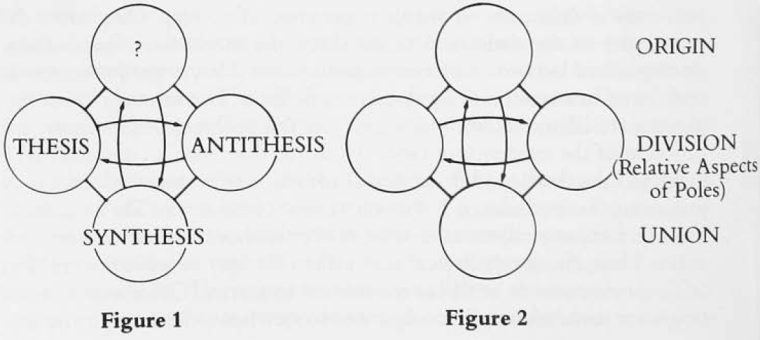

For Marxism, this insight becomes the classic model of what the Unification view would consider a partial Quadruple, the "Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis" (Figure 1). Because Marxism is not concerned with cause, it has not considered its model as Four Position in nature. A Four Position model centers the relation of the "thesis" and "antithesis" on something. It is only an embracement of cause, centering the relative components on an origin or purpose, that makes an actual Quadruple, or what in Unification terminology is often called a "Four Position Foundation." In the actual Quadruple, or Four Position Foundation, the uniting of the components (negatively called by Marxism "thesis" and "antithesis," by Unificationism "relative aspects" or "polarities"), takes place because their activity is centered on a mutually harmonious purpose (Figure 2).

The problems which have developed in Marxism because of this lack of purpose or ideal upon which they can center the "thesis" and "antithesis," which they instead see as struggling in antagonism for some synthesis through competition, negation, and exclusion, have been tremendous. These cannot be explained here in detail, because they have been developed through a long historical process in Marxian logic. But, a crucial moral problem develops from their logic which can be reviewed as follows:

All matter exists in time and space. Hence, each entity participates both in "practice" (pursuing what it does) and in "recognition" (being acknowledged by others). To the Marxists, because of the negative logic, and the concept of motion as the nature of matter, practice (e.g. work), not recognition (e.g. rights), is what justifies an individual. This becomes coupled with their idea that the value of the individual is not primary, but secondary in relation to its participation in the whole. Of course, the state and ruling party determine what the value or standard of the whole is. This philosophy was perhaps an honest effort to resolve the conflict between the needs of individuals and the purpose of the whole. But, the imprisonment of the opponents of Marxist regimes, the labeling of the religious and other dissidents as psychologically ill, and the restriction of freedom of expression in the arts and letters, have been outgrowths of the ideology as it is applied. Engels, in his Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, expresses what is probably typical of the search for a balance between individuals and the whole. Written at a time when the world was nearly everywhere oppressive, Engels uses his observations as an accusation against the metaphysicians and the religious:

the metaphysical mode of thought... in the contemplation of individual things, forgets the connection between them.26

This was not inaccurate. However, it creates vicious consequences in a system that places the prime importance on the role of the individual in practice as defined by the whole (the state). It also considers the human being to be matter that has been conditioned by the environment. This view of "conditioning" results from the particular evolutionary viewpoint of the Marxists. Animals have evolved from lowest to highest; if instinct in animals is the result of programming to the environment by adaptation (through mutation and natural selection) and if the instinct in animals corresponds to the spirit in man, man must take on his spirit in relation to his conditioning. Hence, not only is man simply the result of conditioning, he must be properly conditioned. Further, he must be conditioned by the atheistic Marxist society, not by the religious notion that he has some inherent freedom in himself.

It is this view of practice that becomes the theory of action, labor, and production characteristic of modern Marxism. Man takes on his role as the architect and conscience of matter, and only with the proper ideology can he program himself in the proper way. Man has evolved through a long progression to discover this proper way of conditioning himself; man is to find his destiny in this discovery through the attainment of the materialistic dialectical vision. At this point, utilizing the proper ideology to program himself, man can enter a Utopian era. By revolution he can establish himself with a culture truly recognizing human nature and humanity's place in reality.

In Marxist theory, history develops through the repetition of three stages -- thesis, antithesis, and synthesis -- and is finally resolved through the process of negation and struggle. The world is not unfolding based on purpose or Divine Providence. This is only true in the Unification version of the dialectic.

