![]()

Proceedings of the Virgin Islands' Seminar on Unification Theology -- Darrol Bryant, General Editor - April 1, 1980

|

|

Proceedings of the Virgin Islands' Seminar on Unification Theology -- Darrol Bryant, General Editor - April 1, 1980 |

The history of mankind, from Adam and Eve until now, is really the result of the fall of man. In other words, if Adam and Eve had fulfilled their responsibility and perfected themselves in God's image, they would have established the kingdom of heaven on earth from the very beginning. Because of the fall, history took a different course; but even so, God continues working to establish his original ideal of restoring the world to its original state of sinlessness. Therefore, we refer to history since the fall of man as the history of restoration.

It could also be called the history of re-creation. God is re-creating mankind according to his original plan. Just as there were certain principles governing the original process of creation, so there are also principles governing the process of re-creation. A most fundamental and important principle here is the principle of re-creation through indemnity which takes place as mankind indemnifies or makes restitution for sin and evil. Before we pursue that in detail though, I want to go through general patterns of restoration that also apply to every person.

Adam and Eve should have originally gone through the three stages of growth to perfection. However, when they fell, they dropped even lower spiritually than the formation stage. They formed a four-position foundation centered on Satan which led to the involvement of Satan in human affairs. Therefore, the first important point in the process of restoration is that we have to separate from Satan. We must learn how to disassociate ourselves from him, from his viewpoint and his ways. That is the very beginning of the course of restoration. Then man needs to grow spiritually until he stands at the top of the growth stage. At that point, there is a foundation for the messiah to come. Then man must receive the messiah and be reborn through him, after which man is freed from original sin and can continue growing to perfection. The messiah is the one who has already perfected himself by going through his own course; by following him, we can attain our perfection, and having done that we can fulfill the purpose of creation by establishing a perfect family and an ideal world.

Now, I would like to speak more specifically about the principle of indemnity. Fallen man stands in the position between God and Satan. We have the original nature that God instilled in us. It still exists within every person and as a result, there is a basis for God to relate to fallen man. However, each person also has fallen nature, so there is also a basis for Satan to relate to man and lead man in his direction. Thus, fallen man is in a midway position between two masters. Therefore, neither God nor Satan can have complete dominion over fallen man. The degree to which God or Satan will have dominion over a man is determined by that man's own actions. If he acts in accordance with God's will, then he creates a foundation for God to act in his life; however, if he commits evil acts, then there is a basis for Satan to have dominion.

Now, once something has lost its original status, in order for it to be restored to that original status, effort must be exerted. If some wrong has been done, restitution must be made. Sins must be "indemnified, " but there are different degrees of indemnity. We might speak of indemnity of an equal amount if the amount of restitution to be made is equivalent to what has been lost. The Old Testament calls this an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. However, there might be a situation in which the indemnity to be paid is actually less than the loss. Although it is a partial payment, it is accepted as payment in full. Thus Jesus himself took the way of the cross in order to make restitution for man's sins, but we don't literally have to be crucified. We can be resurrected by virtue of our belief in him, and the indemnity that we thereby pay is much less than the indemnity Jesus paid. There might also be a situation in which greater indemnity is required. If a certain amount of indemnity is required at one point but is not paid, then a greater amount of indemnity might be required later. For example, if a central figure in God's providence fails, then the next one to come along must pay the indemnity not only for his own situation, but also for the failure of his predecessor. When failures occur in providential history, then the amount of indemnity to be paid increases, and the situation becomes very complex. So indemnity can be of equal amount, lesser amount, or greater amount.

Who is responsible to pay indemnity? It was man who failed to fulfill his portion of responsibility, not God. Man can be restored to his original position and freed from the dominion of Satan only if he fulfills his portion of responsibility. However, because of original sin, man is not really able to free himself from the dominion of Satan. That takes place only when the messiah comes. Man is freed from the dominion of Satan by being reborn and cleansed of original sin through the messiah. Fallen man can only provide conditions; he conditionally or symbolically affirms his desire to relate to God and separate from Satan. He partially or conditionally fulfills the original portion of responsibility, which is obedience to God's word and commandment.

How is an indemnity condition made; what will indemnify something? Indemnity is paid by reversing the course of the fall. In other words, it is simply the reversal of the process of deviation from the original status. In order for us to be restored to the position which Adam and Eve lost, according to this principle we need to indemnify their failure. However they failed, we are going to have to reverse that process. The question then is: What did they fail to do? First, Adam was supposed to establish what we call the foundation of faith, by obeying God's commandment. The foundation of faith is a vertical relationship between God and man, established through living in accordance with God's word. However, as we know, Adam and Eve turned away from God's word and fell, thus failing to establish this vertical relationship and this foundation of faith.

Man also failed by establishing a fallen relationship with the archangel. Man failed to keep his original position in the whole scheme of things, the position of child of God and true lord of creation. Man actually put himself under the archangel's direction, rather than standing in a position to give direction to the archangel and guide him in accordance with God's will. Now, man's original and proper relationship with the creation, including the angels, is what we would call the foundation of substance.

Thus, in disobeying God's commandment, man failed to establish a foundation of faith; and in submitting to the archangel, man failed to establish a foundation of substance. Therefore, some central person in God's work of restoration must stand in the place of Adam who failed, and must lay the foundations of faith and substance which Adam failed to establish. Since Adam and Eve were to have grown to perfection through a period of time, the process of restoration also involves a certain period of time. So we have the following elements in the foundation of faith: some central person representing Adam, some condition that must be met, and a certain period of time during which this must be fulfilled. And since Adam and Eve were supposed to establish a God-centered dominion over the creation, including the angels, the process of restoration also requires a condition of indemnity to remove fallen nature by correcting the improper relationship between man and the archangel. So we have the following elements in the foundation of substance: a central person to represent Adam and someone to represent the archangel.

When fallen man establishes the foundation of faith and the foundation of substance, the foundation for the messiah is set. The foundation for the messiah is this combined foundation.

Now, each of us is actually a historical being. We are products of what took place in the past and we are also looking forward to the future. What has affected those in the past affects our lives now, and will affect the lives of our descendants in the future. If people in the past have been able to contribute to the success of God's providence according to their ability to understand what God is really trying to accomplish, then it is important for us to understand how God has been working throughout human history. Making use of the general principles I have just described, we can begin by looking at the historical accounts that we find in the Bible, starting with Adam's family.

God initially gave Adam two sons, Cain and Abel. Through these two sons, God wanted to separate good and evil symbolically. I say symbolically, because actually both Cain and Abel had an original nature of goodness and a fallen nature of evil. Nonetheless, as we shall see, it served God's providence to have one son represent evil and the other, goodness. The question is: Which would represent good and which, evil? That was determined by the actual process of the fall itself. Two relationships take place in the fall: the relationship between the archangel and Eve and the relationship between Eve and Adam. Through these relationships, mankind fell. In the first case, the relationship between the archangel and Eve, the motive was entirely self-centered, entirely against God's will, and thus extremely evil. The relationship between Adam and Eve was also an evil relationship. Nonetheless, there were mixed motives on the part of Eve: her fallen mind was moved in accordance with Satan's wishes, but her original mind longed to return to God. She was attracted to Adam partly because he was, before he fell, closer to God; and in this respect, her motivation was partly God-centered. Furthermore, even though the relationship between Eve and Adam was premature and against God's will, none the less the relationship was ultimately supposed to take place, unlike the relationship between Eve and Satan, which should never have occurred. So from God's perspective, there was some basis to look at this second relationship as less evil, or in a sense more forgivable. Thus, the first son, Cain, represented the position of evil, that is the first relationship. Of course, both Cain and Abel were the offspring of the relationship between Eve and Adam and not Eve and the archangel. Nonetheless, Cain was in the position to represent the first fallen relationship, while Abel was in the position to represent the second one. Thus, Abel represented Adam, and Cain represented the archangel.

