![]()

The Words of the Kaufmann Family

|

|

The Words of the Kaufmann Family |

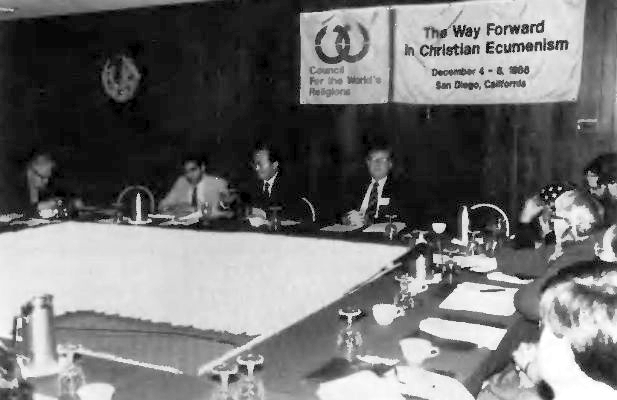

Participants

at the infra-Christian dialogue in San Diego meet with Rev. Kwak.

Religious dialogue is taking place under the Council for the World's Religions (CWR) in ways that are occurring nowhere else in the world. The Council is structured so that religious believers have the opportunity to encounter one another in unprecedented ways. The participants are committed believers who represent specific faiths and organizations. However, in the CWR conferences they are not bound by their positions when they speak but converse with one another in an atmosphere of complete freedom.

The only stipulation in the dialogues themselves is that all dialogue partners be treated with dignity and respect. No agenda is imposed on the participants. The dialogues are not formulated as a means to produce some publicizable evidence, for example, that church X and church Y now agree to worship together in these countries on these Sundays, or any other such resolution. The participants speak freely, openly, and honestly, and for this reason, insights into the real nature of those things that divide religions, and those that might lead to resolution of these differences, are finally becoming clear.

Participants invariably leave the conferences refreshed, enriched, and with the understanding that the ecumenical ideal is no longer a petrified exercise in posturing and beating each other over the head with one's own religious beliefs and doctrines. There is only one purpose for the activities of the CWR: world peace through religious dialogue and harmony. The conferences are designed to pursue that ideal, and to remain open to the unexpected. In dialogue we discover how God is able to bring us together. We do not go into dialogue to tell others how God is obliged to act or how the others are obliged to follow.

Over 20 leaders, scholars, and representatives of the world's major religions are currently advising CWR on how to pursue this one central aim and goal. The Council sponsors several types of conferences toward this end and supports a publishing program to disseminate information and developments in the world of interfaith relations.

Articles have already appeared describing the inter-religious dialogue for the Indian subcontinent held in Bangalore, India, in June 1986, and the gathering of interfaith leaders in Bad Nauheim, West Germany, in August 1986. But these were only two of the CWR conferences held around the globe in 1986. This article will not be able to give a complete description of last year's dialogues, but perhaps a point or two on each would be interesting.

Dr.

Richard Quebedeaux (far left) makes a comment at the San Diego

conference.

The intra-Buddhist dialogue that took place in Chaing Mai, Thailand, brought together Buddhists from eight countries and many denominations. The major and most commonly known division within Buddhism is between the Theravadin and Mahayanan traditions (although there are many more Buddhist denominations). In this conference, even people who have long regarded themselves as Buddhist experts were startled to find that they still operated with certain prejudices and misunderstandings regarding other Buddhist traditions. It was decided there to pursue the idea of an intra-Buddhist translation society, so that Buddhists who speak different mother tongues can begin to understand the roots of one another's faith.

The intra-Jewish conference, held in Vitznau, Switzerland, drew participants from the most distant ends of the spectrum of Jewish belief -- from a Hassidic rabbi who brought his own food (to guarantee it would be kosher), to the most liberal Jewish scholars in American universities. The differences are vast and intense, and at times they seem insuperable. But the oneness grounded in the historical consciousness and experience of all Jews is as unbreakable as the divisions are strong.

The Hindu conference this year, held in the sacred city of Varanasi on the banks of the Ganges River, was on the topic of "Bhakti" (roughly translated as devotion). In this conference, believers in Hinduism (in some ways, the world's most happily divided religion) sought their oneness in the experience of loving and being devoted to God. By whatever name and with whatever nature or quality He was worshiped was secondary to them. Unity was sought in the experience of devotion itself and the loving response of God.

Finally, in December in San Diego, an intra-Christian dialogue was held. Historically speaking, ecumenism in Christianity is perhaps the most sophisticated. Jesus told his followers to be one, and although the followers of Christ have been sorely divided, they have never been comfortable with that fact. For this reason Christianity has the longest and most highly developed ecumenical tradition. It would seem that this is the one area of dialogue in which CWR would be most presumptuous to think it has anything new to offer. Yet the very opposite seems to be the case. Christian ecumenism, in the eyes of many of its most renowned advocates, has reached an impasse, a dead end. Some who have committed their lives to this ideal have actually shed tears of thankfulness to Father for breathing new life and new hope into the field of Christian ecumenism. In San Diego even more lines of division within Christianity were discovered. The participants could recognize that a new approach and a new understanding of the nature of Christian division must first be grasped if progress is to be made.

At all CWR conferences, Rev. C. H. Kwak gives an address to the conferees. It is during this time that participants are able to glimpse the broad and embracing vision of Father and the Unification movement.