Among contemporary theologians, Paul Tillich has articulated the Trinity in dialectical form in his Systematic Theology (1966). For him, the doctrine of the Trinity is neither irrational nor paradoxical. Rather, it is dialectical. The trinitarian symbols are dialectical, reflecting the dialectics of life, namely, the movement of separation and reunion. If this dialectical concept of the Trinity is meant as a description of a real process, it is to Tillich a precise description of all life processes. Obviously this is a basis for a view of God compatible with nature, unifying those things which were formerly divided into the "spiritual" and "natural".27

According to Tillich, trinity is the innate answer to man's situation. He based his belief on the notion of three natural needs of mankind mirrored in the developments of revelation history. First, there is the tension between the concrete elements in man's life and those in which he experiences the Absolute. Second, man is inevitably relating his life to a "divine ground" of being. Third, man experiences religious reality as creative power, salvific love, and transforming ecstasy. Man and his God develop their relation (finally, union) under the condition of their existential separation. It is this independence of being which makes love possible, as has been recognized in the traditional notion of trinity. This is especially true in the connotations surrounding the term "hypostasis." For Tillich, the three concepts of God as "Father," "Son," and "Holy Spirit" are essentially derived from the three basic ontological characteristics of man. The first two persons of the Trinity, God the "Father" and God the "Son," correspond to what Tillich calls an inner, intangible "ground" and an external substantiating "form," respectively. This means that there has to be a vertical dialectic of (1) a nature and character outside space and time ("Father") relating to (2) a form of image of the character within the dimensions of space and time ("Son"). Finite man and his relationship to God can be compared to the idea of God Immanent and God Transcendent, e. g. we know God by His manifestation or substantiation on earth, Jesus the Christ.28 The third Person of the Trinity is established after the concrete development of the relationship between "Father" and "Son." As Jesus said, "If I do not go away [to the Father], the Counselor [the Holy Spirit] cannot come to you" (John 16:7, RSV). We can understand, then, God the "Father" (Transcendent) and God the "Son" (Immanent) as two necessary aspects of the Triune God. This can be cast as a complementary dialectical relationship between two relative aspects and a third -- their unity. In this light, we can understand more clearly a similar impression of St. Paul, in Ephesians, where he speaks of the persons of God as a unity bound together in the perfect love of the Holy Spirit.

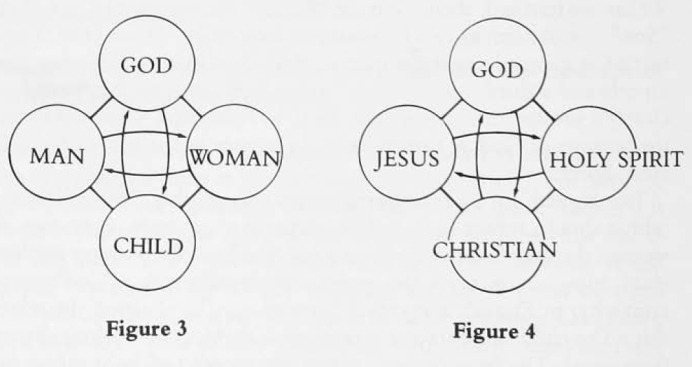

This model can be transferred to the relationships within the world which should reflect God as His image. For example, as a man and a woman (husband and wife) form a bond of love, their union produces a child. Most interestingly, this aspect of their unity reflects God's image in creativity; in English it is called "procreation," indicating the relationship. The child becomes the most personal object of the love shared by the parents. The "procreation" of the third person of the family expands the dimension of the family unit and reflects the dual natures of husband and wife in one entity. Through this three-dimensional relationship, three types of love are given to the child, that of Father, Mother, and Parents. St. Paul says "... let each one of you love his wife as himself and let the wife see that she respects her husband" (Eph. 5:33 RSV) and "Children, obey your parents in the Lord, for it is right. "Honor your father and mother..." (Eph.6T-2RSV). At the center of this relationship in the Christian concept of marriage is God, whose image people reflect. Through the marital relationship, man and woman, as co-equal parents, form the complete image of God (Gen. 1:27) with God as their center. The child, as the image of God and image of the Parents, completes the unit (Figure 3). Similarly, when the Christian, through the inspiration of the Holy Spirit accepts Jesus as Savior, he also becomes the mystical or "spiritual" child of Jesus and the Holy Spirit, thus forming the mystical family of God (Figure 4). With such a succinct insight available into the nature of God and man, using the dialectical understanding and the Quadruple model, it is hard to imagine what value these paramount aspects of life can have to the atheist, when there is no center or direction on which they are purposed. A unique contribution of the Unification ideology is its unifying of these concepts within a precise understanding of how all of reality is structured. The religious person understands, then, in a way compatible with all experiences of life, the meaning of these most intimate and personal things.