According to Genesis, both brothers made offerings to God, but God found Abel's offering satisfactory, and he did not favor Cain's offering. And Cain's countenance fell and he became angry, and then God said to him, "Why are you angry, and why has your countenance fallen? If you do well, will you not be accepted? And if you do not do well, sin is couching at the door; its desire is for you, but you must master it." (Gen. 4:6-7) Cain was upset. But Abel made his offering in a way that was acceptable to God and thereby fulfilled the foundation of faith. The next step should have been the foundation of substance, which could have been fulfilled if Cain had then humbled himself to his younger brother. The original relationship between Adam and the archangel should have been such that Lucifer loved Adam just as God loved Adam. He would then have received God's love and direction through Adam. But the relationship was never realized; instead, Satan came to hold the subject position, and wanted Adam to love him and follow his direction. Now, in order to indemnify that fallen relationship, the relationship must be reversed. Cain had to love Abel just as God loved him, and he had to receive God's love and direction through Abel. In order to have his offering accepted by God, Cain needed to make his offering through Abel, and relate to God through Abel. Instead, as we read in Genesis, Cain killed Abel, and the foundation of substance was never established. Consequently, the foundation to receive the messiah was never established, either.

A fundamental lesson to be learned from this is that the person in the Cain position must come to God through the person in the Abel position. Fallen man is able to come closer to God by following a good central figure, a person through whom God is working. Cain had to come to God through Abel, and that is true for fallen man in general. Finally, the messiah comes in the position of Adam, the ultimate Abel, and all of mankind stands in the position of Cain, and comes to God through the messiah.

Participant: By the time you have gone through the position of Lucifer, Satan, Cain-lineage, Abel-lineage, even though you say positive and negative are to be understood in terms of electrical charges and not in terms of moral or valuative terms, I can't escape the impression that now we are somehow working with a moral evaluation. Are Cain and Abel involved in the give-and-take action, the polarity idea too?

Joe Tully: Of course they are. But in their relationship, as with all human beings, there are some original and some fallen aspects. Simply because there is a give-and-take relationship doesn't mean that we are speaking only about men and women. We talk of give and take between men or women.

Tom McGowan: I would like you to clarify the question of indemnity because I am having real trouble with that. This morning when I raised the question of indemnity one of the Unification respondents said that I had missed the point, that it doesn't mean paying back. Now you defined indemnity at one point as the "reversal of a process of deviation." Let's leave aside the fact that you are playing with language here, taking a word that means one thing in an English dictionary and transposing it to a theological context. This can be confusing, but we are all at times guilty of it. But you also used the words paying indemnity. So there is this concept of payment, and it does begin to sound exactly like paying back. If so, there is a question of to whom is paid. Now that is a good question because there is one strong tradition that says God is paid and another equally strong tradition that we pay Satan. I would like to hear Unification theology on this point.

Participant: Also, you can move from various levels of understanding but I wonder if you could become very concrete and tell me, Joe Tully, whose bad karma are you indemnifying? How are you doing it in your life?

Joe Tully: A very interesting question. To a large degree it's my own sins, but we also believe our lineage's sins affect us.

Participant: You are working out something from your immediate family and your ancestors?

Joe Tully: I think that is to a large degree evident; we can't help but be affected by our families. My parents teach me, and the kind of ideas they give me are things I have got to work out.

Herbert Richardson: The word "indemnity" creates problems, and the biblical word that we all know and that we might think about here is the word "sacrifice." In the Old Testament there is a highly developed practice of sacrifice. What sacrifice does in the Old Testament is maintain the ecological balance of both the natural and the moral order. There is such a thing as the ecological balance of the moral order: the words "eye for eye and tooth for tooth" are saying that evil has to be balanced out in some way, and that is through, in part, the practice of sacrifice.

Now just a couple of observations. First, in the Old Testament there are guilt sacrifices and there are thank offerings; sometimes you offer a sacrifice to make amends for an evil deed that has been done, and sometimes you offer a sacrifice to add your blessing to a blessing you have received. Here is what you have in Unification -- not because anything has happened to you but because you want to start something happening. This is clearly not the "payback" type of thing. The whole practice of sacrifice is related to the order of the moral universe which is understood to operate under the rule of justice and harmony. If Unification theology is to take seriously many of the fundamental ideas of the Old Testament, one of which is the idea of sacrifice in the many modalities in which sacrifice appears, then problems arise. I can think of two of them. The first is that the word "indemnity" does not capture in our ears the idea of a moral universe maintained by justice and a certain harmony to which the person has to orient himself with the attitude of sacrifice. The way you are using the word indemnity does not plug us into the Bible. And the other problem is that in the entire Christian tradition there has been a movement away from the idea of sacrifice because we say that Jesus paid the full and final payment, and thereby abolished the cult of sacrifice. The belief that the universe, the moral universe, is governed by an order of justice to which we have to relate through the practice of sacrifice is undercut, even though in the Catholic tradition the notion is preserved by the idea of repeating the death of Christ as a sacrifice for maintaining the harmony of the moral universe. Protestants have given it up completely and moralize the idea of sacrifice as if it were penance for getting rid of guilt. I feel that this is the root of the problem of understanding that we are having. We have so forgotten the meaning of sacrifice in the Old Testament sense of the word that we can't understand what you are saying in any sense except that sense of guilt and payment back. That is characteristic of the modern rationalistic mentality. Something has to be done, therefore, to resurrect the whole biblical context of the idea if we are to understand what you are saying.

Joe Tully: Let me make a couple of points. First of all, indemnity is not intended to engender a feeling of guilt. If I am aware that I have damaged a relationship, I think the proper way to approach it is to show that person that I would like to put things back in their original order.

Herbert Richardson: Excuse me, but that is why I think we misunderstand you. We don't have either the Oriental sense of the moral universe or the biblical....

Joe Tully: You think the word "sacrifice" says it all?

Herbert Richardson: I think that you haven't invested your explanation with sufficient meaning for us to understand. I personally believe your doctrine is true, because it is simply a spelling out of a whole understanding of sacrifice as a method of relating to the moral order as articulated in the Bible. But you must be clearer in your explanation.

According to the principle of creation, we grow spiritually by living in accordance with the word and the principles of God, thereby fulfilling our portion of responsibility. However, the nature of fallen man is fundamentally different from that of original man because of original sin and fallen nature. Therefore, fallen man is incapable of really fulfilling his original responsibility; so God gives fallen man certain conditions, through the fulfillment of which man can be considered to have symbolically fulfilled his portion of responsibility. Now, in the process of reaching the original state of perfection we go through two fundamental phases: the way of restoration and the way of principle. The way of restoration brings us back to the top of the growth stage from which our ancestors fell; and then at that point we receive the messiah, and through our relationship with the messiah we are reborn and freed of original sin. From that point on, we must grow to perfection by fulfilling our original portion of responsibility. This final course through the perfection stage is the way of principle, the second of the two major phases.

In the process of restoration, indemnity conditions are very important. Without them, we would never be able to reach the way of principle, since our fallen nature prevents us from really fulfilling our portion of responsibility. So indemnity is not simply a burden of hardship, but a way of compensating for our diminished capacities. Furthermore, indemnity is more than a sacrifice or an offering. Not only is there a time period involved, but also internal qualities of attitude and heart. Mere fulfillment of external requirements is not enough: man must make his relationship with God the center of his life. Then the proper horizontal order between man and the creation, including the angels, has to be re-established. This is the foundation of substance. When these are established, the messiah can come.

So the goal of history has been to prepare the foundation for the messiah, first at the family level, then the national level, and finally the worldwide level. Starting with Adam's family, God sought to have Abel accomplish what Adam failed to do. Abel made an offering in compliance with God's will and thus established a foundation of faith; but because Cain killed Abel, the horizontal relationship between Adam and the archangel was not restored, and the foundation of substance was not established. So Seth replaced Abel and out of Seth's lineage came Noah. By building the ark in accordance with God's instructions. Noah re-established the foundation of faith. The horizontal order was to have been restored by Ham, who should have inherited his father's position, and by his brother Shem. We can't go into the details of the story at this point, but Ham failed to inherit his father's position, so the foundation of substance could not be established. After Noah came Abraham. Abraham re-established the foundation of faith by offering to sacrifice his son, Isaac. Then Isaac's two sons, Jacob and Esau, came in the position of Abel and Cain to establish the foundation of substance. And for the first time in history, that was accomplished when Esau welcomed Jacob upon his return from exile. Finally, God had a family foundation for the messiah.

The providence then moves to establish a national foundation for the messiah. God named Jacob "Israel" on account of his faith, and his family expanded into the nation of the Israelites. After this expansion took place, in Egypt, Moses re-established the foundation of faith to become God's new central figure. So Moses was in the position of Abel, and the people of Israel in the position of Cain. The people were supposed to respond to him in obedience, receiving God's direction through him; but the Bible tells us that they failed repeatedly. Because of their failure, the providence was further delayed -- as it always is when man fails to fulfill his portion of responsibility. But finally, by its obedience, the nation of Israel was able to establish a national foundation for the messiah. Yet in spite of all this preparation, when Jesus came he was not received, but rejected. Because of this rejection, another foundation for the messiah has had to be established, this time on the worldwide level. That, in fact, is the purpose of Christianity. Just as the Israelites were supposed to establish a national foundation for the messiah, so Christianity is supposed to establish a worldwide foundation for the messiah.

Because of man's repeated failures, history shows a certain cyclical nature; certain kinds of events repeat themselves in the effort to establish a foundation for the messiah. When there is a providential failure, God has to find another person in another era, and repeat the attempt. Thus, we see a parallel relationship between the history of the Israelites and the history of the Christians. In fact, we see six major sub periods that are parallel to one another. Briefly we see in Israelite history roughly four hundred years of suffering and oppression in Egypt, followed by four hundred years under the judges, then a one hundred and twenty year period of the united kingdom, four hundred years of the divided kingdom, a two hundred and ten year period of exile and return, and then four hundred years of preparation for the messiah.

In Christian history, we see, again roughly, four hundred years of persecution, followed by a four hundred year period under the Church Patriarchs, then a one hundred and twenty year period of Christian monarchy, four hundred years of divided kingdom, a two hundred and ten year period of papal exile and return, and then, starting with the reformation, four hundred years of preparation for the messiah.

The main reason for the delays in God's providence (and thus for these historical parallels) has been man's failures. Actually, the foundation for the messiah could have been established many times if only man had adequately responded to God. Despite our many failures, God continues trying to inspire us to fulfill our responsibility; that is, to establish the foundation of faith and the foundation of substance. These are the basic elements of the Unification view of providential history.

Darrol Bryant: As everyone is aware, there were a number of questions and issues that were raised yesterday afternoon and this morning that were not exhausted. We thought we could pursue some of them in this half hour. Mr. Tully has laid out some of the structure of Unification belief on the relationship between providence and history. Yesterday there was some discussion of the principles of resurrection. Some of you were in the same position as I: having some difficulty understanding what the question was to which this material in the Divine Principle was being addressed. Perhaps in this discussion we can get some clarification. What exactly is being addressed in this part of the Divine Principle?

David Paulsen: I want to talk about indemnity and restoration. I think that Christians today have to recognize that a real part of Christian life involves letting God undo the damage that has already been done in our life by sin. This is what Christians have usually called sanctification and growth in faith. What I found almost totally missing is the idea of justification by faith that emerges very clearly in Romans and Galatians. I have heard almost nothing about that that is crucial. I really have trouble with the statement in the Divine Principle on page 174 which says that God carried out the providence of resurrection in the formation stage in such a way that people were justified by believing in and practicing the law of the Old Testament. Now in Romans and Galatians it says just the opposite. It says very clearly that Abraham was justified by believing. Abraham believed God and God counted it to him for righteousness; that theme runs throughout Romans 3 and Romans 4 and Galatians 2 and 3. You have statements, for example, in Galatians 3, that those who are men of faith are blessed with Abraham who had faith. But in the Divine Principle it says that Abraham failed to have complete faith. It is very clearly stated in Romans and Galatians that he was the father of faith and that the men of faith -- Christians who believe in Christ -- are blessed with Abraham who had faith. I would like to see how you resolve these differences.

Durwood Foster: I think that last suggestion is really very interesting and plausible in a broad way. I wanted to make some brief observations about the parallels between this part of the Divine Principle and what has gone on in the history of Christian thought and reflection. At first glance, it might seem that these sections of the Divine Principle are rather bizarre compared to the way we, for the most part, do theology today. Nevertheless, historically, it seems to me there are some striking parallels. What first comes to mind is the whole development of covenant theology and the very elaborate way in which the various covenants -- in one fairly standard version the five successive covenants -- were worked out in the federal theology according to different historical dispensations. Very much of the same material was used. There was the Adamic covenant, or the primordial covenant, then the Abrahamic covenant and the covenant with Noah and all of these were covenants of works. Eventually they were superseded by the definitive covenant of grace and the whole movement was resolved. I don't want to dwell on this in detail, I just want to observe that a similar thematization did go on in historic Christianity.

Another somewhat parallel development that exists in the history of Christian thought is the very elaborate way in which in scholastic thought (and thenceforth down into the modern Catholic tradition, though rather dropping out of the picture since Vatican II) the reciprocal interrelationships between the order of grace and the order of merit were worked out so that a very careful interplay between what God undertook to do and then left to human beings as the human portion of responsibility was articulated and elaborated. An interesting recent review and discussion of this whole development is found in Karl Barth's Church Dogmatics, vol. 4, part 2. Of course, Barth is very sharply critical of it since, generally speaking, it is true that in Protestantism the whole theme of reciprocal synergistic interplay tended to be abolished. But nevertheless in any kind of ecumenical Christian discussion today, I think that these questions would have to be reopened.