Central topics in the dialectical materialist's idea of being include theories of interrelationship, the existence of contradiction, the process of negation and the dynamics of development. These can serve as a basis for a fundamental critique and counterproposal from the Unification view. To give more of an idea of the nature of these Marxist concepts and their potential restatement from a religious point of view, one that includes the existence of God, I will review these theories below. Further, since it is helpful to use examples in clarifying many of these ideas I will consistently use the analogy, already introduced, of the relationships within the human family.

1. The Theory of Interrelationships

Without exception, things in the material world do not exist in isolation. Rather, they participate in complex webs of mutual interconnections and relationships. This is corroborated by modern scientific knowledge. Recognizing this, the Marxist dialectic makes the existence of mutual relationships and interconnections in nature a fundamental statement. But because the dialectic is exclusively materialist and thus atheistic, it cannot deal with the problem of an original cause, it says nothing about why such relationships exist or toward what ideal or state they may be striving. In fact, because of the nature of the ideology, the dialectical materialist cannot even make this his concern. Since matter is placed as the inherent subjective cause in all things, the materialist can only explain matter centering on his logic which maintains a concept of process without the problem of first cause. In the dialectic, the problem of motive, reason, and cause in and beneath the existence of things and their processes is closed. Without the concept of original cause, these concepts of being and existence treat only results and resultant processes. Interest in pursuing the basic source is closed. This aspect of dialectical materialism is one critical point of error. After all, it is more scientific to assume God may or may not exist than to assume that He does not. When constructing a world view, the margin of error between the extremes is quite great!

A God-centered point of view considers why mutual relationships exist and come into existence. To develop this insight, we begin with the assertion that the universe is an organic whole, unified and directed by purpose. From this insight, religion perceives mutuality of relationships, harmony, development, ideal, direction, and purpose. Religion claims that without a purposeful principle inherently operative throughout the universe and recognized by man as the center of his own being, man cannot have a concept of true value, morality, or love.

In the Unification Principle we consider this issue of mutuality from the point of view of how mutual relationships between all things involve the "give" and "take" interaction of "subject" and "object." According to our argument, fundamentally equal but complementary and mutually coactive subject and object parts attain a unity and completed identity and purpose through their participation in the motion of harmony and mutual care. Thus, from the smallest relations of protons and electrons in atoms to the complex structures and cycles of the celestial bodies, everything exists in magnitudes of these relationships of give and take in subject and object pairs. This universe is thus a gigantic organism composed of myriad relationships sharing give and take action vertically and horizontally. It is one universal body of life directed with a common purpose. This common purpose originates from the reality of God. Every creature participates as part of a common goal and ideal, with its ultimate ideal being the expression of God's own image. This image of harmony, mutuality, and all that is affirmative, is expressed first in symbol (in fundamental relations inherently functioning in this principle), but ultimately it is expressed in man, where God's unique characteristics of freedom, creativity, and love are incarnated. The material things of the universe have mutual interrelationships, harmony, order, and principle because they exist as the base to fulfill God's ultimate purpose: His incarnation in men and women.

2. The Theory of Contradiction and Negation (Thesis-Antithesis-Synthesis)

In the Marxist dialectic, process is accomplished through the complementary struggle between elements that are in contradiction. All things and their modes of development are necessarily composed of two contradictory aspects; one is affirmative, the other, negative. For a time, the two contradictory elements develop, participating in two relative dynamics, unity and struggle, attraction and repulsion. They continue to develop until they reach a critical stage when culmination of the process forces a synthesis (called the "negation of the negation"). This makes an end to the struggle for that period of development. The synthesis is neither affirmative, nor negating; rather, it is an entirely new thing. In it, however, the characteristics of affirmation and negation remain intact. This synthesis, the new thing resulting from the negation of the negation, the resolution of struggle between attraction and repulsion, includes within itself a new resultant opposing element. This element then begins to negate the synthesis. The new thing, thus, has its own element in opposition to the synthesis and because of this, new conflict and struggle is initiated. This is again consummated by a new, but higher level, negation of the negation. Therefore, without end, the two opposing, contradictory elements continually repeat this process of conflict and struggle toward unity and the pathway of this process continues forever.

a. The Concept of Contradiction:

As stated before, in the Marxist understanding of the dialectic the two fundamentally opposing elements need each other on the one hand, and are repulsive to each other on the other. Their relationship of mutual need is their "union;" their relation of mutual repulsion is "struggle." All things have within themselves these two contradictory elements, seeking unity yet opposing each other. Thus, through unity and struggle all process occurs. The dialectical examples for this idea of being include such things as plus and minus in mathematics, action and reaction in mechanics, positive and negative charges in physics, combination and separation in chemistry, and class struggle in sociology With the exception of the last item, these examples come from the natural sciences and are relatively simple and observable concepts. Also, in all cases but the last, it is just as easy to suggest that a unity exists between the elements through their inherent complementarity and harmony, rather than a struggle. But this option is not entertained by the Marxists. Although there is an ideal of oneness, it is at the same time identical with the process of antagonism and struggle. The Marxist makes this erroneous identification because he has not rightly underscored the metaphysical aspects of matter from some original static or dynamic point. Rather, since he sees everything in relation to a faulty view of change and development -- a mechanical and materialist one -- he always sees conflict and struggle in the two uniting things.

From the Unification view one can agree that the concept of contradiction applies to much of the process of social change. Social development has nearly always been characterized by struggle. But the other relations are not as easily assumed to represent the dialectical position, except as they might follow from our observation of struggle in human nature. For example, the birth of a child can hardly be seen as a struggle between the fetus and the mother; rather, after a regular period of maturation, the stability of tissues in the mother's womb discontinues in response to certain hormonal action. The hormonal action is itself initiated as response to indicators released by the process of maturation. The mother's tissues then respond, allowing the birth of the child. The tissues of the mother expelled at birth cannot be viewed as tissues that have been overcome, but tissues that have fulfilled their purpose and no longer have a meaningful existence. In an even more simple example, in natural science, we would be hard pressed to see struggle in the neutralization of electrical charges or the relation of proton and electron in the atom.

According to the Unification view, development in nature does not take place through struggle, but through a unity achieved by mutuality and complementarity of relationships. These are typified by harmony, correspondence, and cooperation. Struggle is secondary. The Unification view treats the problem of man as a very unique problem, as should be expected since as a religious view it entertains the notion of the significance of man's spiritual life. Man's history is his history with God, a history which represents man's inability to achieve the ideal of harmony and unity. For God, man (invested with the very potentials that allow his deviance) was and is to be the culminating illustration of God's own nature. The struggle of man is not one in a blind universe typified by fundamental elements of contradiction and antagonism. Instead, it is a long journey back to an understanding of how mutuality and unity are achieved, an understanding of how man can use his freedom and creativity to share his life with God and be a co-creator with Him.

b. The Concept of Negation:

Marxists believe that any transformation from one level to another involves opposing action. Hence, the synthesis or resolution of any struggle contains its own opposing element. Negation in the dialectic is the concept used to explain the process of development in all things: through negation the previous state is sublated, with its positive aspect preserved and embraced in the negation. Thus, negation takes place only in form, while content is actually preserved. Hence, concerning the tissue of the womb in the mother and the position of the child, the fetus maintains unity for a time with the antagonistic element of the mother's womb, but later is negated by the child and attains the synthesis of birth. The child, which is the negation of the fetus, does not in this case abandon the fetus; rather, it is only a further development of the fetus. Thus, there is neither reconciliation nor abandonment, but a developmental negation leading to preservation through sublation. Negation is an idea that is much like the idea of contradiction: the process of negation takes place through the struggle of conflicting things. The culmination of the struggle does not imply lasting peace or harmony.

The Unification view considers the matter from another point of view. The things in God's world are basically complementary in nature, and they develop through the mutual and motion-initiating relationship of subject and object. The action of give and take between subject and object ceaselessly and necessarily operates. It is called the "Law of Give and Take." Through the action of give and take, all existence, multiplication, and action is initiated and sustained. It is not an action of opposition and conflict but one of harmony, cooperation, and correspondence. Thus, unity in development is continuous. Through development, things change, but within a basic context of harmonious give and take.