My point is simply that there are these general parallels between what the Divine Principle is undertaking at this point and what has historically been part of Christian thematization. Now I wanted also to suggest that in some general way what is being told us this morning is prima facia acceptable in terms of a common Christian understanding of historical providence and dispensation. That is to say that in some broad way, Judaism is a period of preparation for the coming of Jesus Christ as the center of history. Then, following upon that, the period of Christian history is a period of further preparation for the consummation of history, or, if you will, for the second coming. It seems to me there is nothing novel or heretical about this at all, though finally it will depend on how the second coming is construed. But in terms of the broad picture, this is very normal and orthodox. In Christian history there would be various ways in which this might be worked out. I was thinking at one point, for example, of the view of Franz Rozenzweig who construed Christianity as a kind of diaspora of what had been a nucleus -- an intensified core -- prepared in Judaism. But in Judaism the preparation had not, we might say, laid a worldwide foundation. So, in order for what had been prepared in Judaism to be given as it were a worldwide foundation -- or dispersion, in Franz Rozenzweig's view -- Christianity comes into the providential picture. It seems to me that this is very parallel in some basic aspects to the Divine Principle. That is to say, what went on in the history of Judaism brings things up to a certain point, but it is not universalized enough. Hence, it has to be carried on in a way that does truly universalize it. It is the vocation of Christianity to carry on that universalization, and when it is completed we are at the point at which the consummation can then take place.

Darrol Bryant: Thank you, that was very helpful.

Joe Tully: I wanted to address, first of all, the question of faith. I meant to give the impression that the first aspect of man's responsibility, both in the original course and in this process of setting the foundation for the messiah, is fundamentally and essentially bound up with the question of faith. We have said that man had to be faithful to God's word, had to obey God's word. Establishing a foundation of faith in this first part of restoration is absolutely crucial. Without demonstrating proper faith, we can't even begin to move out of the condition in which we find ourselves. So though there is still discussion on the actual content of faith -- of whether it is God who does the total work as you were suggesting or whether there is a portion of responsibility for man -- I want to be clear about the importance of faith.

The very last verses of Matthew 28, when Jesus says to the disciples, "Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you" makes clear that faith is receiving and practicing the word of God. I think that is exactly what Jesus is commanding there: teach them to observe all that I have commanded, and not simply believe.

The question of whether it is God alone directing and inspiring faith or whether it is partly man's responsibility is, I think, a very serious question. But if God is entirely responsible for the faith that we have, then that means that when we have insufficient faith, it is because God has not given us sufficient faith. That's one problem if you don't have some notion of man's portion of responsibility.

Lloyd Eby: Let me say a few more things about this question of faith and Abraham's justification by faith as it is explained in Romans and Galatians. I think that one of the things that is at stake here is the question of what faith means. It seems to me that in the Protestant tradition, especially the Lutheran tradition, faith has been interpreted almost completely mentalistically; at least it has primarily meant something that one does as an internal spiritual thing. Now I think that in the Divine Principle the claim is being made that yes, indeed, Abraham was justified by faith, but that that faith is simultaneously the having and the maintaining of an attitude and a showing of that attitude by means of some kind of outward expression. The claim that is made in the Divine Principle about Abraham's failure in faith is that that outward expression failed and therefore it had to be repeated in a second attempt. The Divine Principle claims that Abraham failed in the first offering of separating the offering -- the sacrifice of the animals -- and therefore had to offer his son Isaac. Now notice that in the talk about the foundation of faith and foundation of substance in the Divine Principle the claim is that it is faith that needs to be restored as the first condition of accomplishing God's providence. But the restoration of faith is shown through some external manifestation so that the having of the attitude without the external manifestation accomplishes nothing. It is the external manifestation which, so to speak, consummates the faith. The Divine Principle is not denying grace but it is saying that the method of appropriation of grace is through man's fulfilling his part in the divine economy, and that the divine economy is a cooperative project between God and man. Man's part in this is to have faith and to manifest that faith by consummating it in some manifestation of it. So grace cannot be given to man; God's grace is there all the time, but in order for man to appropriate that grace, man has to fulfill his part in this economy.

It comes back to the meaning of the term "indemnity." I am not happy with that term, but the problem is that any other term I can think of doesn't really solve the problem either. If you notice in the green theological affirmation booklet1, the term "reparations" is used. I am not sure that that is a much more helpful term. Sometimes I use a colloquial expression: "you got to pay your dues." In the original principle of creation, responsibility for the accomplishment of God's providence or God's ideal is given to man. And what the principle of indemnity is basically saying is that this responsibility in some fashion or other remains with man even after the fall. Of course God's grace is given to save man, but something must be done on the part of man to respond to that grace; then that grace can be appropriated. This response is indemnity. I think a lot more needs to be said about that, but let me move on.

The Divine Principle, as I understand it, is claiming that the vertical relationship with God is the foundation for success in the horizontal relationship. Or, to put it differently, both relationships are absolutely essential, but the vertical one takes precedence, or needs to be established before the horizontal relationship. I hope this helps to make things clear.

Charles Norton: What I really wonder about is whether or not, from God's perspective if you got one family perfect, might not that be "premature sub optimization"? You would have perfection in too small a spot.

Lloyd Eby: I don't think so. My understanding of the Divine Principle is that in God's providence this optimization is an unfolding process so that subsequent developments depend on the completion of any prior developments. If that is the case, you have to have complete optimization in a small unit before that can be expanded to a larger one.

Charles Norton: What I am saying is simply a different way of looking at it. That is, the way it is represented in the Divine Principle, it looks like a little progress and then a failure, and then for some reason progress seems to be going on through the next period and then the next failure. All I am saying is that you could change your perspective and say that that wasn't a failure at all. God was just stopping before he got sub optimization, and he kept on moving right on.

Darrol Bryant: There are several comments or questions. We'll go in the order I spotted you.

Frank Flinn: As a Roman Catholic I am perfectly happy with the word "indemnification." So I would like to address this to my Lutheran colleague. There is a curious aspect of evangelical theology that I have trouble with, and that is that I think Paul's notion of justification gets elevated out of context. Why is it that Paul uses the word "justification" only a couple of times in all the Corinthian literature, whereas we see an explosion of justification language in Galatians and Romans? That is not explained to me by the evangelical tradition. What is going on there? Why should we absolutize justification? Can we absolutize agape? I am a conservative Catholic and I don't think we can absolutize either one. We have to find the proper context for each one as well as for the notion of indemnification. From a metatheological level, what I see going on with the whole notion of indemnification is something like this: Catholics from the medieval tradition make a distinction between different kinds of merit. The first one we call meritum de condigno. I call it merit that is merited. And the second is called meritum de congruo; that is, merit that really isn't merited but God finds it fitting to let it be merited. Now what I see going on with the theological concept of indemnification is a mediation of that Catholic notion of meritum de condigno with the Protestant notion of justification. Hence by comparing indemnification with justification we are going to fail to see the point. What Unification theology is doing with the notion of indemnification begins, I believe, to resolve a classic conflict between Catholics and Protestants, and opens up a whole new field for theological reflection.

Responding to Charles -- and I agree with you -- it is actually in the Divine Principle that, for example, communism is a false anticipation, a sub optimization. But the problem is that the Unificationists don't have an adequate theology of evil.