Within the problem of sin and its origin, man would also have developed completely in this way Man's deviant state came about because he, as the element in the position of the object, did not define his identity in relation to co-responsiveness and mutuality with the subject, God. Instead he sought to establish this relationship with himself. Mistaking the nature of his freedom and creativity, he has foolishly tried to occupy the subject position and, hence, the relationship of give and take has become one of conflict and struggle. Atheism tries to perpetuate this error. Consequently, history has been a process of struggle between the original principle of subject and object inherent in man, but which is only accessible through the proper use of free will, and the element of contradiction that man himself introduced through his failure to correctly understand his covenantal position with God and with other men. Hence, even history reflects this contradiction of inherent and introduced standards; there are times of peace, prosperity, and harmony, and times of war and conflict. Therefore, the concept of good and evil enters the Unification view. Evil is the tendency toward disorder in relation to the original principle or harmony (called in Christianity the "diabolical" tendency); good is the tendency toward the ideal of the original principle of harmony, mutuality and cooperation. History can be viewed as the long struggle of man from contradiction to the ideal, not simply, as in the Marxist view, one of class struggle, the succession of power groups, and the culmination of production cycles. Patterns in history exist, but it will be demonstrated in the following sections that they are not described by the Marxists adequately.

3. The Theory of Progress

In the dialectic, all process is the result of contradiction. In the contradiction there is struggle, conflict and opposition. Where these occur, process and development occur. It is not a development characterized by unity and harmony; rather, it is one in which quantitative increase is interrupted by abrupt qualitative change achieved through a clash, after which a higher state begins. In this fashion progress through negation is able to move from the lower to the higher.

a. Quantitative and Qualitative Change:

Gradual development does not go on continuously, but is interrupted by sudden changes through which a new level is achieved. Again, the example of the birth of a child might serve as an illustration. This phenomenon is called the "Transition from Quantitative to Qualitative Change." Qualitative change takes place on the base of quantitative change. The nature of the qualitative change is the one of negation, that is, one element or group overcomes the other. For instance, in Marxism this is often seen as the relationship of the ruler and the ruled. In the dialectic, one of the contradictory, opposing elements is considered to be superior; the other, inferior. Hence, process involves one party subordinating itself to the other, one gaining power over the other. At some point in time, however, these relationships characteristically go through a reversal. For instance, the child will eventually dominate his aging parents. Thus, in Marxism, new contradictions are always developing as the characteristic of process and progress. The child of one day will move on to fulfill its own relations of negation through having his own child. The qualitative change is characterized by this kind of reversal.

Obviously, it is possible to see this same content in another way. Certainly there is a relation between qualitative and quantitative change. Nearly all process expressing abrupt change: boiling of water, freezing of water, eruption of volcanoes, initiation of avalanches, etc., also show gradual change. Other natural processes are characterized completely by gradual transition -- seasons, growth, the piling of objects, and so on. But more importantly, the entire structure of this concept can be re-examined in the light of the Unification view.

For the Unification view, all process and change result from the give and take action of a subject and object. A basic problem in Marxism is that it is unable to grasp a fundamental complementary relationship between quantitative and qualitative change. It is limited to having one lead to the other. A deeper concept of progress also admits the case in which there is a simultaneity and mutuality of qualitative and quantitative change. The basis for this insight is inherent in the Unification Principle's concept of Sung Sang ("Internal Character") and Hyung Sang ("External Form"). The Hyung Sang of things refers to their material properties: shape, structure, size, and the like. Sung Sang refers to the quality, character, or function of things. During development, Hyung Sang does not change to Sung Sang, or vice versa, although they can affect each other. Both of these are relative aspects for a complementary relationship. They exist simultaneously. They co-facilitate progress. Thus, the birth of a child also involves the simultaneous fulfillment of the purpose of the tissues of the womb. Also the attainment of the form of the child (quantitative) and the character of "child" (qualitative) occur together. Also, the purpose of the mother in having a child and the purpose of the child in living his life can be fulfilled simultaneously. These are relative aspects of one thing, existing in a dialectic of polarity.

Both cause and effect in the physical world (the world of effect) exist as manifested effects of prototypes which exist simultaneously in the complementary world of cause. The complementary world of cause is the larger Sung Sang, the invisible dimension called in the Unification view of God the "Inner Sung Sang and Hyung Sang" of God. The Sung Sang and Hyung Sang that exist in all the physical processes are called in the Unification view the "Outer Sung Sang and Hyung Sang." In the Unification understanding of God there is a dynamic concept of interrelated levels of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang. The Inner Sung Sang and Hyung Sang existed before the outer Sung Sang and Hyung Sang, but they now exist simultaneously with them and they all affect one another. In the general relationship of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang, the Sung Sang and Hyung Sang of the invisible world of God can also be said to be prior to the Sung Sang and Hyung Sang of the physical world in the complementary sense that it is the subjective position by nature of its being eternal. Sung Sang and Hyung Sang entirely of the physical world is transitory. Thus, Sung Sang and Hyung Sang coexist simultaneously and Sung Sang is revealed through Hyung Sang. Therefore, for something to exist in reality, the simultaneous action of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang are required.29