Jonathan Wells: We have now heard from the Lutherans and the Catholics. I've been waiting for the Calvinists and Wesleyans to point out that we have heard very little about sanctification in this lecture. Because of the way the Divine Principle is taught, it often seems that we are saying that by a gradual process of works righteousness we achieve justification. But that seems to me to be a misunderstanding. According to the Divine Principle, even under Satan's dominion we have an original mind. God's grace reaches our original mind and inspires us to approach him, and that is justification. Now the process of indemnification is a process of sanctification: that is, a gradual process of purifying ourselves so that we can relate more closely to God. The end that we are talking about is not justification, but restoration, which in its final stage is complete union with God. First comes justification, then sanctification, and finally restoration.

Bettina Gray: I would like to address myself to the question of the picture of eternal life because this has always been part of the Christian question. As you explain it, structures of horizontal and vertical have more to do with the kingdom of heaven on earth now, or within three generations. And the personal practice of identifying with God is spoken about in terms of family life. But a great part of the Christian tradition has understood "be perfect even as I am perfect" as an eternal commandment requiring a continual perfection. Others say that if you are saved by Jesus, you instantly have eternal life. I would like to hear some comment about the perspective of eternal life within this structure.

Kapp Johnson: This is partly a question and partly a statement. I think that part of the problem that we are all having in trying to grasp the concept of indemnity is really one that is a problem in classical Protestantism, namely, the problem of God's complete power and responsibility. That is not just a Unification problem. Now what seems to be evident to me in the Divine Principle is that there is an aspect of limitation of God's power. On page 283 of the Divine Principle it says that the providence of restoration cannot be fulfilled without man's joint action with God. On page 341 it says that even God cannot grant man grace unconditionally because Satan came to possess man under the condition of the fall and could accuse God of unfairness if grace were given unconditionally. However, the situation of the covenant in the Old Testament is not that of two equal people coming together to mutually support one another, as in an alloy where you bring two weaker metals together to make a stronger metal. That is not the purpose of the covenant in the Old Testament. God does not have a covenant with Israel in order to make himself stronger and to make his power more effective. So I see a fundamental problem in the Divine Principle as one of understanding the Old Testament covenant.

William Bergman: To the question of God's power alone. The viewpoint of the Divine Principle is that God cannot accomplish his will without man responding freely and fulfilling his own portion of responsibility. I think this is validated in the Old Testament: for example, in II Chronicles 7:14 God said if my people who are called by my name humble themselves, and pray and seek my face, and turn from their wicked ways, then I will hear from heaven, and will forgive their sin and heal their land. Clearly God's capacity to hear, to heal and to forgive is contingent on man fulfilling certain conditions of turning towards God.

Myrtle Langley: I wish to ask how, from the Unification point of view, rebirth takes place?

Anthony Guerra: I wanted to amplify one point that Dr. Bergman was making about God's power. Fundamentally we want to emphasize God's love, and would say that it is precisely because of God's love that he limits his power. The goal of restoration is not God being alone and somehow satisfied. It is the fulfillment of the purpose of creation. God's nature necessitates a response. I think that is fundamental. In other words, the idea of irresistible grace is rejected, as I think it is rejected by most theologians today. But we have heard that idea in this discussion. We would reject the idea of irresistible grace and would say that there is some response necessary -- as in the idea of a covenant. Even with the covenant you still have the possibility of either breaking the covenant or not breaking the covenant; that is the form of the human response in the Old Testament.

I just wanted to make one other point about the question of eternal life. In Unification theology we believe that the eschatological state is not simply a state in which the individual comes to a full relationship with God. Rather we maintain the Christian notion of a community of saints, with the stress on community. To spell that out more specifically, we believe there will be eternal families and marriage relationships. Salvation takes place within a community in a world of people who live together not simply as individuals connected to God but also related to one another. This is the whole point of the history of restoration. The principles that we have been talking about are a foundation of faith and a foundation of substance, a foundation of faith in which individuals become reconnected to God and a foundation of substance in which God's family is reconstituted. Brothers are brought together, clans are brought together, nations are brought together. Ultimately the world is brought together. This history is not circular but it is definitely cyclical. It has a linear direction also. It is history in preparation for the messiah. In both the Old Testament and the New Testament, history is given a linear direction that is not simply a repetition or simply circular as in the Greek view of history.

Finally, I wanted to make one final comment on the question that was raised concerning the purpose of the resurrection lecture. It has something to do with the notion of spiritual life. In a sense the lecture on resurrection seeks to explain spiritual phenomena. Theologically, it addresses itself to the question of what you do with all the people who live in the spiritual world before Jesus comes. Darrol Bryant: It is that time. But I acknowledged Mr. Salonen and I want to give him a chance to comment.

Neil Salonen: One point I want to make is that there is a distinction in our thinking between eternal existence and eternal life. What we are actually saying is that from the moment of your creation, your spirit exists eternally. This does not depend on whether you want to or not; whatever you do, your spirit continues to exist eternally. But we define eternal life in terms of our relationship to God; so although you have an eternal spiritual existence, in order to attain life you have to develop your relationship with God. That is really an important point. The whole purpose of the resurrection lecture is to explain what happens to a person's spiritual being before they reach a certain relationship with God, or a certain understanding of the gospel, or enter into a faith relationship with Jesus.

I want to make one other point about rebirth. There is spiritual rebirth and there is also complete restoration. We enter into a relationship with God for the first time through our rebirth through Jesus and the Holy Spirit. However, we also look to the time when that relationship can be substantiated in the physical world. We believe that can take place at the time of the marriage blessing; marriage is the point at which we reestablish our relationship with God, at least conditionally, in the physical sense.

In a recent article in Evangelische Kommentar, Rolf Rendtorff, the Old Testament scholar at Heidelberg University, reviewed a book by Carl Amery who makes the charge that Christianity is fully responsible for our present secularized view of the world as well as for the exploitation and devastation of the created order2 Amery's thesis is worthy of a separate discussion. What I would like to do here is underline some of Rendtorff's observations on the relation between creation and history as they relate to our theme, providence and history in Unification theology.

Rendtorff notes how in the modern secular view of man's relation to nature, man is seeking -- to use the words of Francis Bacon -- empire and dominion over things themselves. The way we are doing this is by technological mastery. And behind the secularized belief in the end of history is the deeper belief that in gaining mastery over the physical world we will win back for ourselves the true image of God spoken of in Genesis 1. Rendtorff argues that Francis Bacon and Rene Descartes, in particular, and the modern technological society, in general, have gotten the biblical message backwards. The image of God, he stresses, is prior to and hence the precondition of exercising dominion over creation.

Rendtorff goes on bluntly to lay the blame or at least a significant part of the blame at the doorstep of modern liberal and, strangely enough, neo-orthodox biblical theology. One common feature of modern theology has been to stress history and the doctrine of redemption as an historical event at the expense of both the doctrines of creation and glorification. (Students of the early Church will recognize these three doctrines -- creation, redemption and glorification -- as the articles of the Christian creeds. Calvinists favor the term "glorification" for the last article, while Roman Catholics use "sanctification" and the Eastern Orthodox stress consummation and the theosis of man). Our modern preoccupation with history as redemption has led us into a distorted relation with the created order and has befogged our perception of time and space as the theatrum gloria: Dei.

In biblical theology we have someone like Gerhard von Rad, the great Old Testament scholar, who finds the heart of the biblical teaching in the so-called "historical credos" (Dt 6:20-24, 26:5-9; Josh 24:2-13). Von Rad calls Josh 24:2-13 "the 'Hexateuch' in nuce."3 If you examine the "historical credos" carefully you will find that there is an awful lot of talk about God acting in history but little or none about the meaning and purpose God established in creation. For von Rad, the starting point for biblical theology is history or Heilsgeschichte and not creation. However, it goes without saying that for the biblical authors, historical events like the Exodus were not a sufficient starting point.

If we turn our attention to the neo-orthodox theology of Karl Barth we find a parallel situation. Although Barth was reacting against the historical immanentism of the nineteenth century, he succumbed to it nonetheless in a peculiar way. In Dogmatics in Outline he declares unequivocally that the New Testament expression "Jesus Christ is Lord, " which pertains to the second article of the Creed, is the true first article and that the first and third articles are merely secondary elaborations. "Indeed, " writes Barth, "the second article does not just follow the first, nor does it just precede the third; but it is the fountain of light by which the other two are lit."4 In order to be fair to Barth, however, I must point out that he was rightly reacting against the naive optimism of liberal humanism. We must not forget that his monumental commentary on the Epistle to the Romans was written during the devastation of Europe in World War I.

Now I would like to make some remarks on the consequences of both the historicist liberal and the neo-orthodox positions. In both, the doctrine of creation, as Rendtorff states, is reduced to ein Mosses "Dass, " a contentless "That." In historical biblical theology, creation becomes a mere "prelude" to the "real, " i.e., to the historical. In Barthian theology, which underlines the wholly otherness of God and the radical fallenness of creation, we really cannot know very much about God's providence in the created order. Even the revelation of God in Jesus Christ is God's "No" to the old Adam. Because the theology of creation drew a blank in Barth's system, the secularist theologians came along and tried to fill it in. But they did this in a very Barthian way. For people like Friedrich Gogarten and Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the theological statement that "God is Creator of the earth" meant that the world was dedivinized and desacralized such that man was now free to assert his supremacy over the created world in history. As Gogarten put it, the world was now free to be "only world." What the secular theologians fail to do, however, is to make a distinction between domination, by which man claims a man-centered supremacy over the created order, and dominion, a shepherding of creation in a God-centered way. The secular theologians fall into the absurd position of making pollution seem "providential."

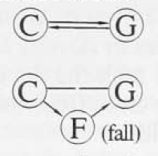

For a moment now I would like to make a digression and refer to the diagram I have made on the blackboard. (I just want to prove that Unificationists are not the only ones who can make diagrams!) What I try to represent here are two ideal types of theology. I understand "ideal types" in Max Weber's sense. You will probably not find a pure form of either one. Here is the schema: I would like to stress at the outset that I intend this theological schema as a heuristic device, not as a cookie-cutter.

First, the left side of the schema (C-R-G) represents the fullest possible Judeo-Christian theology. Hence the capital letters and the connecting lines. By the capitals and lines I want to signify fully articulated doctrines of creation, redemption and glorification which are interrelated. The other side represents the weakest possible Judeo-Christian theology. Hence the miniscules and the slashes (c/r/g). By the miniscules and the slashes I signify minimalized doctrines which are not related.

Let me give you a couple of examples of how I use this schema. The first one is from St. Thomas Aquinas. It is a well-established fact that St. Thomas tried to reconcile the reason of Aristotle with the revelation contained in the scripture. St. Thomas, however, accepted Aristotle's notion of an everlasting Natura (in Greek, physis) which he tried to square with the biblical belief in creation. This attempt led him to the mixed notion of "sempiternity, " i.e., a world which was "created from eternity." Now this is evidence of a nimble mind, but I would say that St. Thomas lets the Aristotelian notion of nature overtake the doctrine of creation with the result that we would have to write his schema N-R-G. A second example I take from Joachim of Fiore, the medieval millennial theologian. Joachim taught that there were three ages in the schema of salvation. First there was Creation, the Age of the Father, which is now over with; then Redemption, the Age of the Son, and that too is over with; and finally the Age of Sanctification in the Holy Spirit, an age which Joachim and his Franciscan Spiritualist followers thought would arrive in 1260 A.D. Following the schema, I would write Joachimite theology as c/r/G. (My reason for bringing up Joachim is that there are many affinities between Unificationist and Joachimite theology; still, I would say that the Unificationists are not ultimately Joachimites because of their strongly articulated theology of creation and its interconnection with the theology of glorification.)

At this point, I will pick up my earlier line of argument about neo-orthodoxy and the theology of secularization, two theologies which have had immense influence on this country. In my schema Barth's theology reads c-R-g. He funnels the full content of revelation into the second article of the Creed without allowing for the check-and-balance that the earlier Christian fathers felt was necessary between the three articles. In Barth's theology we do not know much about creation because of our corrupted nature. Nor do we know much about glorification because of our paradoxical situation in Christ as simul justi et peccatores, at once justified and sinners. Barth so radicalizes the Lutheran doctrine of justification that he makes no room for the possibility of regeneration. In effect Barth is a christomonist who sees the revelation in Jesus Christ as a new creation, a radical new departure that clouds over the providential intent of God in the original creation.

Now the point I am going to make might seem trivial, but we should not forget that the christological controversies between the Council of Nicaea and the Council of Constantinople raged over the addition or subtraction of a single letter of the Greek alphabet: was Jesus Christ homoousios (of the same being) or homoiousios (of similar being) with the Father? My point is that Paul's famous phrase kaine ktisis (2 Cor 5:17; Gal 6:15) ought to be translated "creation anew" or "creation renewed'' In giving too much weight to the radical otherness of the revelation in Jesus Christ, christomonists seem to be saying that God gave up on the first book (the Old Testament) he was writing and started over with a second one (the New Testament). One gets the impression that dialectical theologians like Barth, Bultmann and Gogarten really think that God had cancelled his copyright on the Book of Creation.

I think that in our time we need to emphasize that God was writing only one book and that creation and gospel are interconnected chapters in that book. (The Unificationists remind us that there is a third chapter, too!) Contrary to what many Heilsgeschichte (salvation history) theologians are saying, I would assert that the providential plan of God for history must be seen in light of the creator of the heavens and the earth" and that creation cannot be subordinated to historical events like the Exodus. If I may refer to the Epistle to which Barth paid so much attention, the revelation in Jesus Christ (in Greek "revelation, " apocalvpsis, means literally "uncovering") was a revelation about something that was already there, namely, the creation. Hence Paul indicts the nations not on the basis of their accepting or rejecting the gospel but on the basis that they "worshipped and served the creature rather than the Creator, who is blessed forever!" (Rm 1:25). And just as Paul sees creation renewed by the revelation in Jesus Christ, so also he relates his eschatology to this same creation, "... has been groaning in travail..." (Rm 8:22). The human, bodily process of conception, pregnancy-labor, and childbirth is an apt metaphor for the way Paul relates creation, redemption and glorification and a key to understanding Paul's reading of the single "divine economy" or schema of salvation.

If we turn our attention to the American liberalism which colors all of our thinking, we discover an even more radical neglect of the doctrine of creation and how it relates to history. For us the creation no longer manifests the revelation of God's will for man but has become instead a kind of "raw material" and "resource" which we shape and transform at will. Furthermore, God's redemptive providence in history has become for us a kind of self-provision through our mastery of technique. Finally, in terms of the traditional Christian Creed, we have abandoned belief in "the Last Things" and substituted in its place a belief in progress which is registered in terms of what is calculable, e.g., the expanding economy, technological innovation, the exploitation of our resources, etc. In the schema I employ, one would have to say that we are secularized economic Joachimites. I would write our transformation of the Creed as c/r/P(rogress).