In summary, this marriage of cause and effect in such a universal cosmic model as the Unification view allows for a more complete insight about the nature of process in the physical world. It is called in Unification thought "the Law of the Change of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang." There is not a question of dominance in this concept as in the inferior and superior, or the ruler and the ruled, only the concept of process through complementarity. This is the relationship of subject and object, and their give and take action in the motion of harmony, co-equality, co-creation, and co-potentiality. There cannot be dominance in this model because both the Sung Sang and Hyung Sang are relative aspects of one thing centered on purpose. Since the relation of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang, that is, subject and object, is one of mutuality, progress takes place by the give and take, which involves exchange or position -- circular motion. Since this continual exchange of position in the relationship is the unity of harmony, and this is the source of development, one cannot conclude that qualitative change comes about through the type of sudden reversal or abrupt change purported by the Marxists. The changes in development are primarily harmonious, gradual, and peaceful in quantity and quality although they produce distinguishable stages of development along the way. They do not inherently harbor contradiction, struggle, negation, suddenness, and destruction. Rather, these attributes are the result of the already existing or created disorder caused by the deviance man has introduced into this life through his conduct.

b. The Forward Tendency of Progress:

According to the dialectical materialist, contradiction is inherent in process, and this necessarily initiates movement in certain directions. This movement is viewed as forward movement, in other words, progress. For instance, the child grows from a fertilized egg through the various cleavage stages, the stages of embryonic development, and finally becomes a fully mature newborn child. Also, the dialectic recognizes non-directed movement and random or repetitive movement. Originally, Hegel, a mechanical idealist, stated that movement was not inherent in things, but that spirit or a consciousness operates in the universe giving the natural movements their direction. But, as mentioned before, dialectical materialism went farther and concluded that spirit is simply a product of material, and not an independent one at that. Hence, the dialectical materialists hold that there must be a difference between forward and repetitious movement. For instance, in some developmental pathways, when the essential cause of quantitative change is within the process itself and consistent, movement will obviously be of the progressive or forward kind. But, oppositely, another kind of direction, repetitious movement, is caused when the force initiating the change is only an external one. From the example, the development from embryo to fetus and child would represent an internally directed movement, which is called progress. The unnatural external inducement of birth by drugs, however, illustrates a repetitious movement, with direction being only a repeatable reaction of the womb tissues to the effect of the drugs themselves.

This dichotomy concerning kinds of movement seems plausible, but historically has caused difficulty. It is unable to deal with how forward and directional movement can occur when the essential cause of quantitative change exists within the changing process itself. For instance, it is not entirely accurate to say that the drug-induced birth only follows from the action of the drug itself. Rather, it results from a series of pathways of response within the chemistry of the mother after the initial reaction to the drug. Without the inherent internal pathway, facilitated by the nature of the chemistry of the mother, the drug would have only a small and isolated effect. Further, the natural birth is actually the reaction to a constellation of stimuli, some within, some without, and some inherently built into the organism through thousands of years of environmental and genetic development.

How, then, is this problem more clearly resolved through the more comprehensive Unification view? Simply, it is enlightened by the relation of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang. The cosmic model of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang, the invisible dimension of God and the "spiritual" in direct and simultaneous complement with the physical and finite dimension of man and creation, allows a complete understanding of directional process in the physical world. Admittedly, the concept of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang is not a simple one to grasp, but it is a crucial concept in the Unification view. To simplify the concept for Unification teaching purposes, often the term "life force" or "universal prime force" has been adopted to indicate the resultant directive force from the successive levels of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang which proceed from God Himself. But it must be remembered that this "life force"31 or "universal prime force"32 is not an existent entity in itself as is implied by similar uses of the term in other philosophies.33 In the Unification view it is not a separate entity invoked as a cause. Rather, it is one of the resultant components of the Origin-Division-Union resolution (the Unification view's God-centered alternative to the thesis-antithesis-synthesis of Marxism) in the relations of successive Sung Sang and Hyung Sang from God's initiating point. As stated earlier in the brief discussion of the Four Position Foundation and the three-stage process of its achievement through Origin, Division, and Union, prime force is the union of the complementary aspects centering on purpose. The concept of resultant "prime force" is related to the Unification view's concept of Eogos.34 Thus, the Unification view would not subscribe to the materialist idea that the force of direction in things is inherent in material. Instead, it exists as a part of the relationship of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang. Concerning the example of an embryo, the Unification view would not look to the material of the embryo to find the directive force apparent in its life. The directive force is seen within the cosmic view, including the position of the initiating reality of God. This is why the Unification view is able to speak of "creation" though not exactly with the same meaning that "creationism" has often had -- a simplistic idea of some kind of magic performed by an outside omnipotent being. Rather, the Unification view would see "creation" within the model of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang as has been here expressed.

c. The Spiral Concept of History:

The Marxist idea of progress in the dialectic also includes the concept of the negation of the negation. It is said that any given thing which during development is doubly negated has attained synthesis and a higher state of existence. Importantly, this synthesis, attained through double negation, also completes a cycle. This is how the oft-seen cycles in nature are explained. For instance, negation of a fetus is a new-born child, this child grows up and produces a fetus, and this is a cycle.

From this view of cycles, the communists recognize stages of society which they claim must be repeated. These predict the coming of the worldwide communist state. Society began with the primitive communal form, and has progressed through slave-holding societies, feudalism and capitalism, which will be followed by socialism. Each of these stages except the first is a repetition of an earlier stage at a higher level. The cycles of history are spiral in nature. They are characterized by repetition of stages at higher levels of comprehensiveness and development. Thus the original primitive communal society is thought to predict the eventual Utopian communist state: the class societies that negated the original classless society, will be negated in turn by the coming classless society.

Like the Unification view, communism affirms the reality of the circular movement resulting from the interaction of complementary or dialectical elements and their resolution through the Origin-Division-Union. But why such movement occurs, or how it is significant in the sense of direction or purpose is not a question that can be approached using communist philosophy. In other words, the materialists cannot clarify why the negation of the negation necessarily takes a circular pattern.

Because of its comprehension of the relation of cause and effect in the cosmic model of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang, the Unification view has a more comprehensive idea of circular movement (called "the Law of Circular Movement"). According to the Unification view all things are created by the law of resemblance; they are created in the polarity of object and subject and resemble the polarity and perpetuity of God. To have perpetuity, all things must circulate through give and take relationships because this is the pattern of sustenance and eternity. Briefly, though the concept is much more complex, God's perpetuity itself is maintained by Himself being centered in circulating polarity upon his own absolute nature called "heart" in Unification theology.35 Thus, if this is the nature of the Sung Sang of God and the Sung Sang and Hyung Sang relations within this Sung Sang, all corresponding things in the Hyung Sang world of the physical creation (and their Sung Sang and Hyung Sang relations) revolve not only in space but in time. Hence creation illustrates cyclic patterns of generations, periodicity, parallelism, and so on. As the things of creation move through time, they are created to exhibit higher levels of completeness. Such development can be comprehended without any reference to the negation of the negation. Rather this can be understood as from the action of give and take. The shifting and growing is one of progress towards the ideal.

It is because of the problem of sin that man's progress has not fallen within the natural movements inherent to the patterns God created. Instead, man's misuse of his freedom and creativity, his "fallen" nature, have led him to deviate from the actual principle of creation. History has been a long arduous path of restoration through successive stages based upon God's continual sacrifice and love for man. In this history, God has been assisted by the work of those men who, comprehending Him, have aided His own course of historical re-creation of the original ideal for mankind. Hence, the Unification view regards historical cycles as a "Providence of Restoration" restoring the original ideal and possibility lost through man's misuse and misunderstanding of himself and God.

It is useful, especially since the implications of ideology are most graphically expressed at the levels of personal experience and application, to review the very general results of atheism and religion as they apply to human life. These can be summarized in a number of points which plainly express the differences between dialectical materialism and a comprehensive religious view as it would be lived out by man.

1. Dialectical materialism contends that material is the source of all things. The Unification view looks to God as the ultimate first cause. There is a spiritual and physical complement to existence, an invisible world of God and spiritual reality outside space and time, and a physical creation complementing it as its finite image. Spirit and matter exist in mutual complementary and simultaneous oneness through give and take action.

2. According to communism there is no life after death because spirit cannot exist independently from matter. The Unification view acknowledges life after death. Man's life continues in the spiritual world through eternity, since this is the nature of that dimension. Spiritual and physical life are interconnected by the give and take action of their respective positions of subject and object, but the former remains forever.