Yet the American liberal faith in progress has been shaken to the core by the economic, political, ecological and technological crises which have imperiled our future. Typically, the American response in such situations is to return to "Jesus as the only one." Now I for one do not want to put down christocentric evangelicalism or even the charismatic resurgence within the mainline churches. But, theologically speaking, these responses to our situation are second article answers to a first article problem. What is needed is a first article response to problems having to do with our distorted relationship to the created order.

Let me give an example. All of us recognize that we are on the horns of a great dilemma. On the one hand, there is the energy crunch. On the other hand, our means for extracting energy from the earth have led to ecological and social devastation. How did this situation arise? The answer is that we thought we could get progress without paying attention to the laws of creation. We wanted progress without restoration and regeneration of the earth. Our predicament arose precisely at the moment we thought we could separate God from the natural order and twist and torture nature -- the image is from Francis Bacon -- to our own, purely man-centered, purposes. By now it is clear to us that nature is not a passive and neutral "raw material" on which we can realize ourselves in freedom and history. The creation resists our exploitation and violence. In our time we can see nature striking back and revealing to us the laws God embodied in the creation.

It is precisely this view of creation as the active revelation of God's providence that is inaccessible to modern man. And not only does liberal secular theology fall short here, but also Marxist humanism. Marx unwittingly took over the Enlightenment concept of nature as raw material which he opposes to history, the arena in which man "creates" himself. Just as Marx turned Hegel "on his head, " so he inverted the structure of the Creed and put creation in the last place. What gets created is man himself who realizes himself in history by overcoming the material conditions of existence. Marx saw clearly that certain classes could garner the means of production and thereby oppress other classes. Yet in order to overcome the destructive tendencies of class society and bring about "the humanization of nature and the naturalization of man, " Marx was impelled, by the sheer logic of his immanent historicism, to give free reign to applied natural science for the sake of maximizing the means of production. Thus there is no possibility for a critique of technology built into Marxism. The reason for this is that in Marxism there is no original purpose to the creation other than a view of nature as the raw material for human productivity. There is no providence other than man mastering the forces of nature for his satisfaction and enjoyment. Although Marx saw in religion "the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, " religion was nonetheless "the opium of the people" because it numbed humanity into deferring plucking the living flower in favor of the imaginary flowers of an illusory heaven.5 Because he had no vision of the original purpose of creation, Marx was led to reject the notion of providence in history. "Providence, providential purpose." he wrote, "this is a big word used today to explain the movement of history. In actual fact it explains nothing."6 Using the schema, we would have to write Marx's transformation of the creedal formula as n-r-g (nature as raw material, "redemption" as human productivity, "glorification" as the human creation of the classless society).

In this final part of my response I am going to focus on Unification theology. Now while it is easy to see Unification thought as a reaction to Marxism -- and it is that -- it is equally important to relate it to the structure of Christian theology. Again, using the schema I have proposed, we could write Unification theology as C-(r)-G. First, one of the reasons I am excited about Divine Principle is that it restores the doctrine of creation as the first subject theology has to deal with. As I have noted above, modern theology, orthodox and secular, has drawn a blank when it comes to creation, and theologians like Gustav Wingren (cf. Creation and Gospel, New York, 1977) have underscored this deficiency in modern theology.

Not only does Unification have a strong doctrine of creation but also this doctrine is articulated in a creative way. In the Divine Principle God is not primarily conceived as a solitary cause, author or architect but as parent. That is, creation is thought of as a parentage. Not only this. Because the godhead is represented as true parent, i.e., as a being whose very nature is relationship, the creation is represented in a relational way with the Creator. This relational bond articulates a neglected side of the theology of creation: God did not make the universe the way an artisan makes a chair. The artisan can make a chair and forget about it. That is, the artisan's act of making is an ephemeral relation. When parents bring forth offspring, their relation to their offspring does not cease even though children grow up to become parents in their own right. With the image of God as parent, the Divine Principle is able to ward off the tendency in Christian theology to think of creation as an event "back then." Rather, creation is an enduring, sustained relationship between Creator and creation. In the Divine Principle this notion of sustained relationship is treated under the rubric of "give and take" (cf. Divine Principle 1.II.2, pp. 28 ff.).

Professor Richardson has pointed out another creative aspect of the theology of creation in the Divine Principle. It is an aspect to which Roman Catholics can respond with affirmation, for Catholics believe that humans are co-creators with God in parenting. Richardson notes the radical theocentricity of the Unification notion of creation. God did not want mute objects as his image in creation but co-creators.7 Modern notions of human creativity tend to see it as the autonomous self-productivity of individuals, i.e., as non-relational activity. In the Divine Principle, however, human creativity is grounded in the duality of give-and-take vertically between the Creator and the creation, horizontally between humans, and vertically between man and the environment.

A second major feature of Unification theology flows from the principle of creation, namely, the doctrine of glorification as restoration. Here, again, Unification theology picks up a theme of earlier Christian theology that has long been neglected. The early Church fathers believed that the Last Things (eschatology) were intimately related with the First Things (creation). Hence, theologians like Irenaeus saw redemption not as the cancellation of God's claim on an evil material world, which many Gnostics thought was fabricated by an incompetent demiurge, but a restoration and reassertion of the supremacy of goodness in the creation, both spiritual and physical. Traditional Christian theology, in my estimation, needs to recapture this early Christian insight: the material creation is as good as the spiritual creation because both are from the same Creator. For various reasons, Christianity has succumbed to the temptation to rank the spiritual dimension of life above the physical or even claim that the physical is in some way evil in itself, e.g. the extreme "denial of the body" in some forms of asceticism. The important thing is to see the goodness of both and how that goodness flows from the proper relation between the spiritual and physical. Now I think that one of the great insights in the

Divine Principle is that goodness (as illustrated by the three "blessings") is not manifested by the ranking of either the spiritual or the material above one another or in their independent development (religion vs. science) but in their reciprocal co-ordination.

Another way in which the Divine Principle relates the First Things and the Last Things, creation and restoration, is to see the fall not so much as a transgression, incurring a guilt for which a penalty must be paid (the cross), but as the interruption of the process of the blessings. Thus in Unification theology the saving act is the restoration of the creational process of formation, growth and perfection or individual perfection, marriage and dominion over the earth (Divine Principle I.l.v.2, pp. 52-57). In other words, Unification theology is able to uncover the eschatological directionality of God's original intent in the creation. The Divine Principle teaches not so much that Adam and Eve were disobedient when they sinned but immature and weak. Thereby Satan (sin) was able to get a toe-hold on the material world and exert his false dominion.

Before traditional Christians take the Unificationists to task on this theological point, they had better first consider that Paul had the same opinion about Adam and Eve being immature and trickable in the face of Satan's wiles. Paul makes this point in Romans 7:7-11, which is a kind of midrash on Genesis 2-38 Secondly, Paul constantly stresses the restoration of the spiritual growth process in Christ (1 Cor 13:11). Another link between Unification and traditional theology is that it holds to the Calvinist doctrines of our "federal headship in Adam" and of the two sovereignties (God's and Satan's). None of us should overlook the important fact that Rev. Moon's parents converted to Presbyterianism when he was 10 years old.