3. Dialectical materialism focuses on social classes which struggle in antagonism through successive stages of domination and submission. The Unification view accepts that such conflicts and class antagonisms exist but does not assert that they reflect fundamental life processes. Rather they reflect a state that is "fallen" away from an original ideal that is as yet unfulfilled. The Marxist confuses the "fallen" state (tension and struggle in society) with the real and ideal principle of God in which lite is an expression of the oneness of love and the ideal of organic unity. Marxists, who assert in their metaphysics that contradiction is essential to life itself, have never achieved harmony and unity within their party, society, or nation.

4. Communism contends that history requires it to force its ideology upon others, as part of the universal pattern of struggle. Therefore, it does not regard human rights as primary. The Unification view, being a religious view, gives ultimate universal value to the uniqueness of personhood. Progress comes through service and love, not through dominance and force.

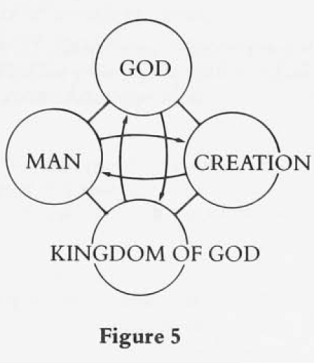

5. For the materialist, the ideal for man will be the communist Utopian state where man is properly conditioned to his nature. For religion, since the ideal is mutual harmony and unity of diversity, the future of man is very different. The contradiction of sin will be eradicated and man, a liberated spiritual and physical being united with God's spirit, will achieve the completed image of God: the Kingdom of Heaven on earth and in the spiritual world. (Figure 5).

There is one final aspect of the counterproposal to Marxism. It is the substantial counterproposal in the ministry of service and love. Sun Myung Moon has said:

Go to the most miserable place and volunteer. For whom were you born? For yourself, or for the sake of others? For the world, for God? God actually made us not to serve our own purpose but to serve others...

Why should an eye be made the way it is? An eye is made to perceive for the sake of the body. Your senses are all made to perceive others and to relate to others

The definition of a "saint" is very simple from this point of view. A saint is the one who sees not for himself but for the sake of the world, for the sake of God. His point of reference is not himself and he finds no joy in selfish living.

History has seen many great religions and great teachings, but all those doctrines put together point to one simple truth.

If our members must sacrifice themselves to save the people then the first one to suffer is me. People of the world are dying and desperately suffering. If they are your brothers and sisters, then you have to reach them and cry out for them.

At one time America was trying to serve the world. America is in a position to lead. If America's 220 million people were united together to give themselves for the sake of the world, how great America would be. Americans need to do just that.

You and I are here to tackle the major headaches of God. The will of God is the liberation of the world. We are gathered to participate in the historic mission in which Jesus and God will take delight. We certainly have the answer to communism.36

The substantial answer to communism is the substantial living out of religion or religious ideology in the ministry of works. In the Unification ideology, words and action form a polarity. One is in the position of Sung Sang, the other Hyung Sang. One has to do with the "Foundation of Faith" in God, the other with the "Foundation of Substance," the substantiation of these words and faith in life and action. Neither has any meaning without being bound together and united through give and take action centered on purpose. Thus, the Hyung Sang, or substantiation of the counterproposal to Marxism is the substantial ministry of serving works.

It is the task of religion to initiate a return of its devotees to this path of service, but not simply one with small goals. The movement must be massive, a complete challenge to those who believe to live their faith in a way that will lead to the real physical salvation of the world. God has had infinite capacity to sustain His sacrifice for others. In like manner, when God chose Jacob to lead a path of restoration and reconciliation to his brother Esau, Jacob left his usual ways, and under the persecution of scorn and accusation labored many years in Haran. Then, after he had amassed wealth of which others might be envious, he gave it all away. Christianity, and the richly blessed economic powers of the world are in this role of Jacob. The time has come for this kind of revolution within Christianity. Networks of groups and organizations must be formed to mobilize the churches to actual service. This has been the historical task left unfinished by religion. This has been the point of accusation and victory for the Marxist materialists.

Communism has succeeded where it has put its ideology into practice. It has not and cannot succeed ultimately because of its ideological weaknesses, but it has tried to impress the world with its willingness to work and sacrifice for its concrete goals. Christianity, though marked for its saints and its outbursts of sacrificial ideal, has had neither a universal ideology nor a unified and organized channel through which to serve. It has not been able to meet the requirements of its faith.

When Mao Tse-tung sent his troops into the villages of China, he said:

They (meaning the Nationalists) only come to collect the taxes. Go meet the village leader. Give the people your food, teach the people how to read.37