A final note on Unification eschatology. I think that the Unificationists have been able to regain that sense of eschatological urgency which the early Christians had. I think there is no getting away from the fact that the early Christian expectation of the second coming became deeschatologized and "ontologized" into a cosmic topography ("heaven"). This is the point of Martin Werner's book The Formation of Christian Dogma.9 As the second coming became de-emphasized, I think Christianity lost sight of what Paul calls the oikonomia tou theou, the crucial moves of God in the "economy" of salvation.

Because the second coming was lost sight of, greater emphasis was placed on the first coming and, in particular, on the person and acts of Jesus rather than on the office and mission of the Christ. In other words, Christianity started emphasizing the definitive act of God in the cross and resurrection rather than seeing the cross and resurrection as part of the broader plan of salvation. Paul, for example, sees the definitive turning point in God's plan of salvation beginning with the call of Abraham (Romans 4).

This question about eschatology leads me into the Unificationist handling of the second article of the Creed, and more particularly their christology. I have written their theology of redemption as -(r)-. I am not at all sure this is the right way to do it. But this much can be said: from the perspective of the mainline Christian traditions, they have a low christology. But I would like to point out that mainline Christianity has tended to emphasize the theology of redemption at the expense of creation and glorification. Furthermore, mainline Christianity is also plagued with overweening individualism. It is this excessive individualism, I suggest, which accounts for the stress on the uniqueness and singularity of the person and work of Jesus Christ. This is particularly true (I am going to be unkind!) of certain forms of evangelical Protestantism. Catholics, though they have their problems with it, do realize that there is a third article of the Creed which includes the doctrine of the church and the communio sanctorum. Now I would like to point out that as long as Christians play the individualistic "Jesus-and-Me" game or place everything into a "Decision-for-Christ" (Has anyone noticed that Billy Graham and Rudoph Bultmann are speaking the same language on this point?!), they will not be able to account for the full structure of Christian theology nor will they have any practical answer to Marxism or secularization.

When we look at Unification theology from within, however, I think we can say they have a high christology. Unification, like Calvin, stresses the offices of the Christ. Jesus is prophet, priest and king rather than God-man (though the latter is not denied). Now office christology looks to the whole plan of salvation and providential history, including both Testaments. Secondly, office christology also underscores the fulfillment of the functions of that office. From this perspective, Unification theology would say that Jesus in person completed his mission but that certain functions were left to God's future providence. Was not the early church saying something similar when it felt the need to have a third article in the Creed? In other words, the early church (and Unification) is saying that providential history was not over with sometime around 30 A.D.

A final note on Unification christology. Technically speaking, the Unificationists do not talk about "redemption" but about "indemnification." This follows consistently both from their notion of restoration as a renewal of the process of growth intended in the original creation and from their notion of the messianic office. Professor Richardson is not happy with the word "indemnification" and thinks a word like "sacrifice" would fit better. The word is all right by me. (As an aside, I think a case can be made that the notion of indemnification strikes a mediate position between the classic Catholic notion of meritum de condigno and the Protestant notion of justification by faith alone. This point deserves a separate discussion.) What I would like to indicate in this context is that the word "redemption" speaks to a single act whereas "indemnification" speaks to the process of compensation for what was lost in the fall.

Now that I have spent so much space interpreting (and defending!) Unification, I will end with three "negative" notes of caution. Sometimes the Unificationists talk substance language and sometimes they talk process language. Now if one is going to use substance language, one has to pay the indemnity (!) for the whole weight of the Western philosophical tradition stemming from the Greeks. In substance language, isolated individual objects have being in the full sense while relations are held subordinate. I have already pointed out how Greek "nature" terms got St. Thomas Aquinas into trouble, and I think the Divine Principle (as opposed to the doctrine of the principle) generates some needless entanglements by not carefully distinguishing these two modes of speech. Relations like "give-and-take" and processes like formation, growth and perfection get short-shrifted in substance language. A second critique I would like to give is that Unification theology is going to have to give some weighty attention to the notion of ineradicable evil if it is not to seem Pollyannish toward the perils of the present. I am not saying that they can give no account, but if they truly want to unify the Christian traditions, they must give a thorough account to other Christian churches which hold to this teaching.

A final critique. There is no critique of science and technology in the Divine Principle. I think there needs to be a distinction between a false domination of the created order and a true dominion in which man is in a give-and-take relation with the material world. They can do this on the basis of their own theology. Science deals with the physical world and we all know that the archangel made his first move on the physical level.

One thing I am grateful to Unification theology for is the way in which it provides a practical, heartfelt motive for the love of the creation. Only such a love, I think, provides the proper framework for sensing God's providence in history. It is because the Divine Principle begins with creation that it is able to articulate an authentic theology of history as restoration. Others might disagree as to the interpretation of this detail or that, but I do not think anyone would deny that the Divine Principle's view of history is theological. Such a grand view of providence in history as a dialectic between man-centeredness (the Cain type) and God-centeredness (the Abel type) has not been seen since the anonymous artisans depicted the great themes of creation, fall, redemption and glorification on the porticos and windows of the medieval cathedral.

As a philosopher of religion and culture concerned with religious and cultural symbol systems, I am interested in the Moon movement as a new linguistic community -- "language" being here understood in a broad enough way to include signs and symbols, gestures and rituals. As with any new wedding of language, the language of the Moon movement contains -- like the proverbial bride's attire -- "something old, something new, something borrowed and (perhaps) something blue, " though the latter remains a matter of conjecture. I am only interested in seeing what is old and what is new about this new linguistic community. I will leave it to others to discover what is borrowed and what if anything is blue!

In accordance with my assignment to respond to Mr. Tully's lectures in "providential history, " I will focus attention on the way language is used in the Moonist interpretation of scriptures and history. Given my own interests, it will not be surprising that I will not explore Mr. Tully's specific constructions on "providential history" from the standpoint of some normative orthodoxy, either personal or communal. Nor does time permit questions or comments about how specific linguistic markers seem to be functioning within Unification theology. Rather, I want to make some observations about how language is used as a whole in the Moon movement by taking this interpretation of scriptures and of history as a particularly revealing example of that use.

One further introductory comment and then I can proceed to the task. My characterization of how language is used in Unification theology will take the form of a comparison. I want to indicate the precise points at which modern linguistic usage finds difficulty in the way language is used in the Unificationist interpretation of scripture and history. By implication, I will thereby indicate the kind of metalinguistic shifts that would have to be made for Unification thought to "connect" with the operative use of language in modernity. In one sense, this comparison may be an exercise infutility. Is not the "glory" of the Moonists their "reversal" or "refusal" of modernity? Are there not "pre-moderns" and "post-moderns" aplenty who are quite comfortable with their way of speaking if not always with what they say? Perhaps so! I have heard enough comments from a variety of corners this week to gather that many here are only too happy to leave the moderns to their epistemological quandaries and existential anxieties. Yet modernity cannot be so easily dismissed -- even in the Virgin Islands! There are moderns to be dealt with on the streets, in the academy, in the churches -- even here at this conference. Besides, the Moon movement does strike up "dialogues" with an interesting variety of conversation partners, as this seminar so clearly attests. Therefore, seeking to show how and why Moonism and modernism belong to entirely different universes of discourse -- even and especially when the words used are the same -- is worth one response at this meeting.